Joe Strummer was annoyed. Seriously annoyed.

The year was 1982, and The Clash were deep into the recording of their fifth album, Combat Rock. Bernie Rhodes, the band’s infamous manager, had been complaining that their new tracks were running too long. He reportedly barked at them, "Does everything have to be as long as a gospel hymn?" In a fit of creative spite, Strummer went back to his typewriter. He wanted to write something punchy. He wanted to write words to rock the casbah, but he didn't realize he was about to create the only Top 10 hit the "Only Band That Matters" would ever have in America.

People scream those lyrics in dive bars every Saturday night without having a clue what they actually mean. It’s not just a song about a party. It’s a satirical, jagged piece of political commentary wrapped in a disco-funk beat that drummer Topper Headon actually wrote while sitting alone at a piano.

The True Origin of Words to Rock the Casbah

The phrase didn't come from a Middle Eastern travelogue. It came from a locker room.

The Clash were in the middle of a grueling schedule, and the tension was thick. Topper Headon had laid down a brilliant multi-instrumental track—piano, drums, and bass—but it had no lyrics. Strummer looked at the "gospel hymn" critique and decided to flip the script. He started thinking about the Iranian Revolution of 1979 and the subsequent ban on Western music. Specifically, he’d heard reports of people being lashed for owning disco records or jazz tapes.

That sparked the image of a King (the Sharif) banning "that crazy casbah sound."

Strummer’s genius lay in his ability to mix high-stakes geopolitics with absolute nonsense. He threw in references to "the Bedouin," "the Sheikh," and "the oil refinery" to ground the song in the desert heat. But the core of the song is rebellion. It’s about the fact that no matter how much a government tries to suppress culture, people will find a way to dance. The words to rock the casbah are essentially an anthem for the irrepressible nature of human joy.

Honestly, the irony is thick here. A song about the ban on music became a global dance floor staple. Strummer later admitted he felt a bit weird about how "pro-Western" some people interpreted the lyrics, especially when US pilots during the Gulf War reportedly scrawled the song title on bombs. That wasn't the point. At all.

Decoding the Lyrics: What is a Sharif Anyway?

The first verse introduces the Sharif, who is basically the "fun police" in this narrative.

✨ Don't miss: Who was the voice of Yoda? The real story behind the Jedi Master

The Sharif don't like it.

Rockin' the Casbah.

Rock the Casbah.

In Islamic tradition, a Sharif is a descendant of the Prophet Muhammad, often holding a position of leadership or prestige. Strummer uses the title to represent any authoritarian figure who wants to keep the status quo quiet and orderly. The King calls up his jet fighters to bomb the people who are dancing, but the pilots ignore his orders. Instead, they tune their cockpit radios to the forbidden frequency and join in the groove.

That "Kosher" Line

There’s a weirdly specific line in the song: "He thinks it's not quite kosher."

It’s a bizarre choice for a song set in an Arab context. Some critics at the time thought it was a lyrical stumble, but Strummer was an expert at "kitchen sink" songwriting. He pulled from every cultural lexicon he knew. By using a Jewish term like "kosher" to describe an Islamic ruler’s disapproval, he was highlighting the absurdity of religious and cultural barriers. It was a subtle nod to the fact that, underneath the politics, everyone is just reacting to the same human impulses.

The Bedouin and the Electric Guitar

The imagery of the Bedouin putting down their traditional lifestyles to embrace the "new sound" is the heart of the second verse.

Strummer writes about them ditching their camels for "Cadillacs" (a classic Clash trope—they loved American car imagery). It’s a collision of the ancient and the modern. You’ve got the desert nomads plugged into the global zeitgeist. It’s messy. It’s loud. It’s exactly what punk rock was supposed to be, even if it sounded like a dance track.

Why the Music Video Changed Everything

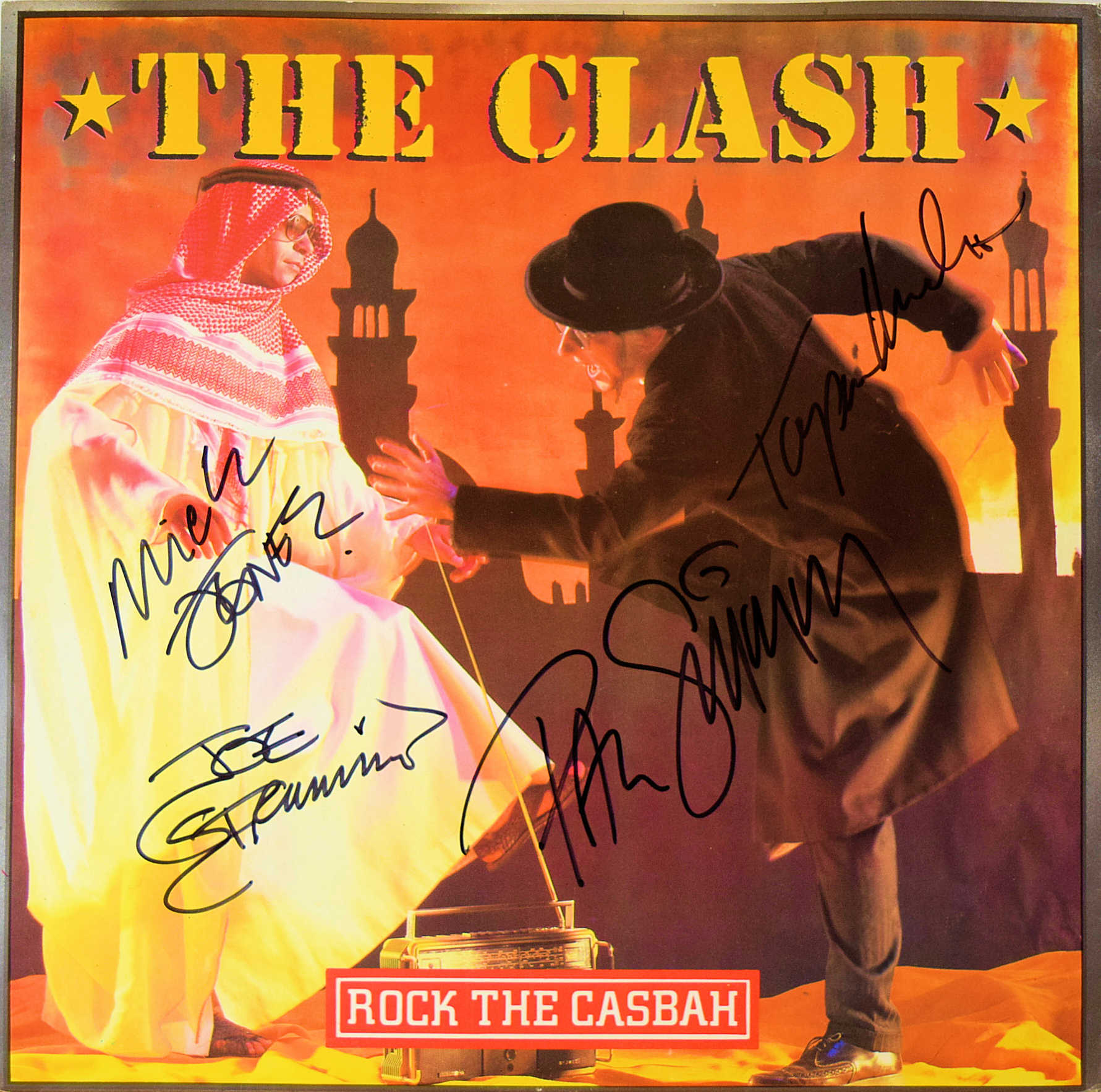

If you grew up in the MTV era, you remember the video. It features a character dressed as an Arab sheikh and another as a Hasidic Jew wandering through Texas together. They’re eating burgers, drinking sodas, and eventually dancing at a Clash concert.

It was filmed in Austin, Texas, which is about as far from a North African casbah as you can get.

🔗 Read more: Not the Nine O'Clock News: Why the Satirical Giant Still Matters

Director Don Letts, a long-time collaborator with the band, wanted to emphasize the "on the road" feeling of the band’s 1982 tour. But the video also added a layer of unintended comedy. You see a lonely armadillo wandering by an oil well. You see the band performing in front of a pumpjack. It’s a visual representation of the song's themes: oil, power, and the weird ways cultures bleed into each other.

Topper Headon isn't in the video. By the time they filmed it, his heroin addiction had led to him being kicked out of the band. Terry Chimes, the band’s original drummer, filled in for the shoot. It’s a bittersweet reality. The man who wrote the melody—the guy who literally played almost every instrument on the studio recording—wasn't there to celebrate its visual peak.

The Musical Structure: Piano and Punk

The song is an anomaly in The Clash's discography.

Most of their songs started with Mick Jones’s guitar riffs or Strummer’s lyrical fragments. This one started with the piano. Topper Headon was a jazz-trained drummer, and his sense of swing is what makes the song work. If you listen closely to the bassline, it’s incredibly busy and melodic. It’s not a standard three-chord punk chug.

- The tempo is roughly 126 BPM, perfect for clubs.

- The use of the "Wha-wha" guitar effect gives it a funk edge.

- The handclaps in the chorus provide a communal, "street party" vibe.

Mick Jones added the sound effects of the jet engines and the "electronic" chirps that pepper the track. These were high-tech sounds for 1982. They gave the song a futuristic, urgent feel that helped it cut through the radio noise of the time.

Misinterpretations and the "Will Rogers" Incident

One of the most famous legends surrounding the song involves a misunderstanding of the lyric "The King called up his jet fighters."

During the 1991 Gulf War, the song became a weird sort of anthem for American troops. It was the first song played on Armed Forces Radio as the bombing of Iraq began. Joe Strummer was reportedly devastated by this. He wept when he heard about it. For a man who spent his life writing anti-war, anti-imperialist anthems, seeing his words to rock the casbah used as a literal soundtrack to a desert war was a gut punch.

It highlights the danger of "vibe-based" listening. People hear the catchy chorus and the Middle Eastern references and assume it's a "Team West" anthem. In reality, the song is about the pilots refusing to follow orders. It’s about the soldiers choosing music over murder.

💡 You might also like: New Movies in Theatre: What Most People Get Wrong About This Month's Picks

How to Use These Concepts Today

If you're a writer, a musician, or just someone interested in cultural history, there are a few things to take away from the way The Clash handled this track.

First, don't be afraid of the "wrong" influence. Topper Headon’s piano part didn't "fit" The Clash's brand at the time. It was too poppy. Too clean. But they leaned into it anyway. Second, use specific details. Strummer didn't just say "the king was mad." He talked about "the degustation" and "the radiator." Those specific, crunchy words make the world of the song feel lived-in.

Third, remember that meaning is fluid. You can write a song about Iranian censorship, and ten years later, people will be using it to celebrate a military campaign you hate. You can't control how the world hears your words. All you can do is make sure the words are worth hearing.

Actionable Insights for Content and Culture

- Embrace Cross-Pollination: The Clash succeeded because they stopped trying to be a "punk" band and started being a "music" band. Don't pigeonhole your creative output.

- Context Matters: Before using a historic or cultural reference, dig into the "why." Strummer’s use of the word "casbah" (a citadel or fortress) was a deliberate choice to show where power is held.

- Listen to the Rhythm: Even if you’re writing prose, there’s a cadence to great work. Vary your sentence lengths. Some short. Some very, very long and winding like a desert road. It keeps the reader engaged.

- Question the Narrative: When you hear a popular song, look up the lyrics. You'll often find that the "party hit" is actually a protest song in disguise.

The Clash eventually imploded under the weight of their own success and internal tensions. Combat Rock was the beginning of the end. But in those four minutes of "Rock the Casbah," they managed to capture a lightning bolt. They took global politics, a manager's annoying comment, and a drummer's lonely piano riff and turned them into something that still resonates decades later.

Next time you hear that opening drum fill, remember: you're not just listening to a hit. You're listening to a story about the inevitable failure of anyone who tries to stop the music. The Sharif never stands a chance.

Source Reference Checklist:

- Redemption Song: The Ballad of Joe Strummer by Chris Salewicz.

- The Clash: Westway to the World (Documentary).

- Combat Rock original liner notes and recording logs (1982).

- Interviews with Don Letts regarding the filming of the music video in Austin, TX.

- Historical archives of Armed Forces Radio (1991 Gulf War broadcasts).

To dig deeper into the actual craft of the song, look up the isolated stems of Topper Headon’s drum and piano tracks. It's a masterclass in independent limb coordination and rhythmic pocket. You can see how the song was built from the ground up, layer by layer, until it became the powerhouse we know today.