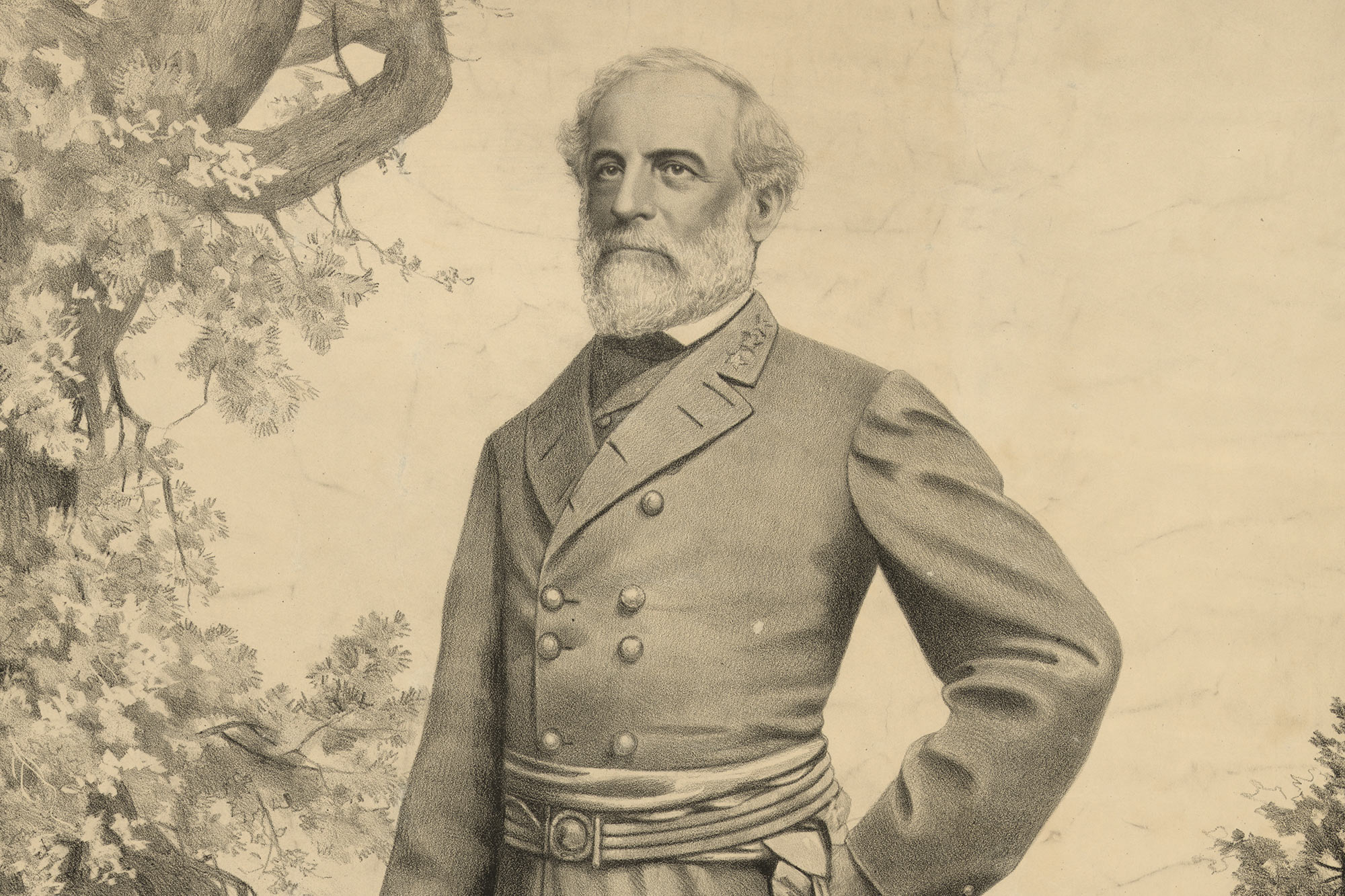

You’ve seen it. That grainy, sepia-toned Robert E. Lee picture where he’s sitting on his back porch in Richmond, looking like he’s got the weight of the entire world on his shoulders. He’s wearing his uniform—the same one he wore to surrender at Appomattox—and he looks exhausted.

Honestly, he was.

It was April 1865. The war was basically over. Lee had just ridden back to his family’s temporary home on Franklin Street. He probably just wanted to sleep for a week. Instead, Mathew Brady, the most famous photographer of the era, showed up at his door.

📖 Related: Traffic 405 Los Angeles: Why the Sepulveda Pass is Still a Nightmare

The Story Behind the Most Famous Robert E. Lee Picture

Brady was persistent. He knew that a photo of the defeated Confederate general would be historical gold. Lee, who wasn’t exactly a fan of the spotlight, initially said no.

It took some convincing. Mrs. Lee and a former staff officer eventually talked him into it.

On Easter Sunday, 1865, Lee stepped out onto the porch. He put on his gray coat one more time. He didn’t smile. In the world of 19th-century photography, you didn't really smile anyway because the exposure times were so long, but this was different.

The resulting Robert E. Lee picture is haunting.

If you look closely at the high-resolution versions, you can see the wear and tear. His eyes aren’t looking at the camera; they’re looking through it. It wasn't just a portrait. It was the visual end of an era.

Why We Are Still Talking About These Images

Photography in the 1860s was a messy, chemical-heavy process. You had glass plates, silver nitrate, and a whole lot of room for error. Yet, the images of Lee that survived are remarkably crisp.

Why do they matter today?

For a long time, these photos were used to build a specific narrative. After the war, Lee became the face of the "Lost Cause." His image was printed on everything from postcards to memorial lithographs.

The bearded, grandfatherly version of Lee we see in most photos—taken by Julian Vannerson or Michael Miley—helped cement that "gentleman general" image. It’s a version of history that has been heavily scrutinized and debated in recent years.

Historians like Donald Hopkins, who wrote a massive book on Lee’s photographic history, have identified about 61 "from life" photographs. That’s a lot for someone who claimed to dislike the process.

Not Just the Gray Uniform

Most people only recognize the Robert E. Lee picture from the war years. But there’s a whole series of him in civilian clothes.

After the war, Lee became the president of Washington College (now Washington and Lee University). He traded the sword for a textbook. The photos from this period show a man who looks significantly older than his actual age.

- 1845: A rare daguerreotype shows a young, dark-haired Lee with his son. (Though some historians argue it's actually his brother, Sydney.)

- 1864: The Vannerson portraits. These are the "iconic" ones where he looks stern and regal.

- 1870: The final photos. Taken by Boude and Miley in Lexington, just months before he died of a stroke.

In that last 1870 session, Lee was actually sitting for a sculptor named Edward Valentine. He looked frail. The "invincible" general was gone, replaced by a tired college administrator.

The Technical Side: How They Were Made

Back then, you couldn't just snap a selfie.

Photographers used the wet-plate collodion process. They had to coat a glass plate with chemicals, rush it into the camera while it was still wet, take the shot, and develop it immediately.

If you were a general in the field, this meant a mobile darkroom wagon had to follow you around.

When you look at a Robert E. Lee picture, you’re seeing a miracle of chemistry. The "Imperial" size prints were huge and expensive. They weren't just snapshots; they were investments in a person's legacy.

The Myth vs. The Man

There’s a lot of baggage attached to these images.

In the early 20th century, these pictures were often used to scrub away the reality of slavery and the brutality of the war. They focused on his "honor" and "dignity."

Today, we look at them differently. We see a man who made a choice to lead an army against his own government to protect a system built on chattel slavery. The photos haven't changed, but our perspective has.

Seeing Lee in high definition makes him real. He isn't a statue or a myth. He's a guy in a suit or a uniform who lived through the bloodiest period in American history.

What to Look For in an Authentic Print

If you’re a history buff or a collector, identifying a real Robert E. Lee picture is a bit of a rabbit hole.

- Check the Back: Real "carte-de-visite" (CDV) photos often have the photographer’s backstamp. Look for names like "M.B. Brady" or "Boude & Miley."

- The Signature: Many prints have a signature. Be careful. Most of these are "facsimile" signatures printed onto the card. Actual hand-signed Lee photos are worth a small fortune.

- The Texture: 19th-century albumen prints have a slight sheen and a very specific sepia tone that modern filters can’t quite replicate.

The Library of Congress holds some of the best original glass negatives. If you want to see the "real" Lee without the filters of time, that's where you go.

Actionable Insights for History Enthusiasts

If you want to dive deeper into the visual history of the Civil War, don't just look at the faces. Look at the background.

In the 1865 Brady photos of Lee, the porch is bare. The house is quiet. It tells you as much about the state of Richmond as Lee's expression does.

To truly understand a Robert E. Lee picture, you have to look at the context of when it was taken.

- Visit the National Portrait Gallery website to see high-res scans of the Brady collection.

- Compare the 1863 "uniformed" photos with the 1869 "civilian" photos to see the physical toll of the war.

- Research the photographers themselves; men like Michael Miley were pioneers who stayed with Lee until the very end.

Understanding these images isn't about glorifying the past. It’s about seeing it clearly. When you strip away the legends, you’re left with the raw, chemical evidence of a man who shaped, and was shaped by, a divided nation.

Start by examining the 1865 "Back Porch" series. It’s the most honest look you’ll ever get at a man who knew he had lost everything.