You’ve heard the story. Everyone has. It’s one of those "creepy" facts people love to drop at parties or post on TikTok for easy engagement. The story goes that "Ring Around the Rosie" isn’t just a cute playground game, but a morbid oral history of the Great Plague of London in 1665. The "rosie" is the red rash. The "posies" are the herbs people carried to ward off the smell of death. "Ashes, ashes" refers to cremation. "We all fall down" means, well, everyone dies.

It’s dark. It’s spooky. It’s also almost certainly total nonsense.

If you’re looking for the real origin of nursery rhyme ring around the rosie, you have to look past the urban legends and into the messy, often boring world of 19th-century folklore studies. Folklore doesn't usually come from a single traumatic event. It evolves. It drifts. It changes shape based on who is singing it and where they are standing.

The Plague Myth: A Case of Modern Back-Formation

The Great Plague theory didn't actually show up until after World War II. Think about that for a second. If the rhyme was really about the 1665 Black Death, why did it take nearly 300 years for anyone to notice?

Folklorists like Iona and Peter Opie, who basically wrote the bible on children's games (The Singing Game), did a deep dive into this. They found that the "plague" interpretation only really started gaining traction in the late 1940s and 50s. Before that? Nobody made the connection. Not the Victorians, not the Georgians, and definitely not the people living through the plague itself.

The "ashes, ashes" line is a huge red flag. In the oldest versions of the rhyme, that line doesn't even exist. Instead, kids sang "A-tishoo, A-tishoo" or "Husha, husha." It was an imitation of a sneeze, not a reference to burning bodies. Also, historically speaking, the English didn't typically cremate plague victims in the 1600s; they buried them in mass pits. The "ashes" bit is likely an Americanization that gained popularity much later.

📖 Related: Bridal Hairstyles Long Hair: What Most People Get Wrong About Your Wedding Day Look

What the Earliest Versions Actually Look Like

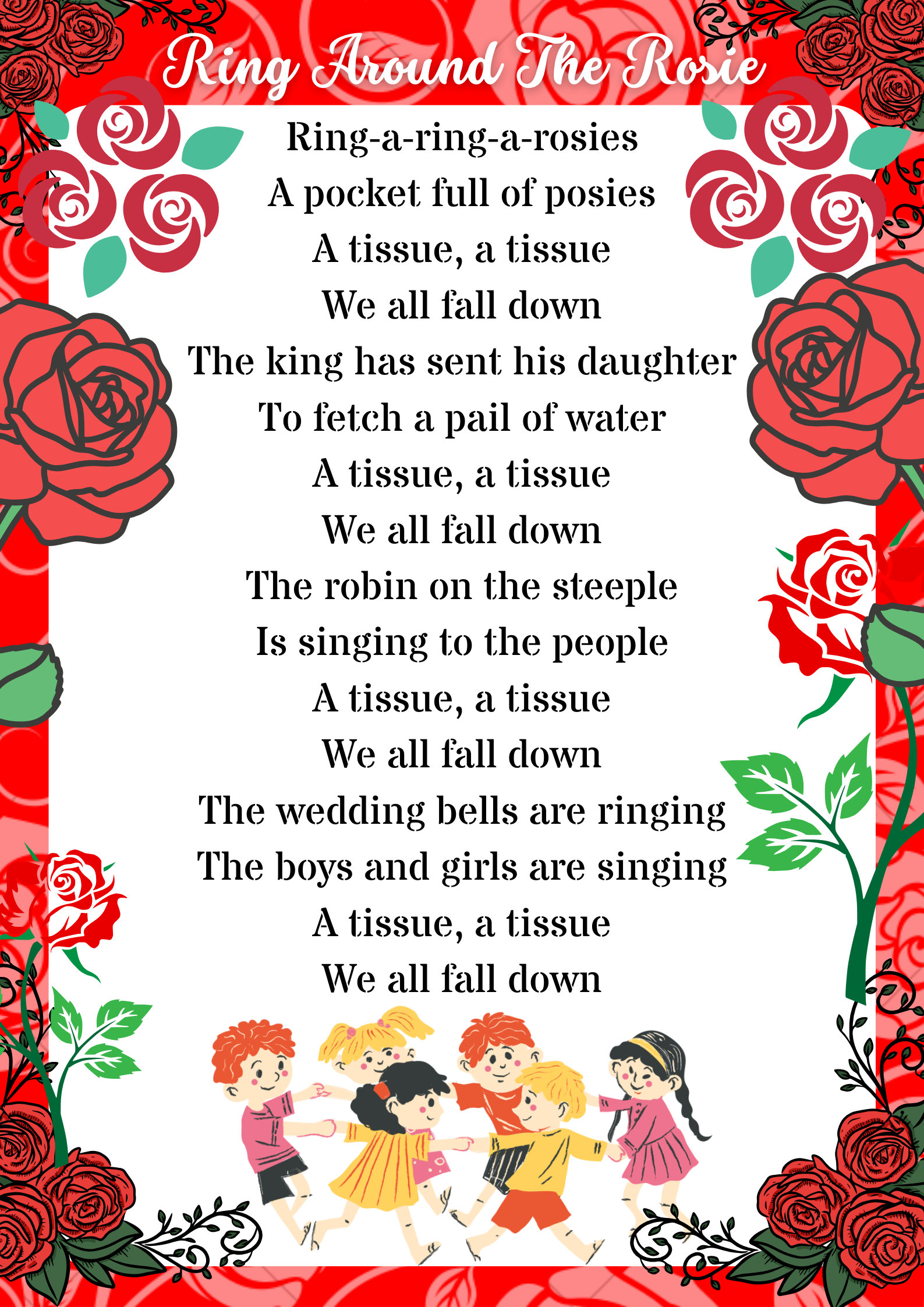

The first time this rhyme actually shows up in print is around 1881 in Kate Greenaway’s Mother Goose. But even then, the lyrics were all over the place. In some versions from the mid-1800s, the lyrics mention wedding bells or bird sounds.

Check out this version from 1883 in Shropshire:

"A ring, a ring o' roses,

A pocket full o' posies;

One for Jack and one for Jim

And one for little Moses!

A-tishoo! A-tishoo! All fall down."

Hardly sounds like a death march, right? It sounds like a bunch of kids making up nonsense to rhyme with "roses." The "posies" weren't medical supplies—they were just flowers. Flowers have always been a staple of children's games. You make a ring, you pick some flowers, you fall down. It's simple.

Actually, the "falling down" part is common in hundreds of European circle games. It’s the payoff. Kids love the physical release of tumbling to the ground. It’s the same reason "London Bridge is Falling Down" is popular. It’s about the sudden movement, not a structural engineering disaster or a Viking attack.

Why We Want it to be About Death

We’re obsessed with the "secret" meanings of things. There is something satisfying about finding out that a "wholesome" childhood memory is actually rooted in a historical horror show. It feels like we’ve cracked a code.

👉 See also: Boynton Beach Boat Parade: What You Actually Need to Know Before You Go

But folklorist Philip Hiscock argues that this is just a case of "metafolklore"—folklore about folklore. We love the plague story because it makes the rhyme more interesting. It gives it stakes. But if you look at the 19th-century German, Swiss, or French versions of the game, they all involve different variations of skipping, dancing, and bowing. The "rosie" was often a reference to the "Rose" (the girl in the center of the circle) or simply the shape of the ring itself.

The Evolution of the Lyrics

The rhyme changed depending on where you lived. In some parts of the U.S., it was "Ring-a-ring-a-rosie, a bottle full of posie." In others, the "all fall down" part was replaced by a "curtsy" or a "bow."

- 1881 (England): "A ring, a ring o' roses / A pocket full o' posies / Hush! hush! hush! hush! / We're all tumbled down."

- 1848 (Massachusetts): Mentioned as a "social game" played by young people (not just kids), often as a "play-party" game where dancing was forbidden by the church.

- 1910 (Germany): "Ringel, Ringel, Reihe" (Ring, ring, row).

The diversity of the lyrics is the strongest evidence against the plague theory. If it were a specific historical record of a specific epidemic, the core elements would be more consistent across time. Instead, we see a "linguistic drift" where the sounds matter more than the meaning. "Hush" becomes "A-tishoo" which becomes "Ashes."

The Religious and Social Context

In the 1800s, many religious communities in the United States banned "dancing." It was seen as sinful. To get around this, young adults created "play-parties." These were basically dances where people sang instead of using instruments and followed "game" rules instead of "dance" rules.

"Ring Around the Rosie" was often one of these games. It was a way for boys and girls to hold hands and move in a circle without getting in trouble with the preacher. The "falling down" was a way to end the round and reset. It was social. It was flirtatious. It was definitely not a funeral rite.

✨ Don't miss: Bootcut Pants for Men: Why the 70s Silhouette is Making a Massive Comeback

Honestly, the plague theory is a bit like those creepypastas about Rugrats or SpongeBob. It’s a modern layer of grimdark paint applied to something old and simple.

Why the Myth Persists

Despite every major folklorist—from the Opies to the experts at the Library of Congress—debunking the plague connection, it won't die. Why? Because the internet loves a "Did You Know?" fact that sounds smart.

Even museums and some history books have accidentally repeated the plague story because it’s so ingrained in our culture now. It’s a perfect example of how a lie can travel halfway around the world while the truth is still putting its shoes on.

How to Evaluate Nursery Rhyme Origins

If you want to know the real story behind a rhyme, look for three things:

- The earliest print date. If it wasn't written down until 200 years after the event it supposedly describes, be skeptical.

- Regional variations. If every country has a different version, it’s likely a general game, not a specific history.

- The "Opie Factor." Check if Peter and Iona Opie debunked it. They usually did.

The origin of nursery rhyme ring around the rosie is a testament to how children’s play survives through centuries of oral tradition. It doesn't need a dark secret to be important. It’s a piece of living history, a game played by millions of children who just wanted to spin in a circle and fall on the grass.

To get a real sense of how these traditions work, look into the British Library’s archives on children’s games or pick up a copy of The Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes. You’ll find that the truth—while less "spooky"—is actually much more fascinating because it shows how language evolves through play. Next time someone tells you it's about the plague, you can politely tell them they're about 80 years too late for that theory.

For those interested in exploring further, the next step is to research "play-party" songs of the 19th century. You will find that many songs we consider "scary" today, like "Pop Goes the Weasel," actually have very mundane origins in the London textile industry or social dancing. Focus on primary sources from the 1800s to see how these lyrics looked before modern interpretations took over.