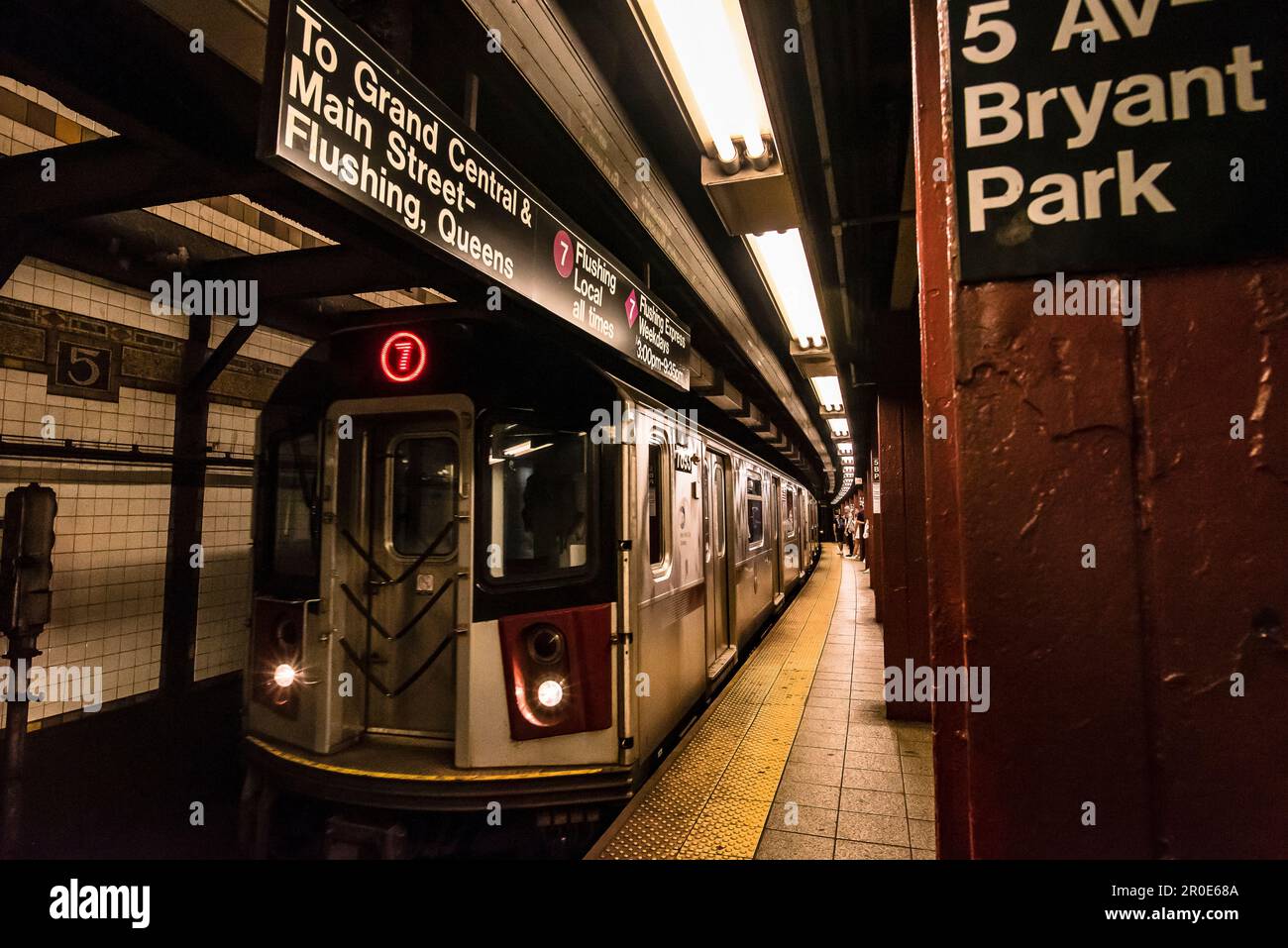

The 7 train is loud. If you’ve ever stood under the elevated tracks at 82nd Street in Jackson Heights when an express train screams past, you know that bone-rattling screech. It’s a sound that defines Queens. Some people call the 7 train the "International Express," and honestly, it’s a bit of a cliché at this point, but it’s the only nickname that actually sticks because it’s true. You start at 34th Street-Hudson Yards, surrounded by shiny glass skyscrapers and high-end shopping, and within thirty minutes, you’re eating the best tacos al pastor of your life under a flickering neon sign in Corona.

The 7 train isn't just a way to get to a Mets game. It is the geographic spine of the most diverse county in the United States.

But here’s the thing: most commuters just see it as a crowded hunk of metal that occasionally breaks down during rush hour. They miss the engineering madness that keeps this line running and the weird, shifting history of why it looks the way it does. From the "Steinway" tunnels that were never meant for trains to the modern-day implementation of Communications-Based Train Control (CBTC), the 7 is a weird mix of 1910s grit and 2020s tech.

Why the 7 Train is Different from Every Other Line

New York’s subway system is basically three different railroads wearing a trench coat. You’ve got the old IRT, the BMT, and the IND. The 7 train belongs to the IRT (Interborough Rapid Transit) family, which means the cars are narrower and shorter than the beefy trains on the A or the Q. If you try to run an A train on the 7 tracks, you’re going to have a very bad day and a lot of scraped concrete.

What really sets it apart is the "Flushing Line" designation. It’s one of the few lines that operates almost entirely as a self-contained ecosystem. It doesn't share tracks with other lines for most of its journey, which is why it can run with such high frequency. On a good day, you’re looking at a train every two to three minutes. That’s insane. Most cities would kill for that kind of headway.

The Extension to 34th Street-Hudson Yards was the first major subway expansion in decades when it opened in 2015. It changed the game. Suddenly, the far West Side wasn't a wasteland of parking lots and rail yards. But let's be real—the deep-bore station there feels like it belongs in London or Moscow. It’s so deep you could practically hide from a nuclear blast down there. Walking from the platform to the street feels like a mountain hike.

✨ Don't miss: How Do I Get to LaGuardia Airport Without Losing My Mind

The Chaos of the 7 Express

If you’re a New Yorker, you know the "7 Express" gamble. You see the diamond 7 symbol on the front of the train and you feel a surge of victory. It skips the local stops between 74th Street-Broadway and 33rd Street-Rawson. It feels like flying.

But then, it happens.

The train crawls to a halt somewhere over Sunnyside Yards. The conductor comes over the speaker—usually sounding like he’s talking through a tin can filled with gravel—and mentions "train traffic ahead." This happens because the 7 line uses a single center track for express service. In the morning, it runs toward Manhattan. In the afternoon, it runs toward Queens. It’s a tidal system. If one train in the chain has a mechanical issue or a "passenger move," the whole express line bottlenecks. There’s no passing lane. You’re stuck.

The Real Tech: CBTC and Why It Matters

You might have noticed the 7 train runs smoother than the F or the R. That’s not a fluke. The MTA spent years (and a lot of your tax dollars) installing Communications-Based Train Control.

Basically, the old signals used "blocks." A train couldn't enter a block until the train ahead left it. It was a 100-year-old safety system using colored lights. CBTC is different. It uses digital pings to tell the system exactly where every train is, down to the inch. This allows trains to run closer together. It’s the reason the 7 can handle the absurd surge of people leaving Citi Field after a concert or a Friday night Mets game without the whole system collapsing into a heap of delays.

The International Express isn't Just a Marketing Slogan

If you want to actually see New York, get off at 74th St-Broadway.

Right there, you are at the intersection of the world. You have Little India to the north and a massive Himalayan community to the south. You can get momos, sari fabric, and Colombian empanadas within a 50-foot radius. It’s dizzying. Most tourists stay in Manhattan because they’re scared of the "outer boroughs," but they’re missing the actual soul of the city.

The 7 train provides a literal window into this because so much of it is elevated. Unlike the dark, damp tunnels of the 4/5/6, the 7 gives you a panoramic view of the Manhattan skyline as you cross the Long Island City waterfront. You see the old Pepsi-Cola sign, the creeping gentrification of LIC, and then the industrial grit of the Sunnyside rail yards. It’s a visual history lesson in real-time.

The Steinway Tunnel Secret

A lot of people don’t realize the tunnel the 7 uses to get under the East River wasn't built for the subway. It was originally the Steinway Tunnel, designed in the 1890s for trolley cars. William Steinway (the piano guy) wanted a way to get people from Manhattan to his "company town" in Astoria.

The project was a disaster. There were explosions. People died. The tunnels sat empty and flooded for years until the IRT bought them and retrofitted them for subway cars. That’s why the tunnel is so tight. When you’re in those tubes, there is very little clearance between the train and the wall. It’s cramped, it’s old, and it’s a miracle it works as well as it does.

Living With the 7: The Commuter’s Reality

Gentrification has hit the 7 line hard. Ten years ago, Long Island City was mostly warehouses and a few brave artists. Now, it’s a canyon of luxury glass towers. This has put an immense strain on the Court Square and Queensboro Plaza stations.

If you’re trying to transfer from the G to the 7 at Court Square during peak hours, good luck. You’ll be doing the "moving sidewalk shuffle" with thousands of other people who look like they haven't slept since 2019. The infrastructure is screaming. While the 7 is more reliable than most lines, the sheer volume of humanity it carries every day is staggering.

- Sunnyside: Quieter, more residential, great pubs.

- Woodside: Heavy Irish and Filipino influence. Go here for the best Thai food in the city (specifically Sripraphai).

- Jackson Heights: The heartbeat of the line. Crowded, loud, and smells like roasting meat and diesel.

- Flushing: The end of the line. It’s a second Chinatown that is actually bigger and more intense than the one in Manhattan.

What to Do if You’re Riding the 7 for the First Time

Don't just sit there staring at your phone. Look out the window.

💡 You might also like: How Far Is New Jersey From Florida? What Most People Get Wrong

Seriously.

Between 33rd Street and Queensboro Plaza, the train makes a sharp turn that offers one of the best views of the Chrysler Building and the UN. It’s free. Well, it’s the cost of a swipe, but you get what I mean.

Also, pay attention to the announcements. On the 7, "Express" and "Local" changes can happen on the fly if there's a problem at the 111th Street yard. You don't want to end up at Main Street-Flushing when you were trying to go to a museum in LIC.

How to Navigate the 7 Like a Pro

- Check the Mets Schedule: If the Mets are playing at home, do not take the 7 unless you have to. The trains will be packed with people wearing orange and blue, and they will be loud.

- Use the Front or Back: People tend to clump in the middle of the platform because that’s where the stairs are. Walk to the very end. You’ll usually find a seat, or at least some breathing room.

- The 74th St Transfer: If you need to get to the E, F, M, or R, this is your spot. It’s a massive complex. Just follow the signs and don't stop in the middle of the hallway to check your GPS. You will get run over by a grandmother carrying three bags of groceries.

- Food Crawl: Use the 7 as a food tour. Start at 103rd St-Corona Plaza for street food, hit 74th St for Indian sweets, and finish in Flushing for soup dumplings. It’s the best $2.90 you’ll ever spend.

Actionable Insights for the Savvy Traveler

If you want to master the 7 train, you need to be proactive. Download the MTA TrainTime app—it’s actually good now. It uses the CBTC data to show you exactly where the trains are in real-time.

When the 7 is down (and it happens, usually on weekends for track work), the Q32 or Q60 buses are your best bets, though they are agonizingly slow. Better yet, if you’re in LIC or Hunters Point, look into the NYC Ferry. It’s the same price as a subway ride if you buy a 10-trip pack, and it’s way more relaxing than being shoved into a 7 train car during a heatwave.

The 7 train isn't just transit. It’s a lived experience. It’s the smell of the river, the sight of the Manhattan skyline, and the sound of twenty different languages being spoken in a single subway car. It’s messy and imperfect, but it’s the most authentic New York experience you can get for the price of a fare.

To make the most of your trip, aim for an off-peak ride on a clear day. Sit on the left side of the train if you’re heading into Manhattan. Watch the city reveal itself. That’s the real magic of the Flushing Line. There is nothing else like it in the world.