You probably have the rhythm stuck in your head already. "Ride a cock horse to Banbury Cross, to see a fine lady upon a white horse." It’s a bit of a linguistic earworm. Most of us grew up chanting these lines without ever pausing to wonder what a "cock horse" actually is or why we're heading to a specific market town in Oxfordshire. It sounds simple. It feels like a cute, nonsensical rhyme designed to keep a toddler bouncing on a knee.

But honestly? The history is way weirder than the nursery rhyme suggests.

History isn't a straight line, and nursery rhymes are the ultimate proof of that. They are like a game of telephone played across four centuries. We think we're singing about a lady on a horse, but we might actually be singing about religious iconoclasm, a massive 16th-century PR stunt, or a very specific type of medieval transport that has nothing to do with poultry.

What on earth is a cock horse anyway?

Let’s get the awkward part out of the way first. When people hear "cock horse" today, they usually think of a rocking horse or maybe a hobby horse. You aren't entirely wrong, but you're missing the original mechanical context.

Back in the day—we're talking the 1500s and 1600s—a "cock horse" was actually an extra horse. If you were pulling a heavy carriage up a particularly steep hill, the team you had out front might start to struggle. You’d hire an additional horse to help with the "cock" (the peak) of the hill. It was the equine equivalent of a turbo boost.

However, by the time the rhyme became a nursery staple, the term had evolved. It started referring to a child sitting astride someone's knee or a hobby horse made of wood. Language shifts. It’s messy. Basically, the "cock horse" in the rhyme serves as a double entendre for the physical act of "riding" a parent’s leg while they bounce you up and down. It's a play on the idea of a high-stepping, proud animal.

Who was the Fine Lady?

This is where the conspiracy theories start. If you visit Banbury today, you’ll see a massive bronze statue of a lady on a horse. It was unveiled by Princess Anne in 2005. It’s beautiful, covered in bells and symbols from the rhyme. But who is she supposed to be?

💡 You might also like: Finding the most affordable way to live when everything feels too expensive

Some historians point toward Lady Godiva. There’s a long-standing tradition of Godiva-style processions in English towns, though there’s zero evidence she ever actually did her famous naked ride in Banbury. She’s usually a Coventry girl.

Others suggest it’s Queen Elizabeth I. Legend has it she visited Banbury and saw a large stone cross. This theory is a bit thin on the ground, mostly because Elizabeth was "the fine lady" of almost every rhyme written during her reign. She was the ultimate celebrity. If something cool was happening in England, people assumed the Queen was behind it.

Then there’s the Fiennes family theory. Celia Fiennes was a famous travel writer in the late 17th century. She rode side-saddle across England and wrote a massive journal about it. Her family owned Broughton Castle, which is just a stone's throw from Banbury. Local historians love this one because it’s grounded in actual geography.

The religious connection you didn't see coming

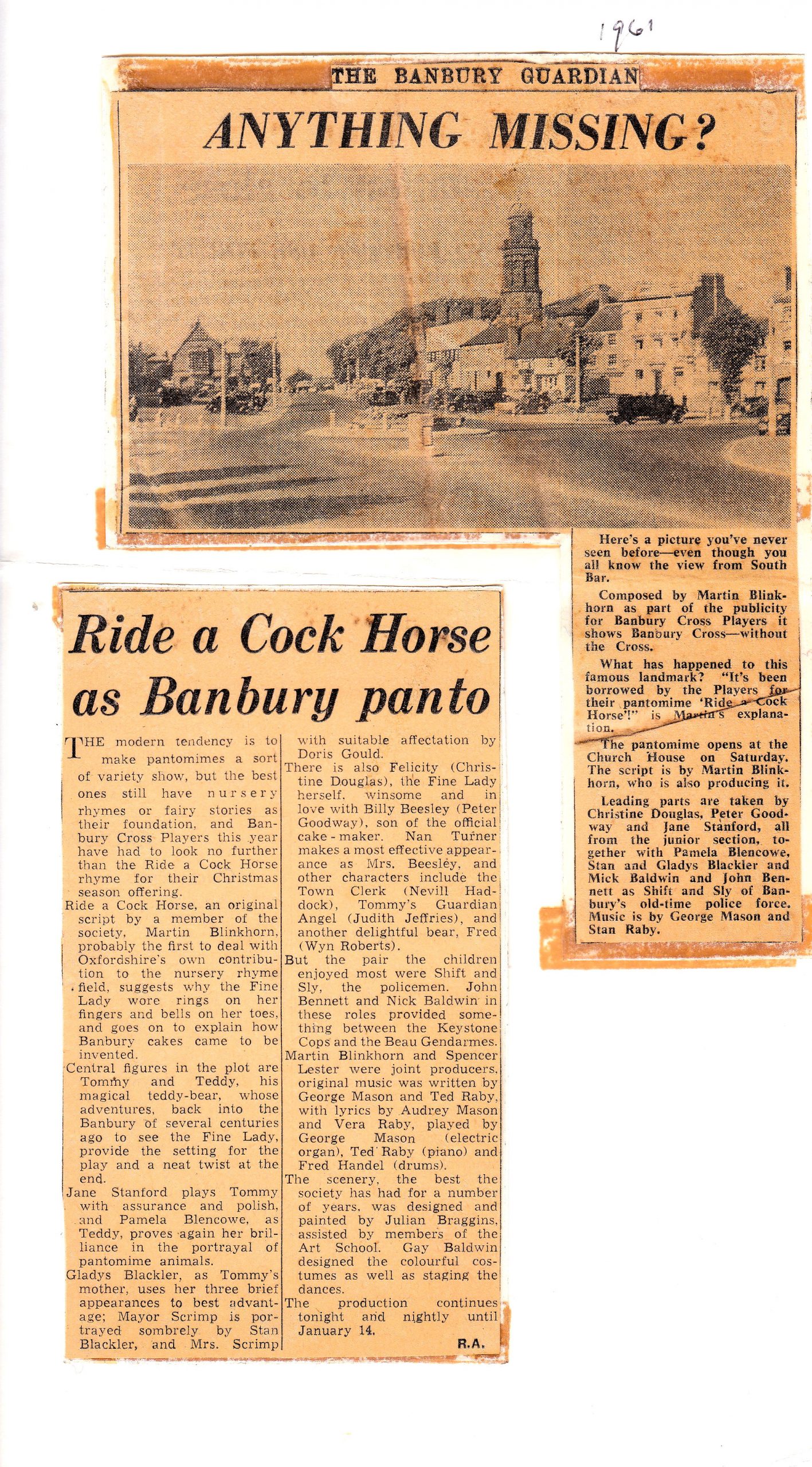

We can't talk about the lady without talking about the Cross. Banbury Cross wasn't just a landmark; it was a symbol of the town's identity. But here’s the kicker: for a long time, there was no cross.

Banbury was a Puritan stronghold. In the late 1500s and early 1600s, the locals were, frankly, quite intense about their religion. They hated "popish" symbols. In 1600, they didn't just ignore the town crosses—they tore them down. They smashed them to bits.

For nearly 250 years, if you went to Banbury to see the cross, you'd be looking at an empty patch of dirt.

📖 Related: Executive desk with drawers: Why your home office setup is probably failing you

This gives the nursery rhyme a bit of a subversive edge. If the rhyme was being sung while the cross was missing, it was a nostalgic nod to a lost landmark. It was a "remember when" in musical form. The current cross you see in the center of town? That’s a Victorian "reboot" built in 1859 to commemorate the marriage of Queen Victoria’s eldest daughter. It’s a beautiful piece of architecture, but it’s essentially a 19th-century tribute to a 16th-century ghost.

Why Banbury?

Banbury wasn't just some random village. It was a bustling market hub. It was famous for two things: its zealot Puritans and its Banbury Cakes.

If you've never had a Banbury Cake, imagine a flatter, spicier, more sophisticated Eccles cake. It’s flaky pastry filled with currants, peel, and a heavy hit of nutmeg and cinnamon. These cakes were so famous they were exported as far as America and India in the 1800s. Ben Jonson, the famous playwright and contemporary of Shakespeare, even wrote about the "Banbury man" who sold these spiced treats.

When the rhyme mentions "rings on her fingers and bells on her toes," it’s painting a picture of immense wealth and sensory overload. It matches the vibe of a wealthy market town at the height of its power. The "fine lady" wasn't just some random traveler; she was a spectacle. She was the 17th-century equivalent of a supercar driving through a small town.

The music and the rhythm

The meter of the rhyme is what makes it stick. It’s a trochaic gallop.

DA-da DA-da DA-da DA-da.

It mimics the sound of hooves. It’s tactile. When you bounce a child on your knee to this rhyme, you aren't just reciting poetry; you are performing a physical history lesson. The "music wherever she goes" likely refers to the bells on the horse’s harness, a common feature for high-status travelers to ensure people moved out of the way. It was the Victorian siren.

👉 See also: Monroe Central High School Ohio: What Local Families Actually Need to Know

Fact-checking the folklore

Let’s be real for a second. Folklore is a mess of half-truths.

- Was there only one cross? No. Banbury actually had several, including the High Cross and the Market Cross. The rhyme likely refers to the main High Cross.

- Is the lady a specific person? Probably not. She’s likely a composite character representing the "grandeur" of the upper class that locals would see passing through a major trade route.

- Does the rhyme have a dark meaning? Some people try to link every nursery rhyme to the Great Plague or some horrific execution. Honestly? There’s no evidence for that here. It’s one of the few rhymes that seems to be genuinely about a parade or a grand arrival.

How to experience Banbury Cross today

If you’re a history nerd or just someone who wants to close the loop on a childhood memory, Banbury is worth a weekend trip. It’s not a museum; it’s a living town that has leaned into its fame.

The first stop is the Banbury Cross itself. It stands at the intersection of West Bar, South Bar, and Horse Fair. It’s a tall, ornate Gothic structure. Take a second to look at the carvings—they represent the "fine lady" and various queens of England.

Then, walk down the street to the Banbury Museum. They have a solid collection of local history that explains the town's Puritan past and why they were so keen on smashing things. They also have a lot of info on the "cock horse" and how the rhyme put the town on the map.

Finally, you have to eat the cake. Go to a local bakery and get a real Banbury Cake. Don’t get the mass-produced ones from a supermarket. You want something with that authentic, tooth-aching spice profile that would have made a 17th-century Puritan blush.

Actionable insights for the history enthusiast

If you want to dig deeper into the world of English folklore and the "Ride a Cock Horse" mystery, here’s how to do it without getting lost in the "fake history" weeds:

- Read "The Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes" by Iona and Peter Opie. They are the gold standard. They spent decades debunking the "every rhyme is about the plague" myths and provide the most accurate dates for when these rhymes first appeared in print (for this one, it's roughly 1744).

- Visit Broughton Castle. Since the Fiennes family is a top contender for the "fine lady" identity, seeing their ancestral home gives you a sense of the scale of wealth we’re talking about. It’s one of the most beautiful moated manor houses in England.

- Check out the statue. The bronze statue on South Bar is full of "Easter eggs." Look for the rings on her fingers and the bells on her toes—the sculptor, Les Johnson, didn't miss a single detail from the rhyme.

- Compare the versions. Different regions in the UK have slight variations of the lyrics. Some mention a "white horse," others just a "horse." Looking at these variations can tell you a lot about how regional dialects preserved (or changed) stories over time.

The reality of "Ride a Cock Horse to Banbury Cross" is a mix of urban planning, religious rebellion, and high-society fashion. It’s a tiny window into an England that was transitioning from the medieval to the modern. Next time you hear it, don’t just think of a rocking horse. Think of a town so stubborn they tore down their own landmarks, only to have a song make those landmarks immortal.