When you think about the first steam train invented, your brain probably jumps straight to George Stephenson. It’s the name we all learned in school. The "Father of Railways." But honestly? That’s not quite the full story. Stephenson was the guy who made the steam locomotive a commercial powerhouse, sure, but he wasn’t the one who actually birthed the idea into the world. That honor goes to a giant of a man named Richard Trevithick, a Cornish engineer with a temper as hot as his boilers and a mind that was decades ahead of his peers.

The year was 1804. Napoleon was busy crowning himself Emperor of France, and back in a gritty corner of Wales, something shifted that would change how humans moved forever.

The Pennydarren Miracle: What Really Happened

Trevithick didn't set out to change the world; he set out to win a bet. Samuel Homfray, the owner of the Penydarren Ironworks, wagered 500 guineas—a massive fortune back then—that Trevithick’s "high-pressure" steam engine could haul ten tons of iron along a tramroad. People thought he was nuts. At the time, James Watt, the undisputed king of steam, had convinced everyone that high-pressure steam was basically a ticking time bomb. Watt famously said that Trevithick deserved a hanging for the dangerous pressures he was playing with.

But Trevithick didn't care. He was a "High-Pressure" man through and through.

🔗 Read more: Why the Bored Ape Yacht Club Logo Still Defines Digital Culture

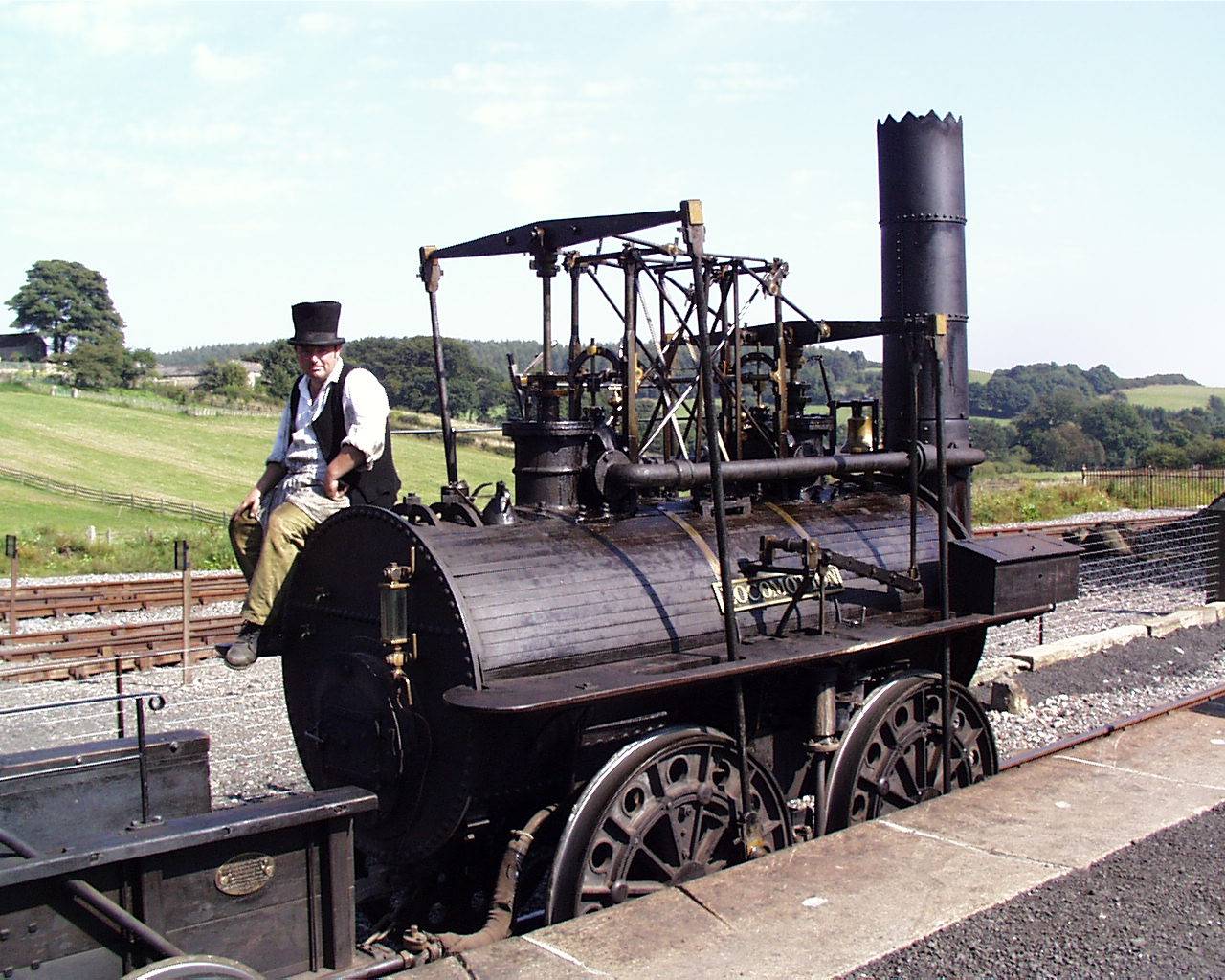

On February 21, 1804, the machine roared to life. It didn't look like the sleek trains you see today. It was a clunky, top-heavy beast with a massive flywheel and a single horizontal cylinder. It puffed. It groaned. It hissed steam like an angry dragon. And then, it moved. It carried 10 tons of iron and 70 men who hitched a ride on the wagons over nine miles of track. It took four hours and five minutes. That’s roughly 2.4 miles per hour. You could walk faster. But speed wasn't the point. The point was that for the first time in human history, a machine was doing the work of dozens of horses without getting tired.

The Problem With the Rails

Here is the thing about that first run: it was technically a failure. Not because of the engine, but because of the ground. The cast-iron rails of the 1800s weren't built for a five-ton locomotive. They were built for horse-drawn carts. As Trevithick’s engine chugged along, the brittle iron snapped under the weight. By the time they finished the journey, the track was a wreck. Homfray won his bet, but the engine was eventually stripped of its wheels and turned into a stationary pump because the "infrastructure"—to use a modern term—just couldn't handle the tech.

Why Trevithick Isn't a Household Name

It’s kinda tragic. Trevithick was a brilliant inventor but a terrible businessman. After the Wales experiment, he tried to show off his tech in London with a "steam circus" called Catch Me Who Can. He built a circular track and charged people a shilling for a ride. But again, the soft ground caused the rails to break, he ran out of money, and he eventually gave up on locomotives entirely to go mine silver in South America. He died penniless in 1833, buried in an unmarked pauper's grave.

Meanwhile, George Stephenson took Trevithick’s high-pressure concepts and refined them. He understood that you couldn't just build a better engine; you had to build a better track. That’s the difference between an inventor and an innovator.

The Tech Behind the First Steam Train Invented

To understand why this mattered, you have to realize what came before. Steam engines existed, but they were huge, building-sized things used to pump water out of mines. They used "low-pressure" steam and a vacuum to move a piston.

Trevithick’s breakthrough was the "strong steam" engine. By using high pressure, he could make the engine small enough to fit on a carriage. No vacuum needed. He also figured out the "steam blast"—exhausting the used steam up the chimney to create a draft that pulled more air into the fire. This made the fire hotter and the engine more powerful. Almost every steam locomotive built for the next 150 years used that exact same principle. It’s the reason trains go "chuff-chuff." That sound is literally the ghost of Trevithick’s genius.

Common Misconceptions About Early Rail

- Myth 1: The Rocket was the first. Nope. Stephenson’s Rocket won the Rainhill Trials in 1829, but that was 25 years after Trevithick’s first run. The Rocket was just the first truly successful, fast, and reliable one.

- Myth 2: Trains were built for passengers. Actually, the first steam train invented was purely for hauling freight—specifically coal and iron. Humans were just an afterthought who hopped on for the novelty.

- Myth 3: Steam was the only option. There were early experiments with "atmospheric" railways and even giant springs, but steam won because coal was cheap and plentiful in Britain.

Basically, the Industrial Revolution was fueled by a desperate need to move heavy stuff from Point A to Point B without killing off every horse in the country. Trevithick provided the spark, even if he didn't get to see the fire spread.

How the World Reacted (They Weren't Fans)

People were legitimately terrified. Farmers thought the smoke would poison the cows. Doctors claimed that traveling at 20 miles per hour would cause the human brain to dissolve or make women’s organs fly out. Seriously. There was a genuine fear that the "iron horse" was a satanic machine.

But the efficiency was undeniable. Once the Stockton and Darlington Railway opened in 1825, using Stephenson’s improved engines, the horse was doomed. The cost of moving goods dropped by 90% in some areas. It was the 19th-century version of the internet—it shrunk the world.

Why This History Matters Today

We’re currently in a similar transition period with electric vehicles and hydrogen power. Looking back at the first steam train invented reminds us that the "first" version of a technology is almost always a "failure" in practical terms. It breaks the rails. It blows up. It goes bankrupt.

But without that awkward, rail-snapping run in 1804, we wouldn't have the global logistics network we rely on today. History favors the people who refine the idea, but we owe a massive debt to the Cornish giant who was brave enough to put fire on wheels and see what happened.

Actionable Insights for History and Tech Buffs

If you want to dive deeper into this era or explore the remnants of the first steam age, here are a few things you can actually do:

✨ Don't miss: ABAT Explained: Why This Battery Tech is Quietly Changing the Grid

- Visit the Science Museum in London: They house the Puffing Billy (1813) and the Rocket (1829). While Trevithick’s 1804 engine doesn't survive, seeing these early beasts gives you a real sense of the scale.

- Explore the Ironbridge Gorge: If you're ever in the UK, go to the birthplace of the Industrial Revolution. You can see the actual terrain and types of tracks that Trevithick struggled with.

- Study High-Pressure Steam: For the DIY types or engineers, look into the "Trevithick Boiler" design. It’s a masterclass in minimalist engineering that still influences small-scale boiler design today.

- Trace the Penydarren Trail: There is a 9-mile trail in South Wales that follows the exact route of that 1804 run. It’s a great hike that puts the physical challenge of early rail into perspective.

Understanding the origin of the steam train isn't just about dates and names. It's about recognizing that every massive leap in technology starts with someone willing to be called "crazy" by the experts of their day.