You probably learned about them in preschool with Dr. Seuss, but the mechanics of what makes a rhyme word actually work are surprisingly scientific. It isn't just about two words sounding "sorta" the same. It’s about phonology. It’s about the way your brain anticipates a specific acoustic pattern and feels a tiny hit of dopamine when that expectation is met.

Most people think a rhyme is just any two words that end with the same letter. That's wrong. "Pint" and "lint" look like they should get along, but they don't. They’re eye rhymes—visual phonies. A real rhyme is about the sound of the stressed vowel and everything that follows it. If you’ve ever found yourself stuck halfway through a greeting card or a song lyric, you know the frustration. You're hunting for that perfect phonetic anchor.

What is a Rhyme Word Exactly?

At its most basic level, a rhyme word is a word that shares an identical terminal sound with another word, starting from the last stressed syllable. Linguists like to get technical about this. They talk about the "onset" and the "rime." The onset is the consonant sound at the start of the syllable, and the rime is the vowel and anything that comes after. To have a "perfect rhyme," you need different onsets but identical rimes.

Take "cat" and "hat."

The "c" and "h" are the onsets. They're different.

The "at" is the rime. It's the same.

Boom. Rhyme.

But it gets weirder when you look at words like "believe" and "leave." These rhyme because the stress falls on the "lieve" part of both words. If the stress is off, the rhyme usually feels "slant" or broken. It’s why rappers and poets sometimes bend the pronunciation of a word—forcing the stress to land where it shouldn't just to make the sonic connection stick.

The Different "Flavors" of Rhyme

We usually only think about the "cat/hat" variety, which experts call "masculine rhyme." It’s punchy. It’s one syllable. But English is a messy language. We have "feminine rhymes," which involve two syllables, like "glitter" and "bitter." The first syllable is stressed, and the second is an unstressed echo.

Then there's the stuff that drives songwriters crazy: the mosaic rhyme. This is when one long word rhymes with a phrase made of multiple short words. Think of "puzzling" rhyming with "muzzle him." It’s clever, a bit showy, and honestly, hard to pull off without sounding like you're trying too hard.

Slant Rhymes: The Secret Weapon of Modern Music

If you listen to Taylor Swift or Kendrick Lamar, you'll notice they don't always use perfect rhymes. They use "slant rhymes" (also called half rhymes or near rhymes).

"Bridge" and "grudge."

"Young" and "song."

These words share similar consonant sounds or vowel sounds, but they aren't identical. Why use them? Because perfect rhymes can sometimes sound childish or predictable. If every line in a serious song ended in "heart" and "part," you’d roll your eyes. Slant rhymes allow for more complex storytelling because they open up a much wider vocabulary.

Why Our Brains Are Hardwired for This

Why do we care? Why does a rhyme word make a slogan more memorable?

💡 You might also like: Why a 14 Day Forecast Chicago Can Be So Wrong (And How to Read It Anyway)

Psychologists call it "the rhyme-as-reason effect." There was a famous study at Lafayette College where researchers gave people two versions of the same proverb. One rhymed, and one didn't. Participants consistently rated the rhyming versions as more "truthful."

"Woes unite foes" was seen as more accurate than "Woes unite enemies."

It’s a cognitive bias. Our brains process rhyming information more fluidly. Because it’s easy to say and easy to remember, we subconsciously assume it must be true. Advertisers have known this for decades. "Don't just graze, Pringles please." It sticks. It’s annoying, but it works.

The Trouble with "Orange" and Other Myths

You’ve heard the trivia. Nothing rhymes with orange.

Well, sort of.

Technically, "sporange" (a botanical term for a sac where spores are made) is a perfect rhyme. But nobody uses that in a love poem. "Silver" is another tough one, though some poets point to "chilver" (a female lamb).

"Month?" Nothing.

"Purple?" "Curple" is a word for a strap on a horse’s saddle, but good luck making that sound cool in your debut rap single.

The reality is that English is a Germanic language with a massive influx of French and Latin. This creates huge clusters of rhyming words for some sounds (the "-ate" or "-ing" sounds) and leaves others completely isolated. When a word has no perfect match, it's called a "refractory" word.

Using Rhyme Without Sounding Like a Nursery Rhyme

If you're writing, whether it's a poem or a marketing pitch, the goal isn't just to find a rhyme word. It's to find the right one.

- Avoid the obvious. "Fire" and "desire" have been used enough. If you're stuck in a cliché, move to a slant rhyme.

- Watch your meter. A rhyme at the end of a clunky, uneven sentence feels like a car crash. The rhythm (the "meter") matters just as much as the sound.

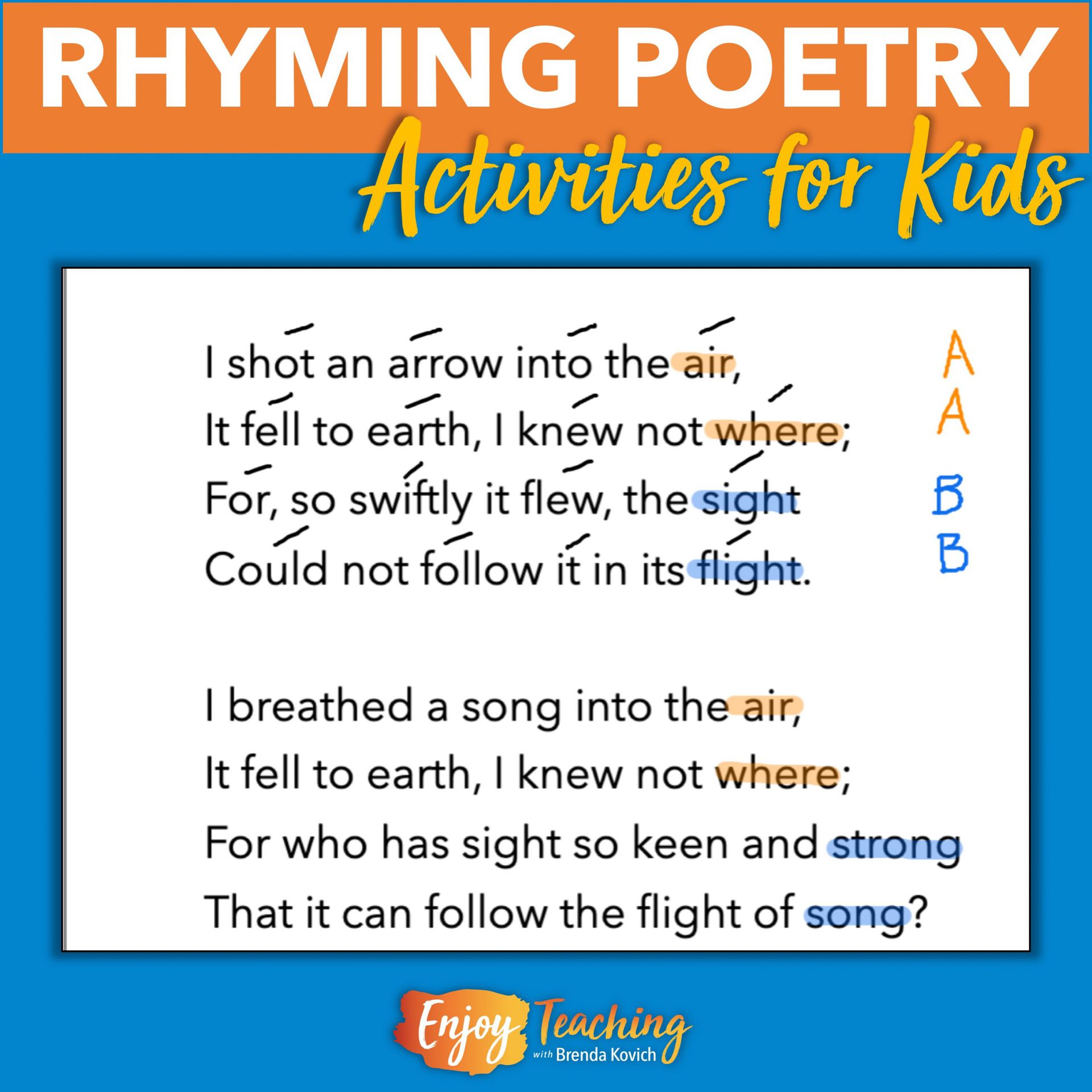

- Internal rhyme is your friend. You don't have to wait until the end of the line. Placing rhyming words inside the sentence—"The light of the night was a sight"—creates a subtle, melodic texture that feels more sophisticated than a standard AABB rhyme scheme.

Real-World Action Steps for Writers

If you're trying to improve your use of rhyme, don't just reach for a rhyming dictionary immediately.

- Read aloud. Your ears are better at detecting "false" rhymes than your eyes are. If a rhyme feels forced or "clunky" when spoken, it won't work on the page.

- Study Hip-Hop. Rappers like MF DOOM or Eminem are masters of multi-syllabic and internal rhyming. They don't just rhyme the last word; they rhyme entire phrases.

- Use rhyming for emphasis only. In business writing or non-fiction, a rhyme should be the "hook" or the "mic drop." Use it for your brand name or your concluding thought. If you use it too much, you lose authority.

The next time you're looking for a rhyme word, remember that you're tapping into a deep-seated human preference for pattern and symmetry. Whether it's a "perfect" match or a "slant" suggestion, the goal is to create a sense of resolution. It’s about finishing the pattern.

To master this, start by identifying the stressed vowel in your target word. Work backward from there. If you're stuck on a "refractory" word like "month," stop fighting the language. Switch the word order. Move the difficult word to the middle of the sentence and end on a word with more "friends" in the English vocabulary. Logic and phonetics are the two tools you need to make any rhyme feel natural rather than forced.