You’re sitting at your laptop, staring at a blinking cursor. You have a great idea. Maybe it’s a proposal for a new project at work, or maybe it’s just a really spicy take on LinkedIn. You type it out, hit send, and then… nothing. Total silence. It’s frustrating. You start wondering if your writing just sucks. But honestly? It’s probably not your grammar or your vocabulary. You likely just ignored the rhetorical situation in writing, which is basically the invisible set of rules that governs whether people actually care about what you have to say.

Writing isn’t a vacuum. It’s a conversation.

💡 You might also like: Why is Gas Going Down in Price? What's Actually Behind the 2026 Slump

If you walk into a funeral and start cracking jokes about the buffet, you’ve misread the room. If you write a formal legal brief using "rizz" and "no cap," you’ve failed the assignment. Every single piece of communication happens within a specific context. In the academic world, we call this the rhetorical situation. It sounds fancy. It’s not. It’s just the relationship between you, your audience, and the world around you at the exact moment you decide to open your mouth—or your laptop.

The Bitzer vs. Vatz Debate: Does the Situation Create the Writing?

Back in 1968, a guy named Lloyd Bitzer wrote a paper called The Rhetorical Situation. He argued that situations actually call writing into existence. Think about it. A building is on fire. That "situation" demands a specific response: someone yelling "Fire!" or calling 911. Bitzer thought that the situation dictates the response. He called this the "exigence"—an imperfection marked by urgency. It’s the "why" behind the "what."

But then came Richard Vatz.

Vatz basically told Bitzer he was wrong. He argued that the situation doesn’t exist until the rhetor (the writer) defines it. To Vatz, the world is a mess of random events, and we choose what is important by writing about it. If a politician gives a speech about the "crisis at the border," they are creating the rhetorical situation by naming it a crisis. Without the speech, it’s just people moving.

Who’s right? Both.

When you’re trying to figure out what a rhetorical situation in writing looks like for your own work, you have to balance these two. You’re responding to a real need (Bitzer), but you’re also framing how people see that need (Vatz). If you’re writing a cover letter, the job opening is the "exigence." But how you describe your skills creates the "situation" where you are the only logical choice for the role.

Breaking Down the Rhetorical Triangle (And Why It’s Not Enough)

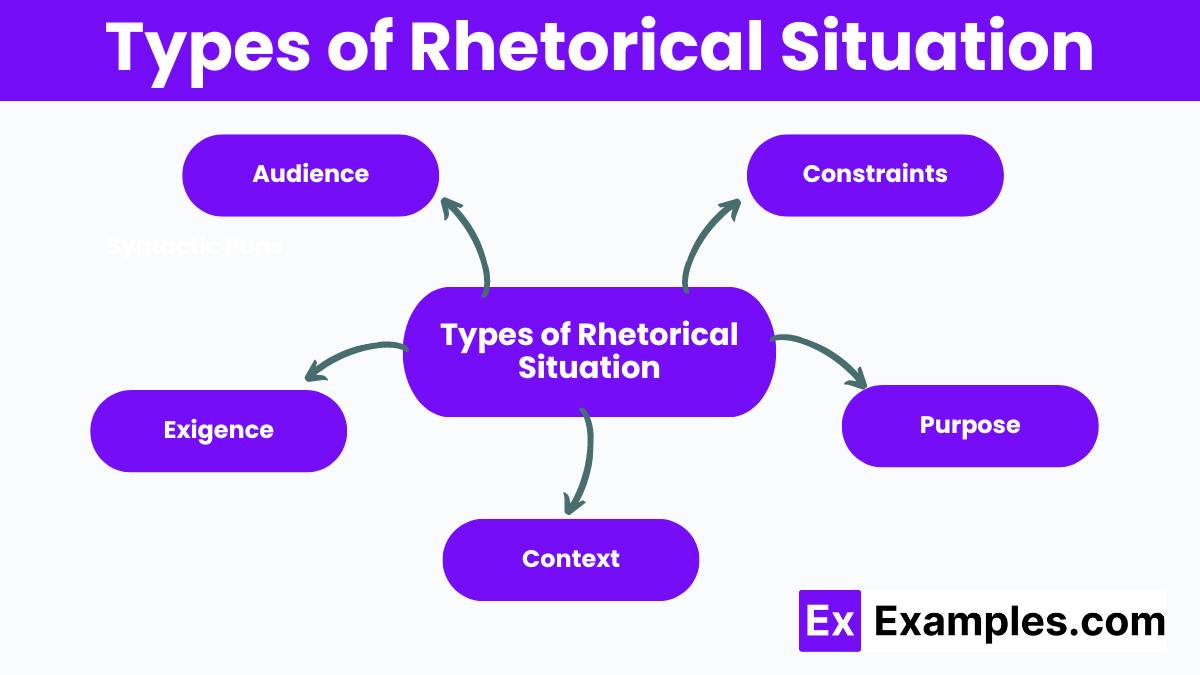

Most people learn about the rhetorical triangle in high school: Author, Audience, Message. It’s a bit basic, honestly. If you want to actually influence people, you need to look at the expanded version, often called the Rhetorical Circle or the Five Elements.

1. The Writer (Ethos)

Who are you? No, really. Why should I listen to you? Your "persona" matters more than your actual identity sometimes. If you’re writing a medical blog post but you’re a high school dropout with no medical training, your rhetorical situation is broken from the jump. You lack the ethos—the credibility—to occupy that space.

2. The Audience (Pathos)

This is where most writers fail. They write for themselves. They use jargon they like or tell stories only they find funny. To master the rhetorical situation in writing, you have to perform a sort of mental colonoscopy on your reader. What are they afraid of? What keeps them up at 2:00 AM? If you’re writing a pitch for a VC, they don't care about your "passion." They care about ROI. If you’re writing a breakup text, "ROI" is the last thing you should mention.

3. The Purpose (Logos)

What is the "win" here? If you don’t know what you want the reader to do after reading, don’t write it. Are you trying to persuade, inform, entertain, or just vent? A lot of corporate emails fail because they try to do all four at once and end up doing none of them well.

4. The Exigence

This is the spark. Why now? Why not yesterday? Why not next year? In the world of SEO and digital marketing, exigence is often driven by trends or news cycles. If you write about "How to buy Bitcoin" in 2011, you’re a visionary. If you write it when the market is crashing and everyone is losing their shirts, you’re either a contrarian or a fool. The timing changes the meaning.

5. Constraints

Constraints are the "walls" of your writing. They include things like:

- Medium: An Instagram caption has different constraints than a white paper.

- Culture: What is acceptable to say in a boardroom in Tokyo is different than a startup in Austin.

- Time: If you have 30 seconds of someone’s attention, you can’t spend 20 of them on an introduction.

Real-World Failure: When the Situation Goes South

Let’s look at a real-world example of someone ignoring the rhetorical situation. Remember the infamous Pepsi ad with Kendall Jenner?

The "exigence" was the global conversation around social justice and protest movements (like Black Lives Matter). Pepsi tried to enter that rhetorical situation. The problem? Their "persona" (a massive corporate soda brand) didn't match the gravity of the "audience" (people fighting for systemic change). The "message" (soda fixes police brutality) was a catastrophic misread of the "constraints" of reality.

They had all the elements of a rhetorical situation, but they aligned them poorly. They tried to use a "lifestyle" tone for a "political" exigence. It felt hollow. It felt fake. It was a rhetorical disaster.

In contrast, look at how Patagonia handles their writing. When they ran the "Don't Buy This Jacket" ad on Black Friday, they understood the situation perfectly. The exigence was the environmental impact of consumerism. Their audience consisted of outdoor enthusiasts who value sustainability. Their constraints were the irony of being a company that sells things while telling people not to buy things. Because they leaned into that irony and stayed true to their ethos, the ad was a massive success.

How to Analyze Your Own Rhetorical Situation Before You Type a Single Word

Before you start writing your next big project, you need to do a quick audit. Don’t just wing it. Ask yourself these questions.

What is the "stasis"? This is an old legal concept. Basically, what is the core point of disagreement? If you’re writing a rebuttal to a coworker, are you disagreeing on the facts (did the revenue go down?) or the definition (was a 2% drop actually "down" or just "noise"?) or the quality (was the drop a "disaster" or a "learning opportunity"?) or the policy (should we fire the manager or change the software?). If you argue about policy when your boss is still arguing about facts, you’re going to lose.

Who is the "Invoked Audience"?

There is the real audience (the people who actually read your stuff) and the invoked audience (the version of the reader you create in your head). If you write like your reader is a genius, they will feel flattered and try to live up to that. If you write like they’re an idiot, they’ll get defensive. You can actually "shape" your audience by how you address them.

What is the "Kairos"?

Kairos is the Greek word for "the opportune moment." It’s about "the right time." If you ask for a raise right after your boss’s dog died, your kairos is terrible. If you ask right after you just landed a $1M account, your kairos is perfect. The rhetorical situation in writing is heavily dependent on this.

The Myth of the "Universal" Writer

There is no such thing as "good writing" in a general sense.

There is only writing that is effective for a specific situation. A poet might be a terrible technical manual writer. A journalist might struggle to write a screenplay. This is because each of these genres has its own "rhetorical atmosphere."

When you hear someone say "I’m a good writer," what they usually mean is "I am good at identifying and adapting to different rhetorical situations." They are chameleons. They can sense the exigence, identify the audience's pain points, and adjust their ethos to match.

👉 See also: Mortgage Rates November 2024: Why Most Buyers Got It Wrong

Actionable Steps to Master Your Rhetorical Situation

Stop thinking about your "content" and start thinking about your "context."

- Define the "So What?" Before writing, finish this sentence: "I am writing this because [Real World Event] happened, and if I don't write this, [Negative Consequence] will occur." If you can't finish that sentence, your exigence is too weak.

- Audit your Ethos. Look at your social media or your professional bio through the eyes of a stranger. Does your "vibe" match the "value" you are trying to provide? If you're giving financial advice but your profile picture is you doing a keg stand, you have a rhetorical misalignment.

- Map the Constraints. Write down three things you cannot do in this specific piece of writing. Can't be too long? Can't use slang? Can't mention a competitor? Knowing the boundaries makes the writing inside them much stronger.

- Listen Before You Leap. If you’re entering a new community (like a new subreddit or a new industry), read for a week before you post. Understand the existing rhetorical situations. What are people complaining about? What jokes are tired? What "ethos" do the leaders of that community have?

- Test the Kairos. Is today the best day for this? Sometimes sitting on a draft for 24 hours changes the entire situation. A news event might happen that makes your post look insensitive, or a new study might come out that proves your point even better.

Writing is a tool, not a trophy. It exists to do work in the real world. By focusing on the rhetorical situation in writing, you stop shouting into the void and start actually talking to people. You move from being a "content creator" to a "rhetorician." It's a lot more powerful.

Check your tone. Verify your timing. Know your "why." The rest is just typing.