Ever stared at a string of six random characters like #FF5733 and wondered why it looks like a neon sunset on your screen? It feels like some weird secret handshake between designers and engineers. Honestly, it kind of is. When we talk about rgb color in hex, we’re basically translating how humans see light into a language that a graphics card can actually digest without choking.

Computers are fundamentally lazy. They don't want to deal with names like "periwinkle" or "burnt sienna" because those words are subjective and messy. Instead, they want numbers. Specifically, they want bits.

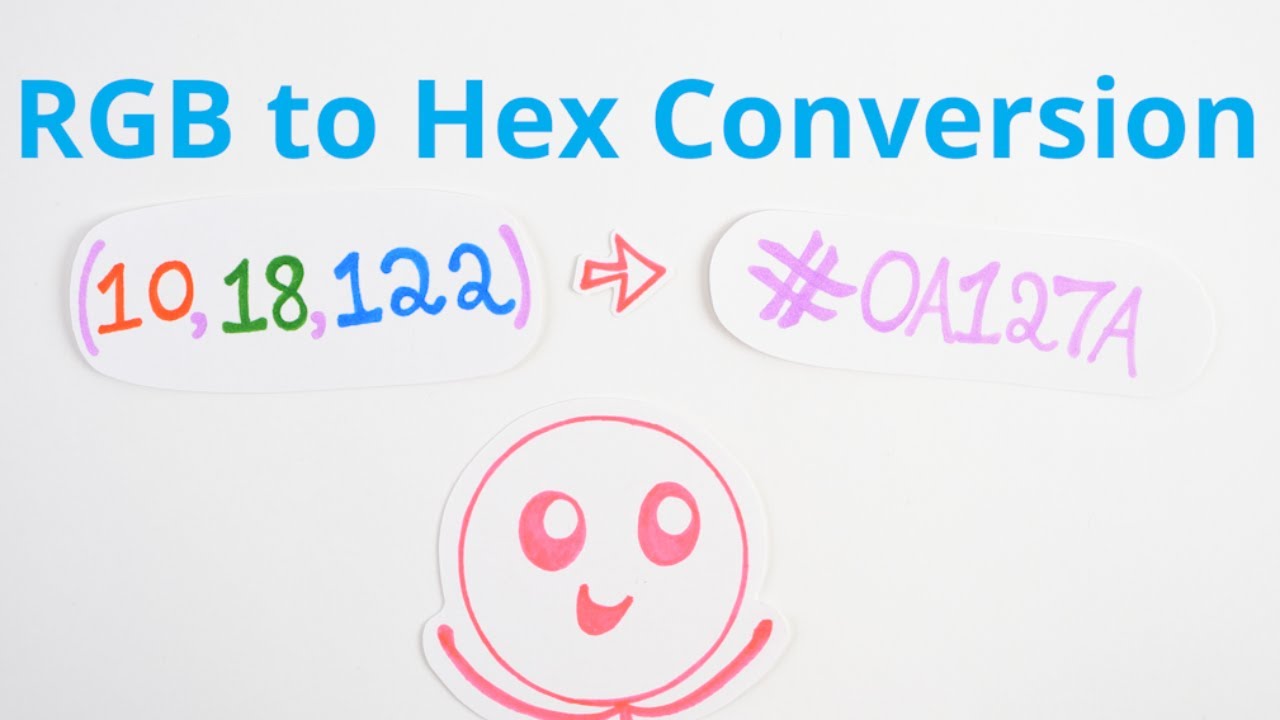

The Math Behind the Magic

Hexadecimal is just a base-16 numbering system. While we humans use base-10 (because we have ten fingers, mostly), computers love powers of two. A hex code is a shorthand way of writing out the binary values for Red, Green, and Blue.

Each color gets two digits.

The first two are Red, the middle two are Green, and the final two are Blue. It’s always that order. No exceptions. If you see #00FF00, you’re looking at zero red, maximum green, and zero blue. It’s the purest, most obnoxious green you’ve ever seen.

Why the Letters?

You might notice that hex codes use letters A through F. Since we need to represent the number 15 in a single character to keep the code compact, we ran out of numbers at 9. So, A equals 10, B equals 11, and so on, until F hits 15.

When you see #FFFFFF, it’s basically the computer saying "turn every single sub-pixel on to its highest intensity." That's how you get white. If you flip it to #000000, you’ve told the screen to go dark. Total black.

How We Get Millions of Colors

There’s a reason rgb color in hex is the industry standard for the web. Because each of the three color channels (R, G, and B) has 256 possible levels of intensity (from 00 to FF), the math gets big fast.

$256 \times 256 \times 256 = 16,777,216$

That is over 16 million colors.

Most people can’t even see the difference between #FF0000 and #FE0000. It’s a tiny, microscopic shift in the red channel. But for a high-end OLED display, that distinction matters. It’s the difference between a smooth gradient and "banding," which is those ugly, blocky lines you see in low-quality images.

The Practical Side of the Palette

If you’re building a website or just messing around in Canva, you've probably noticed that some hex codes are easier to remember. "Web-safe colors" used to be a big deal back in the 90s when monitors could only show 256 colors total.

Those days are dead.

Now, we use hex for consistency. If you use a specific shade of blue for a brand logo, you want that blue to look the same on an iPhone, a Dell monitor, and a smart fridge. Using rgb color in hex ensures that the data being sent to the hardware is identical, even if the hardware itself interprets that data slightly differently based on its calibration.

Common Hex "Gotchas"

- The Hash Sign: In CSS and most design software, that

#symbol is mandatory. It tells the system, "Hey, don't read this as a word, read it as a hex value." - Short-hand: You might see #F00. That’s just a lazy way of writing #FF0000. The browser just doubles each digit.

- Alpha Channels: Sometimes you’ll see eight characters, like #FF000080. That last "80" is the transparency (alpha). It’s not strictly "RGB" anymore; it’s RGBA.

Why Designers Still Prefer Hex Over RGB Triplets

You’ll often see RGB written as rgb(255, 87, 51). It’s the exact same color as #FF5733.

So why do we use hex?

It's just shorter. When you're writing thousands of lines of code, saving those extra characters makes the file smaller and easier to scan visually. It's a "developer experience" thing. Plus, copying and pasting one string is way faster than typing out three separate numbers with commas.

Digital Light vs. Physical Ink

One thing people often get wrong is trying to use hex codes for printing.

Don't do that.

Hex is for screens. Screens use additive color. You start with a black void and add light. Printing uses subtractive color (CMYK). You start with white paper and add ink to block light.

If you take a vibrant #00FFFF (Cyan) from your screen and try to print it, it will look dull. Physical ink simply can't glow like a LED. This is a hard limit of physics, not a software bug. Designers like Erik Spiekermann have often pointed out that the transition from digital light to physical pigment is where most amateur projects fall apart.

🔗 Read more: The Big Bang: What Most People Get Wrong About How the Universe Started

The Future of Hex

We are starting to move toward even more complex systems like P3 color gamuts and High Dynamic Range (HDR). These systems can display colors that actually sit outside the traditional sRGB range that hex was built for.

Does that mean rgb color in hex is going away?

Probably not anytime soon. It’s too baked into the infrastructure of the internet. We’ll likely just keep appending more digits or using new CSS functions like color(display-p3 ...) to bridge the gap. For now, hex remains the king of the color hill.

Actionable Tips for Mastery

To get better at using color in your digital projects, stop relying on the color picker every single time. Try to "read" the hex.

- Grey Scale: If all three pairs are the same (#333333, #A1A1A1), the color will always be a shade of grey.

- Warmth: If the first two digits (Red) are much higher than the others, your color is going to be warm.

- Cooling Down: High values in the last pair (Blue) naturally create cooler, more professional-looking tones.

Start by memorizing the basics: #000 (Black), #FFF (White), #F00 (Red), #0F0 (Green), and #00F (Blue). Once you understand that these are just levels of light intensity, you’ll stop seeing #FF5733 as a random string and start seeing it as a recipe for a very specific orange.

If you are working on a project right now, grab a tool like Adobe Color or Coolors. Use them to see how these hex values relate to each other mathematically. It’ll make your designs look less like an accident and more like a calculated choice.