It is the moment where millions of listeners reach for the "skip" button. You’re sitting there, vibing to the acoustic warmth of "Cry Baby Cry," and then it happens. A posh, disembodied voice repeats the words "Number nine... number nine... number nine..." and suddenly your living room is filled with the sounds of screaming, sirens, backward orchestras, and a burning building. Revolution 9 The Beatles didn't just break the rules of pop music; it set the rulebook on fire and threw the ashes into the wind.

Most people call it noise. Critics have spent over half a century labeling it a pretentious indulgence or a sign that the greatest band in history was finally, irrevocably, falling apart. Honestly? They aren't entirely wrong. But if you think it’s just a random mess of sound, you’re missing the point of why it exists in the first place. This wasn't a song. It was an audio painting of a world in the middle of a nervous breakdown.

The Chaos Behind the Tape Loops

To understand why "Revolution 9" sounds like a nightmare, you have to look at what was happening inside Abbey Road in June 1968. John Lennon was obsessed. He wasn't interested in writing another "I Want to Hold Your Hand." He was hanging out with Yoko Ono, exploring the world of musique concrète, and trying to capture the feeling of a literal revolution in sound.

While Paul McCartney was away in New York, John took over Studio 03. He gathered dozens of tape loops. He raided the EMI archives. George Harrison helped out, and Yoko was right there in the thick of it, whispering phrases into the microphone. They had machines running in multiple rooms, with engineers holding pencils to keep the loops from tangling. It was physical, grueling work. Imagine John Lennon crawling around on the floor, hand-feeding bits of magnetic tape into a machine just to see what kind of screeching noise it would make.

💡 You might also like: Songs by Tyler Childers: What Most People Get Wrong

George Martin, the band’s legendary producer, actually tried to talk John out of putting it on the album. He thought it was too much. Even Paul McCartney, who was usually the one pushing the experimental envelope with things like "Tomorrow Never Knows," wasn't a fan. He felt it didn't fit the "Beatles" brand. But John won. He insisted it was the direction the world was heading.

What You’re Actually Hearing (The Sound Sources)

There is a common misconception that "Revolution 9" is just random feedback. It’s actually a incredibly dense collage of hundreds of different sounds. If you listen closely—like, really closely—you can hear the fragments of a civilization being torn down and rebuilt.

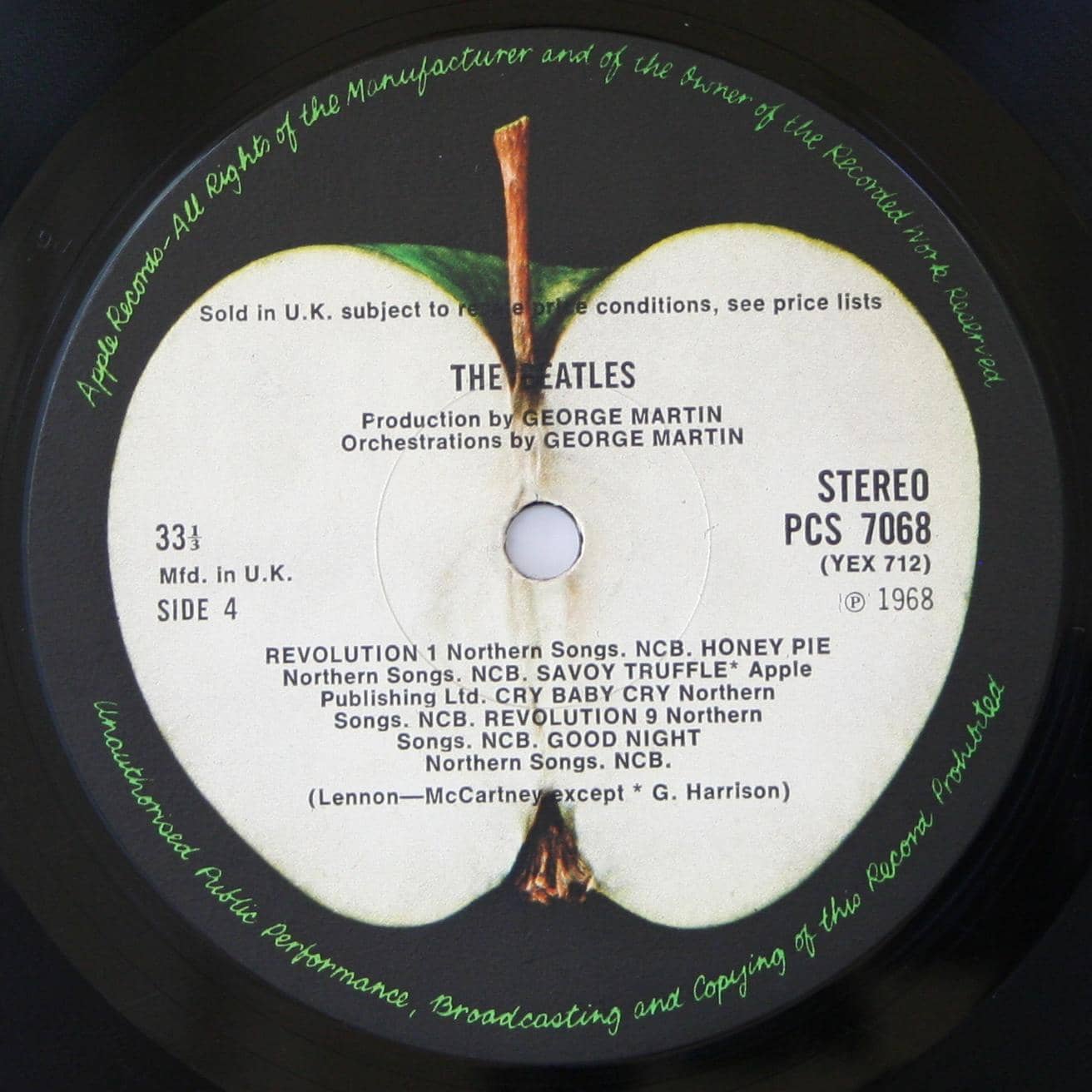

- The "Number Nine" Voice: That’s actually an old Royal Academy of Music examination tape. The engineer, Stuart Eltham, found it in the archives. John loved the clinical, haunting tone of the voice and looped it to create the track's rhythmic anchor.

- The Classical Snips: You’re hearing bits of Sibelius' Seventh Symphony, Schumann, and even a choir. It’s like the ghost of high culture haunting a riot.

- The Beatles Themselves: There are fragments of the "Revolution 1" ending. If you’ve ever wondered what happened to the 10-minute version of that song, the "Revolution 9" soundscape is where the chaotic jam session went to die.

- Environmental Noise: Screaming fans, crashing glass, and the sound of a roaring fire.

John once described it as "a drawing of a revolution." He wanted the listener to feel the violence of the late 60s—the Vietnam War, the riots in Paris, the assassinations of RFK and MLK. He basically wanted to put the news on a record, but instead of words, he used pure atmosphere.

📖 Related: Questions From Black Card Revoked: The Culture Test That Might Just Get You Roasted

The Charles Manson and Paul is Dead Mythos

You can’t talk about Revolution 9 The Beatles without mentioning the weird, dark baggage it picked up after its release. It’s a bit chilling, honestly. Charles Manson became obsessed with the White Album, and he believed "Revolution 9" was a prophetic message about an impending race war. He thought the "number nine" was a reference to Revelation 9 from the Bible. It’s a tragic, horrifying footnote that John Lennon found deeply disturbing.

Then there’s the "Paul is Dead" crowd. If you play the "number nine" loop backward, some swear it says "Turn me on, dead man." People spent hours in dark rooms during the 70s spinning their vinyl backward, convinced that the sound of a car crash and fire in the track was a literal recreation of McCartney’s supposed fatal accident. It wasn't, obviously. But the fact that the track is so abstract makes it a perfect Rorschach test for the paranoid.

Why It Still Matters Today

Does anyone actually enjoy listening to it? Probably not in the same way they enjoy "Blackbird" or "While My Guitar Gently Weeps." But "Revolution 9" is the reason your favorite experimental indie band or hip-hop producer feels comfortable using sound effects and samples today. It was the moment the biggest band on Earth said, "The studio is an instrument, and we can do whatever we want with it."

👉 See also: The Reality of Sex Movies From Africa: Censorship, Nollywood, and the Digital Underground

It was a middle finger to the industry. It was a statement of absolute artistic freedom. In a world of three-minute pop songs designed for the radio, the Beatles put an eight-minute avant-garde sound collage on an album that they knew would sell millions of copies. That is objectively ballsy.

How to Actually Experience Revolution 9

If you want to get the most out of this track, stop treating it like a song. You can't hum it. You can't dance to it.

- Use Good Headphones: The stereo panning is insane. Sounds fly from left to right, creating a 3D space in your brain.

- Turn Off the Lights: This is immersive media. It’s meant to be a "happening."

- Don't Look for a Pattern: Just let the sounds wash over you. It's about the texture, the contrast between the calm voice and the chaotic screaming.

- Listen to the Context: Play "Cry Baby Cry" first, let "Revolution 9" play out, and then listen to how "Good Night" acts as a lullaby to wake you up from the nightmare.

The track is a bridge. It’s the sound of the 1960s ending and something much more uncertain beginning. Whether you love it or hate it, Revolution 9 The Beatles remains the most daring thing a pop group has ever committed to wax. It’s uncomfortable, it’s long, and it’s weird. But that’s exactly why we’re still talking about it sixty years later.

For those looking to dive deeper into the Beatles' experimental phase, start by comparing the "Revolution 1" take 20 (available on the 50th Anniversary box set) with the final collage. You can hear exactly where the "song" ends and the "revolution" begins, providing a clear window into John Lennon’s chaotic creative process during the summer of 1968.

Check out the original mono mix if you can find it; it hits differently than the stereo version, feeling much more claustrophobic and aggressive. Understanding the gear used—the Studer J37 four-track recorders and the manual tape manipulation—really highlights how much of a technical feat this was before digital editing existed.