Ottorino Respighi was kind of a rebel, but not in the way we usually think of classical composers. He wasn’t trying to break music apart like Schoenberg or Stravinsky. Instead, he wanted to make it cinematic before "cinematic" was even a thing. The Pines of Rome (Pini di Roma) is basically a high-definition, 4D IMAX experience written for an orchestra in 1924.

You’ve probably heard the finale. It’s that massive, floor-shaking march where the brass players literally stand up in the balconies to surround the audience. It feels like a victory. But if you look closer at what Respighi was actually doing, it’s a lot weirder—and more technically ambitious—than just a loud song about some trees.

He was obsessed with the idea that nature holds onto memories. He didn't just want to describe the trees; he wanted to use them as witnesses to history. From kids playing in the Borghese gardens to the ghosts of ancient Roman legions marching up the Appian Way, the music is a time machine.

What People Get Wrong About Respighi's Vision

Most critics back in the day called Respighi a "superficial" orchestrator. They thought he was all flash and no substance. That’s a total misunderstanding of his goals. Respighi was part of the generazione dell'ottanta (the generation of 1880), a group of Italian composers tired of opera dominating everything. They wanted to prove Italy could do symphonic music just as well as the Germans.

The Pines of Rome isn't just "program music" (music that tells a story). It’s a psychological landscape.

Take the second movement, "Pines Near a Catacomb." It’s gloomy. It’s oppressive. You can almost feel the dampness of the underground burial chambers. He uses a chant-like melody that sounds ancient, but he layers it with these low, dissonant echoes in the muted horns and cellos. It’s not "pretty" music. It’s a deliberate attempt to make the listener feel the weight of centuries of dead Romans under their feet. Honestly, it’s closer to a horror movie soundtrack than a traditional symphony.

The Gramophone Scandal

Here is a fun fact that people often miss: Respighi was the first guy to put a "sample" in a major orchestral work.

In the third movement, "The Pines of the Janiculum," he instructs the percussionist to play a specific recording of a nightingale. Not a flute imitating a bird. A literal record player.

✨ Don't miss: Why ASAP Rocky F kin Problems Still Runs the Club Over a Decade Later

People lost their minds.

The traditionalists thought it was cheating. They argued that if you want a bird sound, you should write it for an instrument. But Respighi wanted the real thing. He even specified the exact record number in the score: Ricordi No. R. 6105. He was basically the grandfather of electronic music and sampling, seventy years before it became a staple of hip-hop and pop. He understood that reality has a texture that instruments sometimes can't capture.

Breaking Down the Four Movements

You have to think of this piece as a suite of four distinct snapshots. They aren't connected by a recurring melody, but by the vibe of the city itself.

The opening, "I pini di Villa Borghese," is pure chaos. It represents children playing, shouting, and running in circles. The rhythms are jagged. It’s fast. It’s bright. The trumpets are constantly "yelling" over the rest of the orchestra. It’s meant to be overwhelming, capturing that specific energy of a crowded park in the Italian sun.

Then everything drops away.

The transition into the catacombs movement is jarring. The silence feels heavy. This is where Respighi shows off his skills as a master of "tone color." He uses the piano and the organ to create a subterranean vibration that you feel in your chest more than you hear in your ears.

The third movement is the dream sequence. It’s night on the Janiculum hill. This is where that nightingale shows up. The piano ripples like moonlight on water. It’s incredibly romantic, but there’s an undercurrent of sadness. It’s the "calm before the storm" that makes the finale so effective.

🔗 Read more: Ashley My 600 Pound Life Now: What Really Happened to the Show’s Most Memorable Ashleys

The Appian Way: A Sound Pressure Masterclass

The final movement, "I pini della Via Appia," is what everyone waits for.

It starts with a heartbeat. A low, rhythmic thumping in the organ and the lower strings. It represents the sun rising over the ancient military road, but more importantly, it represents the ghost of a Roman consular army returning in triumph.

Respighi does something brilliant here. He doesn't start loud. He starts at a whisper. The tension builds for five straight minutes. It’s a "long crescendo," a technique popularized by Ravel in Boléro, but Respighi gives it more grit. He adds "buccine"—ancient-style trumpets. Since those don't really exist anymore, modern orchestras usually use flugelhorns or extra trombones placed in the back of the hall.

By the time the full orchestra hits the final chord, the sound is physical. It’s designed to be the loudest thing you’ve ever heard in a concert hall. It’s not just music; it’s an assault on the senses.

Why We Still Care in 2026

We live in a world of digital perfection, where every sound is quantized and cleaned up. The Pines of Rome feels human because it’s messy and ambitious. It’s a reminder that classical music doesn't have to be "polite."

Respighi was heavily influenced by his time in Russia, where he studied with Rimsky-Korsakov. You can hear that Russian influence in how he treats the brass—big, bold, and unapologetic. But the soul of the piece is purely Italian. It’s about the connection between the land and the people who lived on it two thousand years ago.

Critics like Virgil Thomson used to bash Respighi for being "vulgar." But what they called vulgarity, we now recognize as cinematic genius. John Williams (think Star Wars or Indiana Jones) owes a massive debt to Respighi. The way Williams builds brass fanfares and uses "shimmering" strings is straight out of the Respighi playbook.

💡 You might also like: Album Hopes and Fears: Why We Obsess Over Music That Doesn't Exist Yet

Nuance and Controversy

Is it a bit nationalistic? Maybe.

Written in 1924, during the rise of Mussolini’s Italy, the "glory of Rome" theme was definitely something the government liked. Respighi himself wasn't a hardcore political figure, but he certainly knew how to play to his audience. The piece celebrates a Roman past that the fascists were trying to resurrect.

However, if you strip away the politics, the music stands on its own as a feat of engineering. The complexity of the orchestration is staggering. Even today, conducting this piece is a nightmare because of the balance issues. If the brass is too loud, they drown out the strings. If the nightingale recording is too quiet, it sounds like a mistake. It requires a level of precision that most people don't realize when they're just enjoying the big "boom" at the end.

Practical Ways to Experience the Music

If you're new to this, don't just put it on in the background while you do dishes. You'll miss the whole point.

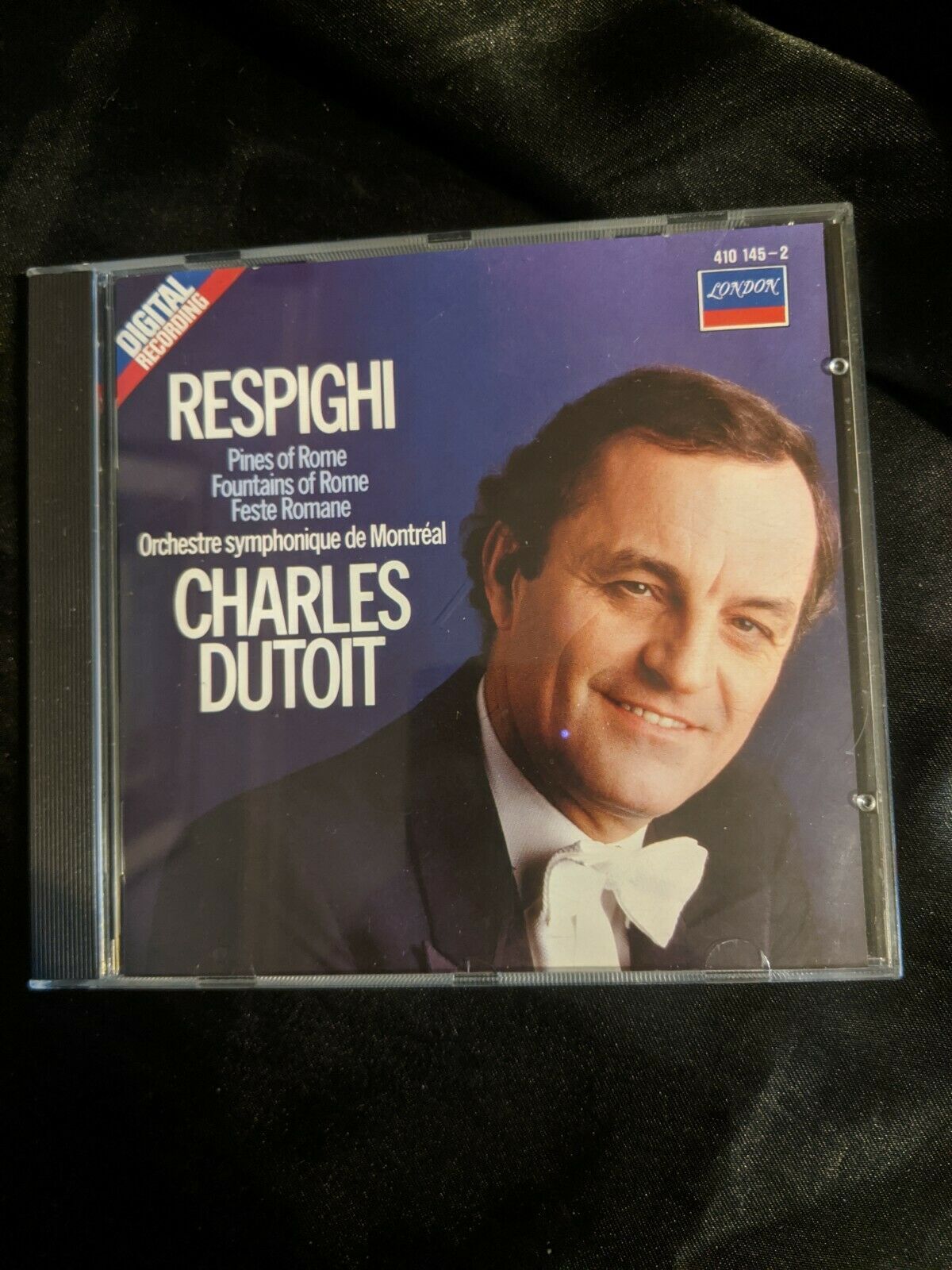

- Find a "Surround Sound" Recording: Look for a high-fidelity version (like the Chicago Symphony Orchestra under Fritz Reiner or the Montreal Symphony with Charles Dutoit). These conductors understood how to space out the sound.

- Use Good Headphones: You need to hear the low pedal notes of the organ in the second and fourth movements. Without a decent bass response, the piece sounds thin.

- Watch a Live Performance: This is one of the few pieces that must be seen to be believed. Watching the extra brass players stand up in the balcony during the finale is a core memory for most classical music fans.

- Compare the "Pines" to the "Fountains": This piece is part of a trilogy. The Fountains of Rome is more delicate and impressionistic, while Roman Festivals is even crazier and louder. Listening to all three gives you the full picture of Respighi’s "Roman" obsession.

The "actionable" takeaway here is to stop treating classical music like it’s a fragile museum piece. Respighi wrote The Pines of Rome to be a visceral, loud, and slightly scary experience. It’s meant to make your hair stand up. It’s meant to make you feel the weight of history.

Next time you listen, ignore the "classical" label. Treat it like a film score to a movie that hasn't been made yet. Focus on the textures—the grit of the Appian Way gravel, the chill of the catacombs, and the piercing cry of that 1924 nightingale. That’s where the real magic happens.

Actionable Next Steps

- Listen to the "Janiculum" movement specifically for the nightingale entry at the end. Notice how the orchestra fades out to let the "low-fi" recording take over. It’s a haunting contrast between live sound and recorded history.

- Track the tempo in the final movement. Use a metronome or just tap your foot. Notice how it never speeds up, even though it feels like it’s getting faster. The intensity comes entirely from the volume and the layering of instruments.

- Explore the "Trilogia Romana" in order: Fountains of Rome (1916), Pines of Rome (1924), and Roman Festivals (1928) to see how Respighi’s style became increasingly bold and experimental over twelve years.