You're sitting there staring at a blank email draft, wondering if your favorite Sociology professor even remembers that one paper you wrote about urban sprawl. It’s nerve-wracking. Honestly, getting a reference letter from professor mentors is one of those academic hurdles that feels way more personal than it actually is. Most students treat it like they’re asking for a massive, life-altering favor, but for faculty, this is literally part of the job description. It’s a transaction of academic capital.

But here is the thing: a mediocre letter is almost worse than no letter at all. If a professor just says, "Yeah, they were in my class and got an A," you’ve basically wasted a slot in your application. You need the "glow." You need them to talk about your intellectual curiosity, that time you challenged a theory in a seminar, or how you handled a data set that was falling apart.

Why the "A" Doesn't Actually Matter That Much

Most people think the grade is the headline. It isn't. According to data and common faculty sentiment often discussed in the Chronicle of Higher Education, admissions committees for grad school or hiring managers for entry-level roles already see your transcript. They know you got the A. What they don't know is if you're a nightmare to work with in a lab setting or if you actually contribute to group discussions.

A solid reference letter from professor sources focuses on soft skills disguised as academic achievements. Are you resilient? Do you take feedback without getting defensive? These are the "hidden" metrics. I’ve seen students with 3.2 GPAs beat out 4.0 students because a professor wrote three paragraphs about their "uncommon grit" during a difficult research project.

The Etiquette of the Ask

Don't be the person who emails on a Friday night asking for a letter due Monday morning. That is the fastest way to get a "no" or, worse, a rushed, template-based letter that smells like apathy.

Timing is everything. You want to give them at least four to six weeks. Why? Because professors are perpetually drowning in grading, committee meetings, and their own research. If you give them a month, you're a professional. If you give them a week, you're an emergency they didn't ask for.

✨ Don't miss: 100 Biggest Cities in the US: Why the Map You Know is Wrong

How to actually phrase the request

Don't just ask "Can you write me a letter?"

That's too vague. Instead, ask: "Do you feel you know my work well enough to write me a strong letter of recommendation for [Specific Program]?"

That word "strong" is your safety net. It gives them an out. If they hesitate, you don't want that letter anyway. A lukewarm recommendation is the "kiss of death" in competitive fields like med school or PhD programs. If they say yes, you need to hand-feed them the details. Send a "brag sheet." Give them your CV, your personal statement, and a reminder of which specific projects you did in their class. You are basically ghostwriting the highlights for them so they don't have to dig through old files.

When a Professor Says No (And Why It Happens)

It feels like a rejection of your entire soul, but it's usually just logistics. Maybe they are on sabbatical. Maybe they only write letters for students who took at least two of their classes. Or maybe—and this is the hard truth—they don't remember you well enough to be helpful.

I’ve talked to faculty at big state schools who have 300 students in a lecture hall. If you never went to office hours, they literally cannot write anything substantive about you. In that case, a "no" is actually a favor. They are preventing you from having a hollow letter that would hurt your chances.

🔗 Read more: Cooper City FL Zip Codes: What Moving Here Is Actually Like

Seeking out the "Adjunct Factor"

There is a weird myth that you only want "Full Professors" or Department Chairs to write your letters. That is often bad advice. An adjunct instructor or a Teaching Assistant who saw you every single day in a small lab is going to write a much more compelling reference letter from professor figures than a world-famous researcher who doesn't know your last name.

Authority matters, but intimacy (the professional kind) wins. Admissions officers at places like Harvard or Stanford have explicitly stated in various forums that they prefer a detailed letter from a junior faculty member over a two-sentence "He was fine" from a Nobel Laureate.

Logistics and the Dreaded FERPA Waiver

At some point, you’ll hit a checkbox asking if you "waive your right to view this recommendation."

Waive it.

Always.

💡 You might also like: Why People That Died on Their Birthday Are More Common Than You Think

If you don't waive your right, the person reading the letter thinks the professor was holding back because they knew you’d eventually read it. It robs the letter of its perceived honesty. It's a weird psychological game, but that's how the system works. When you waive your right, you’re telling the admissions committee, "I trust this person’s assessment of me completely." It adds a layer of authenticity that you can't get any other way.

Common Pitfalls That Kill Your Credibility

- The Template Trap: If the professor asks you to write the letter and they will just sign it, be careful. This happens more than people admit. If you do this, don't make yourself sound like a superhero. Use moderate, professional language. If it sounds like a PR press release, people will see right through it.

- The Wrong Subject: Don't ask a Math professor for a letter for a Creative Writing program unless that math professor can specifically speak to your writing or logic skills in a way that translates.

- Missing Deadlines: Most systems send an automated link to the professor. Remind them gently a week before it's due. Professors are human; they forget stuff. A polite "Just checking in" email isn't annoying—it's helpful.

The Reality of Digital Portals

In 2026, nobody is mailing physical letters with wax seals. It’s all Interfolio, Slate, or custom university portals. Make sure you’ve entered their email address correctly. You’d be surprised how many "missing" letters are just sitting in a spam folder because of a typo in the professor's .edu address.

Actionable Steps for a Better Letter

If you want a reference letter from professor mentors that actually moves the needle, stop treating it like a bureaucratic hurdle and start treating it like a relationship.

- Audit your relationships. Look at your transcript. Who gave you an A- but also gave you heavy feedback on your final project? That’s your best candidate.

- Prepare the "Packet." Before you even ask, have a folder ready with your resume, your best paper from their class (with their original comments if possible), and a list of the schools you're applying to.

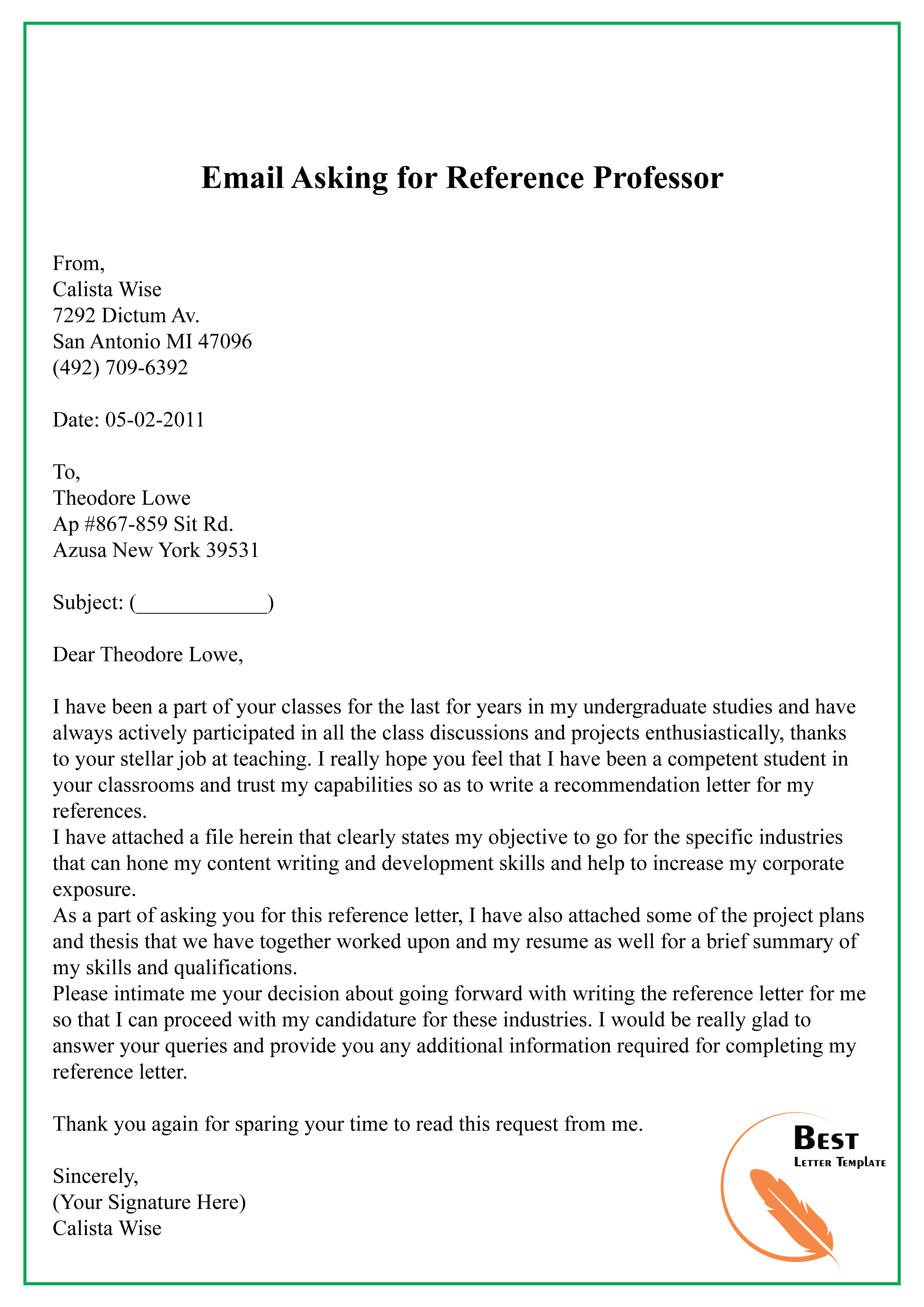

- The "Ask" Email. Keep it short. Remind them who you are, which class you took, and what your goal is. Ask for a "strong" letter.

- The Follow-up. Once they agree, send the formal links immediately.

- The Gratitude. This is the step everyone forgets. Send a thank-you note after they submit it. And for heaven's sake, tell them if you got in! Professors actually like knowing their effort resulted in a win for the student.

The best letters aren't about being perfect. They are about being a real person who showed growth. If you struggled at the start of a semester and finished strong, that narrative of improvement is gold for a reference letter from professor to highlight. It shows you can handle the "hard stuff," which is exactly what grad schools and employers are looking for.

Focus on the narrative, give them the tools to write it, and respect their time. That’s how you get a letter that actually opens doors.