Chemistry is weirdly obsessed with things that don't actually exist in isolation. You can’t just have a pile of "reduction" sitting on a table. It doesn't work like that. If something is going to gain an electron, some other poor atom has to lose one. It’s a cosmic game of hot potato. This brings us to the core of everything from the battery in your iPhone to the reason your old bike is covered in rust: reducing and oxidizing agents.

Honestly, the terminology is a mess. It’s a linguistic trap that has tripped up chemistry students for over a century. We call something an "oxidizing agent," but that thing itself gets reduced. It's like calling a travel agent a "traveling agent" even though they stay in the office while you go to Maui. Once you wrap your head around that inversion, the rest of electrochemistry actually starts to make sense.

The Secret Identity of a Reducing Agent

A reducing agent is the "giver." In a chemical reaction, this is the substance that donates electrons to something else. Because electrons carry a negative charge, giving them away makes the donor's oxidation state go up. It becomes more positive. Or less negative. Depends on where it started.

Take magnesium. If you toss a strip of magnesium into a solution of copper sulfate, the magnesium basically bullies the copper. It shoves two electrons at the copper ions. The magnesium is the reducing agent here. It "reduces" the copper's charge from $+2$ to zero. Meanwhile, the magnesium itself gets oxidized. It’s a sacrifice. Without that electron donor, the whole reaction stalls out.

Why Oxidizing Agents are Electron Thieves

On the flip side, we have the oxidizing agent. These are the scavengers of the atomic world. They want electrons, and they want them now. Oxygen is the most famous one—hence the name—but fluorine is actually the undisputed heavyweight champion of electron theft. Fluorine is so electronegative it’ll tear electrons away from almost anything, often quite violently.

When an oxidizing agent takes an electron, its own oxidation number drops. It is being reduced. Think of it as a sponge. The sponge is the "wetting agent" for a spill, but the sponge itself gets soaked in the process.

The Real-World Stakes of Redox

This isn't just about passing a midterm. We are living in a redox world.

Consider the lithium-ion battery in your pocket. When you're using your phone, lithium atoms in the anode act as the reducing agent. They give up electrons, which flow through your phone's circuitry to do work (like lighting up this screen) before landing at the cathode. The material at the cathode acts as the oxidizing agent, happily accepting those electrons.

If we didn't have materials with specific reduction potentials, we wouldn't have portable power. Period.

The Problem with Corrosion

Rust is the dark side of this equation. Iron is a decent reducing agent, and oxygen is a fantastic oxidizing agent. When they meet in the presence of water, it's a disaster for your car's fender. The iron loses electrons to the oxygen. The iron atoms turn into iron ions ($Fe^{2+}$ and $Fe^{3+}$), which then react further to form hydrated iron(III) oxide.

That's rust.

To stop this, we use something called "sacrificial anodes." This is a brilliant bit of chemical engineering. On ships or underground pipelines, engineers bolt on blocks of zinc. Why? Because zinc is a "stronger" reducing agent than iron. The oxygen attacks the zinc instead of the steel. The zinc sacrifices itself. It’s a literal bodyguard made of metal.

Understanding the "Strength" of an Agent

Not all agents are created equal. Some are desperate to give away electrons; others would rather die than let one go. We measure this using something called standard reduction potentials ($E^0$).

- Strong Reducing Agents: Think alkali metals like Lithium or Potassium. They have huge, negative reduction potentials. They practically throw their valence electrons at passersby.

- Strong Oxidizing Agents: Think Halogens (Chlorine, Fluorine) or Permanganate ($MnO_4^-$). They have high, positive reduction potentials. They are electron-hungry.

In 1920, the legendary chemist Gilbert N. Lewis—the guy who gave us Lewis structures—really pushed the idea that these reactions are about electron pairs and movement, not just oxygen. Before him, people literally thought you needed oxygen for "oxidation." We know better now. You can have oxidation in a vacuum if you have the right agent.

Common Misconceptions That Kill Grades

People always forget that "agent" implies the cause of the action, not the recipient.

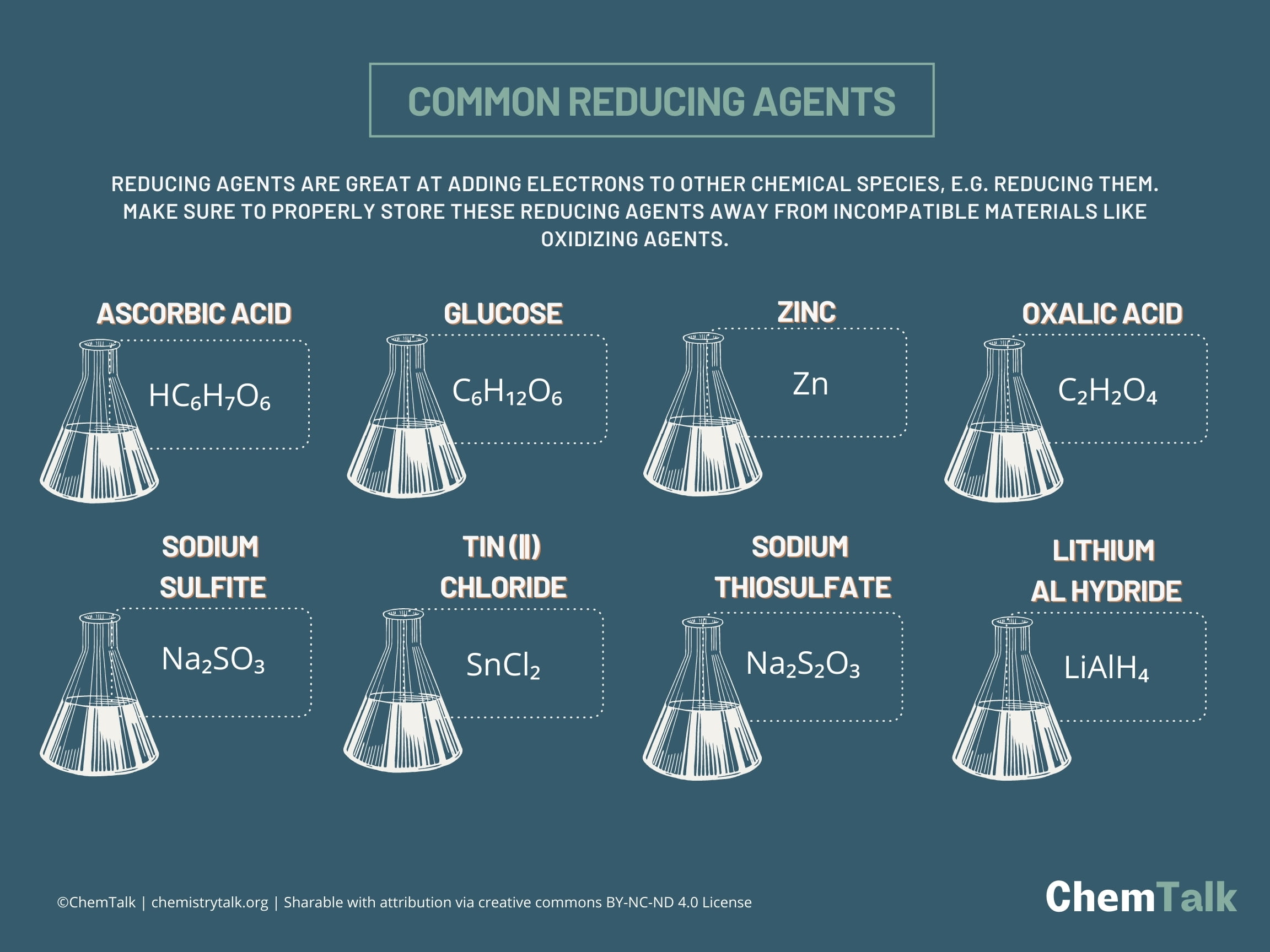

- The Charge Fallacy: Students often think a reducing agent must be negatively charged. Not true. Neutral atoms (like Zinc) are some of the best reducers.

- The "Only Oxygen" Myth: As mentioned, you don't need oxygen. Chlorine gas is a terrifyingly effective oxidizing agent.

- The Half-Reaction Trap: You cannot have one without the other. If you see a "half-reaction" where an electron is just floating away, that's a mathematical convenience. In the real world, that electron has a destination.

A Quick Cheat Sheet for the Brain

If you're struggling to keep it straight, use the "OIL RIG" acronym. Oxidation Is Loss, Reduction Is Gain (of electrons).

Then, just remember:

- The Reducing Agent causes Reduction (so it must give electrons).

- The Oxidizing Agent causes Oxidation (so it must take electrons).

Actionable Steps for Mastering Redox Chemistry

If you are trying to analyze a reaction and you’re stuck, follow this workflow. Don't skip steps.

Identify the Oxidation States first.

Before you guess who the agent is, write the oxidation number above every single atom in the equation. If you don't know the rules (like Oxygen usually being -2 and Hydrogen being +1), look them up. You can't guess this.

Look for the Change.

Find the atom whose number went up. That atom was oxidized. Therefore, the entire molecule containing that atom is the reducing agent.

Check the Balance.

If one thing went up by 2, something else better have gone down by 2 (in total). If the numbers don't match, you haven't balanced the electrons yet.

Practice with Permanganate.

If you want to test your skills, look at the reaction between Potassium Permanganate and Iron(II) sulfate in acidic solution. It’s a classic titration. The Manganese goes from $+7$ to $+2$. It’s a massive electron hog, making it a powerful oxidizing agent.

Apply it to your Life.

Next time you look at a "Vitamin C" supplement, remember that Ascorbic acid is a reducing agent. It works by "neutralizing" free radicals—which are basically oxidizing agents looking to steal electrons from your DNA. Vitamin C gets there first, gives up an electron, and saves your cells from oxidative stress.

👉 See also: The Symbol for a Photon: Why Physics Settled on the Greek Letter Gamma

Chemistry isn't just in a lab; it's the constant tug-of-war for electrons happening inside your body and your devices every second of the day.