Redd Foxx wasn't supposed to be a TV star. Honestly, the man was too "blue," too raw, and far too old-school for the sanitized living rooms of 1972 America. But then Sanford and Son happened. It didn't just break the mold; it smashed it with a literal bag of junk.

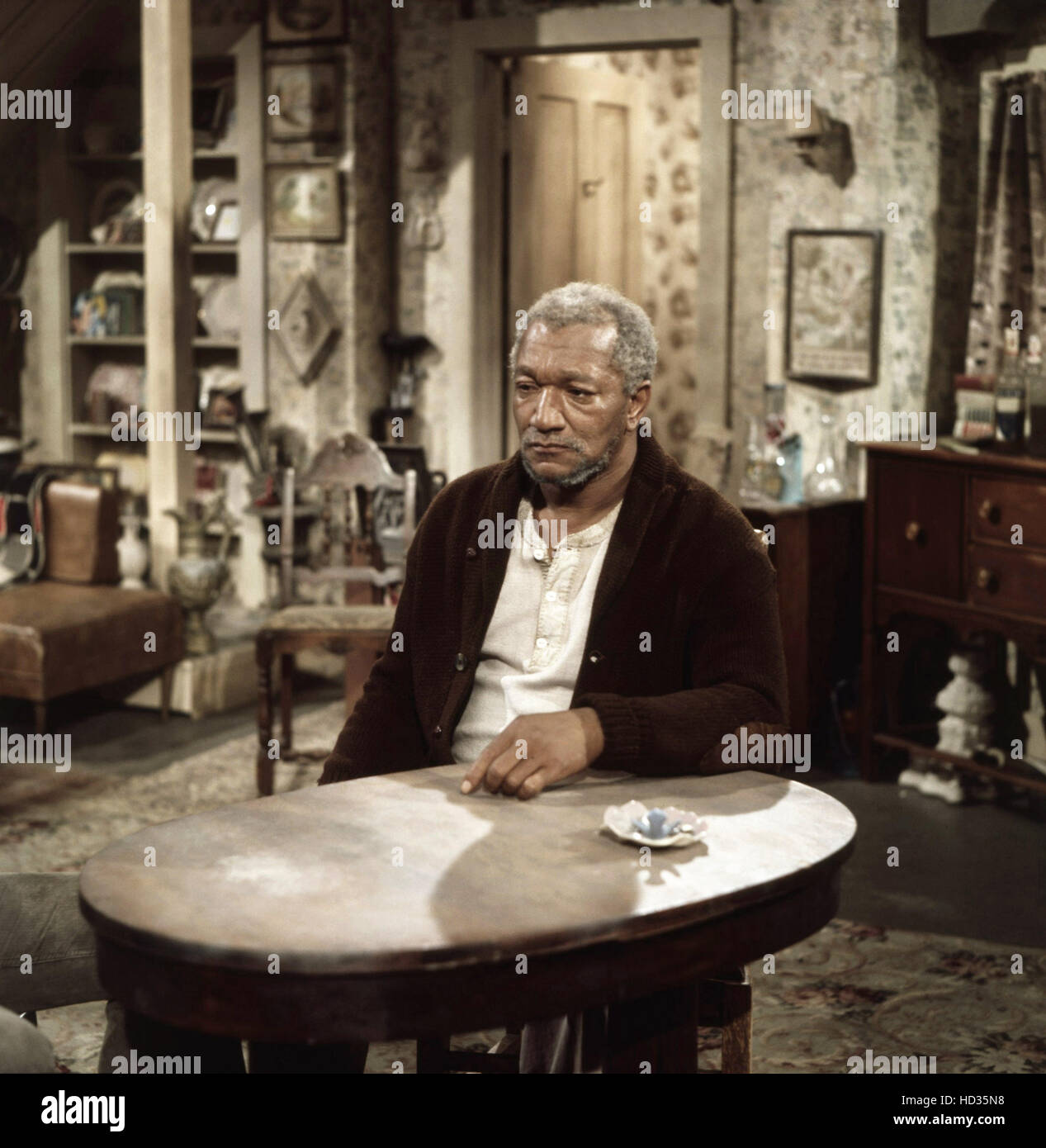

Most people remember the "Big One." They remember the fake heart attacks and the "I'm coming, Elizabeth!" routine. But if you think Redd Foxx from Sanford and Son was just a funny guy in a cardigan, you're missing the most interesting parts of the story. This wasn't just a sitcom. It was a revolution led by a man who had spent decades in the trenches of the "Chitlin' Circuit," refining an act that was—at the time—considered far too dangerous for white audiences.

The Real Fred Sanford Was a Tribute to Tragedy

Here is something you've probably never heard: Fred Sanford wasn't a character Redd Foxx just made up. The name was real. Fred Sanford was actually Redd’s older brother, who had passed away years before the show ever aired.

Think about that for a second.

Every time Redd shouted that name or looked at the "Sanford and Son" sign, he was looking at a tribute. He even insisted on the "G" in Fred G. Sanford standing for Glen, which was his brother’s middle name. It gave the show a layer of soul that most sitcoms lack. It wasn't just a job. It was personal.

Redd's real name was John Elroy Sanford. He took the "Redd" from his complexion and the "Foxx" from Jimmie Foxx, the baseball player. He was a hustler by trade. In his early New York days, he actually hung out with a young man named Malcolm Little—the man who would eventually become Malcolm X. They were both "Reds" back then, dodging the law and trying to survive.

Breaking the "Blue" Barrier

Before he was the king of Friday nights on NBC, Redd Foxx was the "King of the Party Records."

He recorded over 50 of them. These weren't the clean, observational jokes you'd hear on The Ed Sullivan Show. They were raunchy. They were "blue." People used to hide those albums under their coats when they walked out of record stores. He sold 15 million copies of this stuff while the mainstream media didn't even know his name.

When Sanford and Son creator Norman Lear approached him, it was a massive gamble. You had this R-rated comedian being asked to play a 65-year-old junk dealer. The funny part? Redd was only 48 when the show started. He had to wear heavy makeup and walk with that famous bowlegged shuffle just to look the part.

Why Sanford and Son Still Matters Today

You can't talk about Redd Foxx from Sanford and Son without talking about how he used his power. Most stars get a hit show and pull the ladder up behind them. Redd did the opposite.

He looked at the cast list and saw a lack of Black talent. So, he started making demands. He brought in his old friends from the Chitlin' Circuit—people the industry had ignored for decades.

- LaWanda Page (Aunt Esther) was a childhood friend and a former fire-eater. The producers didn't want her. Redd told them: "No LaWanda, no Redd."

- Don Bexley (Bubba) and Slappy White were his old comedy partners.

- He even helped push for Richard Pryor and Paul Mooney to get writing credits on the show.

He turned a 30-minute sitcom into a Trojan horse for Black excellence. He was demanding. He was difficult. He once walked off the set for months because he wanted a dressing room with a window. People called him a "diva," but Redd saw it as a matter of respect. He knew his worth. He knew the show was nothing without that specific, gritty chemistry between him and Demond Wilson.

The Comedy of Conflict

The show was basically an Americanized version of a British hit called Steptoe and Son. But Redd made it uniquely American. He played Fred as a man who was constantly "conning" his way through a world that had tried to keep him down.

It was a show about a father and son who loved each other but couldn't stand each other. That’s universal. But it was also about a Black man in Watts just trying to keep his head above water.

The Tragic Irony of "The Big One"

Life is cruel sometimes.

In 1991, Redd was working on a new show called The Royal Family. During a rehearsal, he collapsed. He clutched his chest. He fell to the floor.

💡 You might also like: Where Can I Watch Pearson: What Most People Get Wrong

The crew laughed.

They thought it was the bit. They thought he was doing the "Elizabeth, I'm coming to join you" routine. For several minutes, everyone stood around waiting for him to get up and deliver the punchline. He never did. He died of a heart attack at 68, literally "crying wolf" one too many times in the eyes of the public.

He died broke, too. The IRS had been hounding him for years. In 1989, they actually showed up at his house and took everything—his cars, his jewelry, even the bed he slept in. It was a humiliating end for a man who had built a literal empire.

A Legacy That Won't Quit

Even with the tragic end and the tax drama, Redd Foxx from Sanford and Son remains the blueprint.

Every time you see a comedian like Eddie Murphy (who actually paid for Redd’s funeral because he respected him so much) or Chris Rock, you’re seeing the DNA of Redd Foxx. He proved that you could be "unfiltered" and still be a superstar. He showed that "Black comedy" wasn't a niche—it was the main event.

If you want to truly appreciate his work, don't just watch the clips of him clutching his chest. Look at the way he looked at Lamont. Look at the timing of his insults. He was a master of the "long game" joke.

Next Steps to Explore the Legend:

📖 Related: April Ludgate: Why This Parks and Rec Character Still Matters

To get the full picture of Redd's impact, you should check out the 1989 film Harlem Nights. It’s the only time you get to see the three generations of comedy royalty—Redd Foxx, Richard Pryor, and Eddie Murphy—on screen together. It’s essentially a passing of the torch. Also, tracking down some of his original Dooto Records "party albums" (if you can handle the language) provides the necessary context for why his transition to a network sitcom was such a shock to the system in the 70s.