Let's be real. Most people trying to drop a few pounds end up staring at a glowing screen, wondering why a random algorithm says they should eat exactly 1,200 calories. It feels scientific. It looks precise. But honestly? It’s often a complete guess. Determining the recommended calories for weight loss isn't about hitting a magic number that some influencer posted on Instagram. It’s actually a moving target influenced by everything from your muscle mass to how much you fidget while answering emails.

You've probably heard the "3,500 calorie rule." The idea is that if you cut 500 calories a day, you'll lose exactly one pound a week. It’s a classic. It’s also wildly oversimplified. Max Wishnofsky came up with that math back in 1958, and while it’s a decent starting point, it doesn't account for how the human body fights back when it thinks it's starving.

Your body is smart.

When you slash calories, your metabolism doesn't just stay put. It adapts. This is what researchers call adaptive thermogenesis. Basically, your body gets more efficient at using energy because it’s trying to keep you alive. So, that 1,500-calorie "perfect" plan you found? It might work for three weeks and then hit a wall. That's not a failure of will. It's biology.

💡 You might also like: What Color Is Your Brain? The Surprising Truth About What’s Inside Your Head

The Math Behind Recommended Calories for Weight Loss

To actually find your number, you have to start with your Total Daily Energy Expenditure (TDEE). This is the sum of everything your body burns in 24 hours. It’s not just the treadmill. It’s your heart beating, your lungs breathing, and your brain processing these words.

Most of this—about 60% to 75%—is your Basal Metabolic Rate (BMR).

If you want to get technical, experts often use the Mifflin-St Jeor equation. It’s currently considered the most accurate for most people. For a man, the formula looks like: $10 \times \text{weight (kg)} + 6.25 \times \text{height (cm)} - 5 \times \text{age (y)} + 5$. For women, it’s $10 \times \text{weight (kg)} + 6.25 \times \text{height (cm)} - 5 \times \text{age (y)} - 161$.

After you find that BMR, you multiply it by an activity factor.

- Sedentary (office job, no exercise): 1.2

- Lightly active (light exercise 1–3 days/week): 1.375

- Moderately active (moderate exercise 3–5 days/week): 1.55

- Very active (hard exercise 6–7 days/week): 1.725

Here is the problem: humans are terrible at estimating their activity. We think a 30-minute walk burns 500 calories. It doesn't. It’s usually closer to 150. This is why people get frustrated. They think they’re in a deficit, but they’re actually eating at maintenance because they overcalculated their "active" status.

Why the 1,200 Calorie Myth Won't Die

The "1,200 calorie diet" has become a sort of gold standard in the weight loss world, especially for women. It's almost a meme at this point. But for many, 1,200 calories is lower than their BMR. That means you aren't even eating enough to support your basic organ function.

🔗 Read more: Is a Resting Pulse Rate 85 Actually Normal? What the Data Really Says

When you go that low, things get weird. You get "brain fog." Your hair might thin. You get cold easily. Most importantly, you lose muscle. Muscle is metabolically active tissue; it burns more calories at rest than fat does. If you starve yourself, your body eats its own muscle for energy. Now, your BMR drops. You’ve successfully made it harder to lose weight in the future.

It’s a trap.

A more sustainable recommended calories for weight loss approach is a modest deficit of 10% to 20% below your maintenance. If your maintenance is 2,500, try 2,000 or 2,200. It’s slower. It’s less "exciting" than losing 5 pounds in a week of cabbage soup dieting. But it's the only way to keep the weight off without ruining your relationship with food.

NEAT: The Secret Variable

Exercise is great for your heart, but it’s actually a small part of the calorie equation. Enter NEAT: Non-Exercise Activity Thermogenesis. This is the energy spent on everything we do that isn't sleeping, eating, or sports-like exercise.

Walking to the car.

Pacing while on the phone.

Cleaning the kitchen.

Even fidgeting.

Two people of the same height and weight can have a TDEE difference of 500 to 1,000 calories just based on NEAT. If you sit at a desk for 8 hours and then do a "hard" 45-minute workout, you might still be burning fewer calories than a waiter who stands all day but never goes to the gym.

This is why "calories in, calories out" (CICO) is true, but also incredibly complex. You can't just look at the gym log. You have to look at the whole day. If your recommended calories for weight loss feel too low to be sustainable, the answer might not be eating less, but moving more in small, "non-exercise" ways.

Protein and the Thermic Effect of Food

Not all calories are processed the same way. This isn't "bro-science"—it's the Thermic Effect of Food (TEF). Your body actually uses energy to digest food.

👉 See also: How Much Vitamin B12 Per Day Mcg: The Real Truth Behind Those Supplement Labels

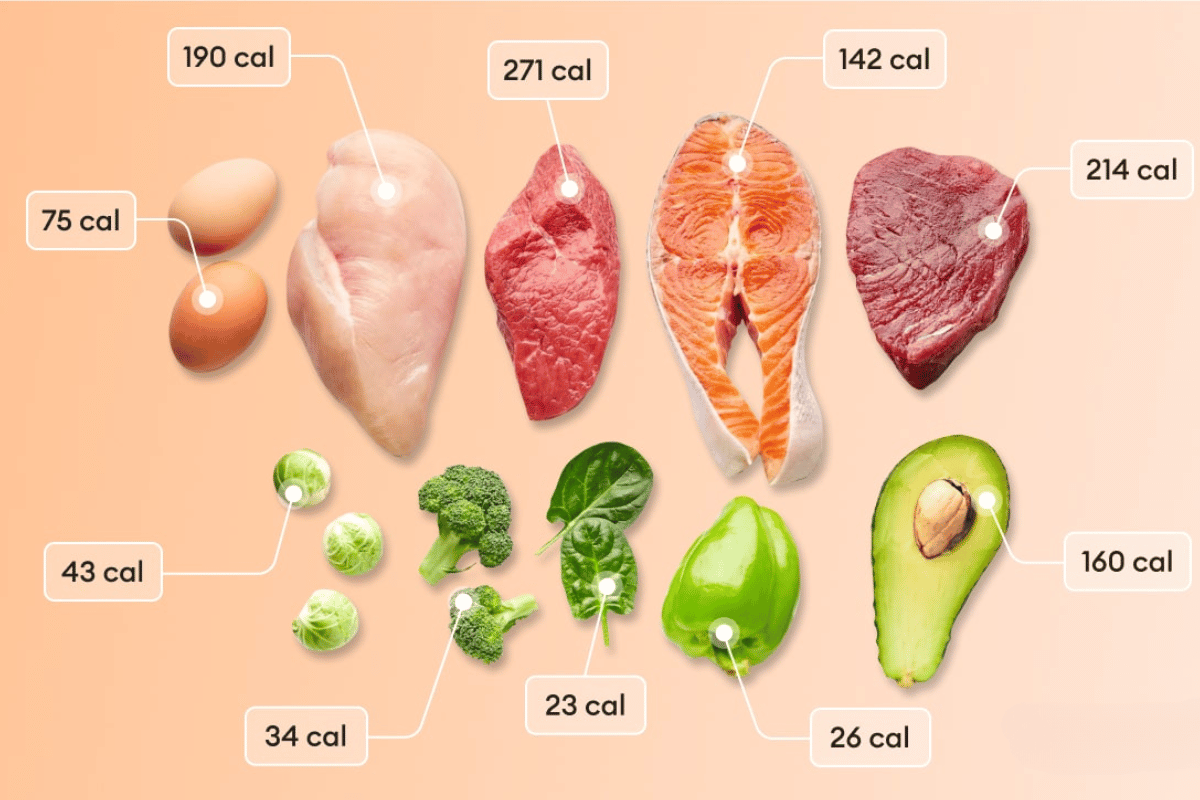

Protein has a high TEF. About 20% to 30% of the calories in protein are burned just during digestion. Compare that to fats (0–3%) or carbohydrates (5–10%). If you eat 100 calories of chicken breast, your body only "keeps" about 70 to 80 of them. If you eat 100 calories of butter, it keeps almost all of them.

This is why high-protein diets are so effective for weight loss. They keep you full, they protect your muscle mass, and they "waste" more energy during digestion. If you’re struggling to stay within your recommended calories for weight loss, bumping your protein intake to 0.8g or 1g per pound of goal body weight can be a game changer. It’s hard to overeat on chicken and broccoli. It’s very easy to overeat on pasta and olive oil.

Real-World Nuance: The "Stall"

So, you’ve calculated your numbers. You’re tracking everything. You’ve been at it for a month, and the scale hasn't moved for ten days.

First, don't panic.

Weight loss isn't linear. It looks like a jagged mountain range on a graph. You might be holding onto water because of a salty meal, a tough workout (muscles hold water to repair), or hormonal shifts. For women, the menstrual cycle can cause weight fluctuations of 3 to 5 pounds in a single week. That’s not fat. It’s just fluid.

Also, check your tracking accuracy. "A tablespoon of peanut butter" is almost never actually a tablespoon when people eyeball it. It’s usually two. That’s an extra 100 calories right there. If you do that with three or four items a day, your deficit has vanished.

If you’ve truly plateaued for more than three or four weeks, it might be time for a "diet break." Research, like the MATADOR study (Minimizing Adaptive Thermogenesis and Deactivating Obesity Rebound), suggests that taking two weeks off from your deficit—eating at maintenance—can help reset some of those metabolic adaptations. It sounds counterintuitive, but eating more for a brief period can sometimes kickstart weight loss again.

Quality vs. Quantity: Does it Matter?

Can you lose weight eating only Twinkies if you stay under your calorie goal? Yes. Professor Mark Haub at Kansas State University actually did this. He lost 27 pounds in 10 weeks eating Oreos, Doritos, and sugary cereals.

But he felt like garbage.

While the recommended calories for weight loss are the primary driver of fat loss, the source of those calories dictates your health, your hunger levels, and your ability to actually stick to the plan. Processed foods are designed to be "hyper-palatable." They bypass your "I'm full" signals. Whole foods—potatoes, eggs, steak, fruit—do the opposite.

Actionable Steps to Finding Your Number

Stop looking for a perfect answer and start experimenting. Use these steps to find a sustainable rhythm:

- Track your current intake for 7 days. Don't change anything. Just see what you’re actually eating. If your weight is stable, that's your maintenance.

- Subtract 250 to 500 calories. This is your starting point. It's much more accurate than a calculator because it's based on your actual life.

- Prioritize protein. Aim for at least 25-30 grams per meal. This manages hunger better than anything else.

- Monitor "non-scale victories." How do your clothes fit? How is your energy? Sometimes the scale stays the same because you're losing fat but gaining muscle (recomposition).

- Adjust every 5-10 pounds. As you lose weight, your body requires less energy to move. You will eventually need to lower your calories slightly or increase activity to keep the progress going.

The "right" amount of calories is the highest number you can eat while still seeing progress. Why suffer on 1,200 if you can lose weight on 1,800? Start high and only go lower if you absolutely have to. Sustainable weight loss is a marathon, and you can't run a marathon if you're out of fuel.