Disease doesn't wait. It doesn't care about borders, and honestly, it doesn't care if we're "tired" of hearing about public health after the last few years. While the big headlines have faded, the truth is that recent epidemics in the world are moving faster than they used to. As of early 2026, we're seeing a weird, almost frantic shifting of viruses and bacteria into places they really shouldn't be.

Take Marburg virus. For a long time, it was this ultra-rare thing you only heard about in specialized medical journals. Then, late last year in 2025, Ethiopia confirmed its first-ever outbreak. By January 2026, the Ethiopian Ministry of Health reported 14 confirmed cases and nine deaths. That's a massive deal. It’s a hemorrhagic fever, basically a cousin of Ebola, and it showed up in Jinka, a town near the border with South Sudan.

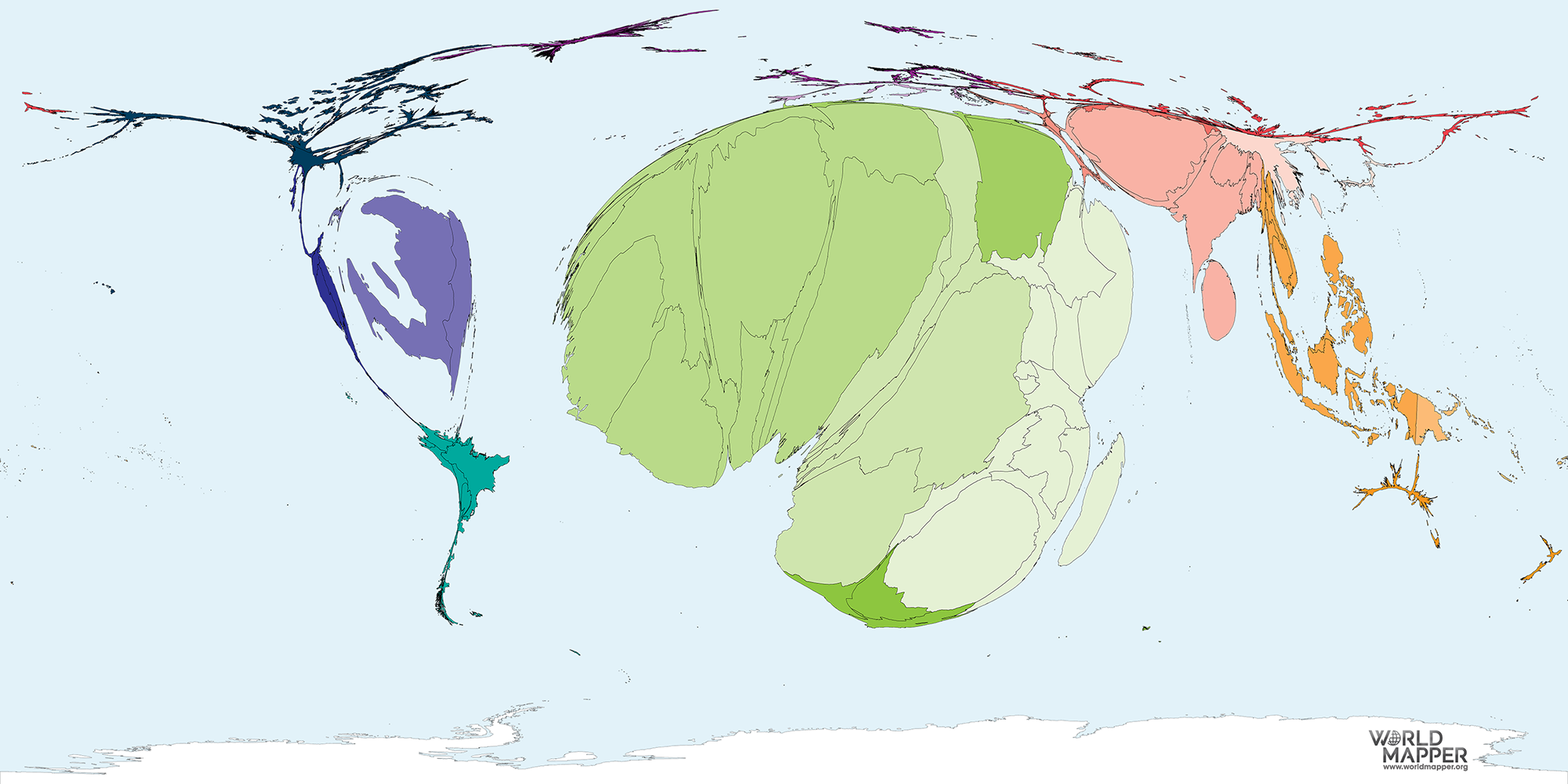

Why does this matter? Because it shows the map is changing.

Why Recent Epidemics in the World are Getting Weirder

It isn't just one "big bad" virus anymore. It’s a messy soup of different threats. We have climate change pushing mosquitoes into new territories and conflict zones making it impossible to vaccinate kids. It's a perfect storm.

👉 See also: Vitamin D3: What Most People Get Wrong About the Sunshine Hormone

The Mpox Situation Isn't Over

You probably remember the mpox (formerly monkeypox) surge from a couple of years ago. Most people think it went away. It didn't. In fact, on January 10, 2026, health authorities in Mallorca, Spain, reported an outbreak of Mpox Clade I. This is the more virulent version that everyone was worried about. Just days later, Germany confirmed that Clade Ib is now spreading locally in Berlin among people who haven't even traveled recently.

This isn't just a "travelers' disease" anymore. It's settling in.

The Bird Flu "Crossover"

In 2024, the H5N1 avian influenza virus made a jump that sent scientists into a bit of a panic: it hit dairy cattle in the U.S. By now, in early 2026, infectious disease experts like those at Gavi are watching it like hawks. The concern is simple—if it learns to jump efficiently from human to human, we’re looking at a brand-new pandemic. Currently, the CDC is tracking several cow-to-human transmissions, but we're still in that "wait and see" period that feels way too much like early 2020.

✨ Don't miss: 10 minute arm exercises: Why you’re probably overcomplicating your upper body routine

The Diseases We Thought We Beat

Honestly, it’s frustrating. We have vaccines for things like measles and pertussis (whooping cough), yet they’re surging. In the United States alone, nearly 29,000 cases of pertussis were reported as we headed into 2026.

Measles is even worse. It's arguably the most contagious virus on the planet. Because of a mix of vaccine hesitancy and pandemic-era disruptions to childhood checkups, it’s tearing through communities in Argentina, Morocco, and parts of the U.S. Morocco saw over 25,000 suspected cases by mid-2025. You need about 95% community immunity to stop measles. We’re just not there right now.

Cholera: The Crisis Multiplier

If you want to know where the world is hurting the most, look at the cholera maps. This isn't just a "dirty water" problem; it's a war problem. Between January and August 2025, the WHO estimated over 409,000 cases globally.

🔗 Read more: Yoga Poses Lying on Back: Why Your Spine Honestly Needs Them Every Single Day

- Afghanistan and Yemen: Over 233,000 cases of cholera and acute watery diarrhea.

- Sudan: More than 52,000 cases recorded as of late last year.

- Haiti: Still struggling with the aftermath of historical introductions and infrastructure collapse.

Cholera is basically a marker of human suffering. When the pipes break and the hospitals are bombed, cholera moves in. It's that simple.

The Mosquito's New Map

Mosquitoes are moving north. Fast. Dengue fever, which used to be something you only worried about in the tropics, is now a reality in the continental United States. In 2025, the U.S. saw over 2,500 locally acquired cases.

And then there's Chikungunya.

Warmer weather in Europe has allowed the Aedes albopictus mosquito to set up shop in 16 different European countries. By the end of August 2025, the continent had already dealt with 27 separate outbreaks. It's weird to think about, but the "tropical disease" label is basically becoming obsolete.

What This Means for You (Actionable Steps)

It’s easy to feel overwhelmed by all this, but you actually have more control than you think. Public health isn't just something that happens to other people; it's a set of habits.

1. Check Your Records

Don't assume you're protected. If you can't remember your last Tdap (tetanus, diphtheria, and pertussis) booster, call your doctor. Same goes for the MMR (measles, mumps, rubella) vaccine. With pertussis cases at a 10-year high, that booster isn't just for "new parents" anymore.

2. Watch the Travel Advisories

Before you book that flight to Ethiopia or even parts of Europe, check the CDC’s Level 1 and 2 notices. They aren't telling you not to go, but they are giving you a heads-up. For example, if you're headed to an area with an active Marburg or Ebola threat, staying away from caves or bat habitats is a literal lifesaver.

3. Environmental Defense

If you live in a region where Dengue or Chikungunya is appearing, bug spray is no longer optional for hiking. Use EPA-registered repellents and empty any standing water in your yard. Those three inches of water in a forgotten flowerpot can hatch thousands of mosquitoes.

4. The Fever Rule

If you develop an "acute febrile illness"—basically a sudden, high fever with no clear cause—after traveling, tell your doctor exactly where you were. Don't leave out that three-hour layover or the rural market you visited. Doctors can't test for what they don't know to look for.

The landscape of recent epidemics in the world is clearly shifting. We’re moving into an era where "local" outbreaks become global news in a matter of hours. Staying informed isn't about being scared; it's about being ready for a world that is much more interconnected than our health systems sometimes realize.