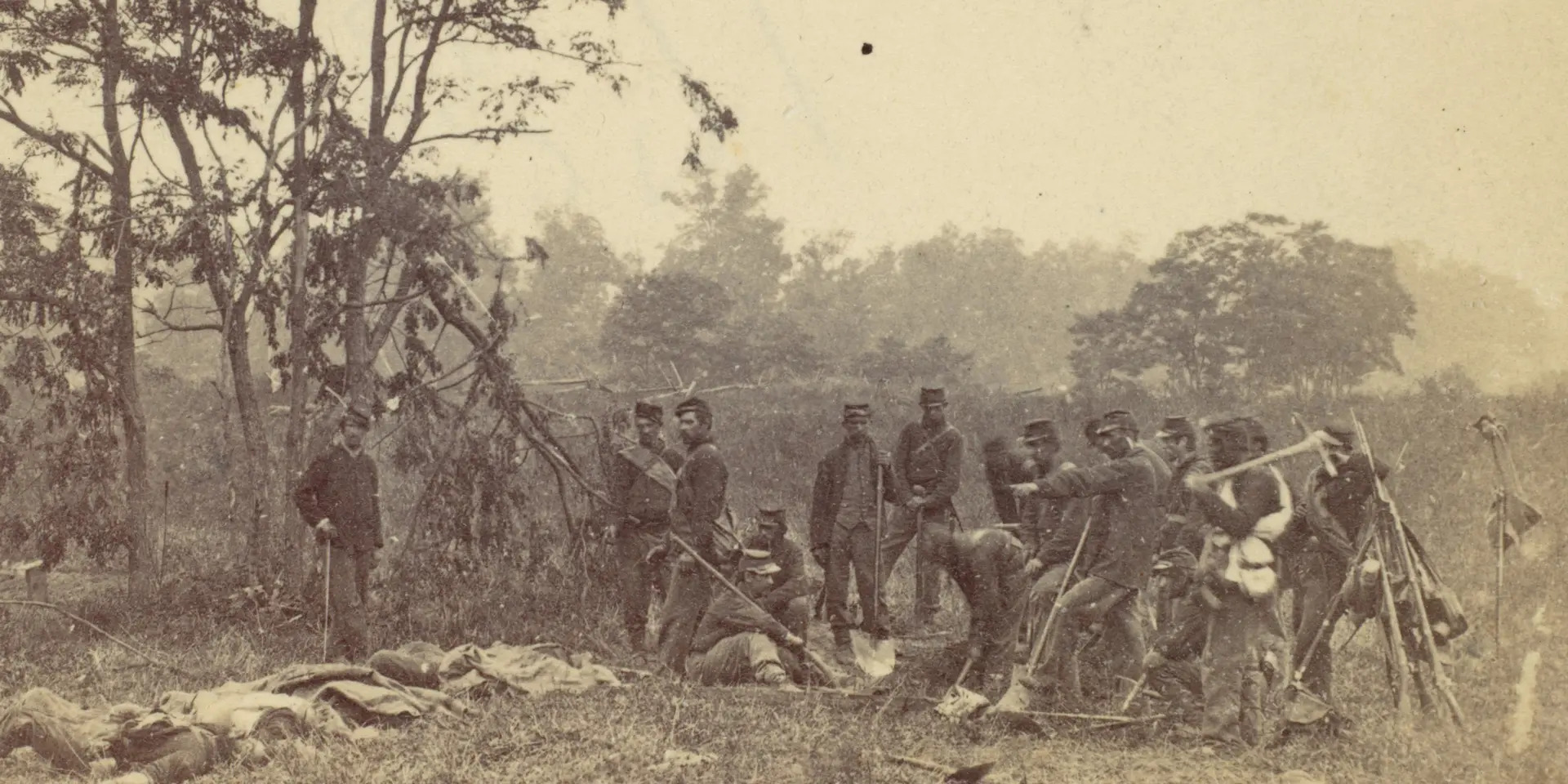

If you close your eyes and think about the American Civil War, you probably see a grainy, sepia-toned world where everyone stands perfectly still and looks incredibly grumpy. It feels like ancient history. But when you actually look at real pictures of the Civil War, that distance kinda disappears. You realize these weren't just "historical figures." They were teenagers with bad haircuts, tired dads missing their families, and people who were frankly terrified.

Photography was brand new. Basically, the Civil War was the first major conflict captured by the lens in a way that regular people could see. Before this, war was something you read about in the papers or saw in romanticized oil paintings where the generals looked like gods. Suddenly, through the work of people like Mathew Brady and Alexander Gardner, the public saw the mud. They saw the bloated horses. They saw the reality of a country tearing itself apart.

Why Real Pictures of the Civil War Look So Weirdly Still

Have you ever wondered why nobody is smiling in these photos? It wasn't just because life sucked in the 1860s, though it definitely did. It was a technical limitation. The "wet-plate" collodion process was a total nightmare to manage. A photographer had to coat a glass plate with chemicals, rush it into the camera while it was still wet, take the shot, and develop it immediately.

Exposure times could last anywhere from five to thirty seconds. If you blinked, you were a blur. If you sneezed, the photo was ruined. This is why you don't see "action shots" of Pickett’s Charge or the chaos at Antietam. Every single one of those real pictures of the Civil War featuring soldiers in the field was taken before or after the shooting started.

Imagine carrying a literal glass laboratory into a war zone. Photographers traveled in wagons they called "What-is-it?" wagons because they looked so strange. They were targets. They were in the way. Yet, they captured details that even the best historians struggle to describe in words. You can see the individual stitches on a Union private’s frock coat or the exact way the dirt caked onto a Confederate’s bare feet.

The Controversy of the "Staged" Photos

Here is something that kinda ruins the "pure" history of it all: some of the most famous photos were faked. Or, well, "composed" is the nicer word.

Take the famous "Home of a Rebel Sharpshooter" at Gettysburg. It shows a dead Confederate soldier in a rocky crevice called Devil’s Den. For decades, people held this up as the ultimate raw image of the war. But later research by historians like William Frassanito proved that Gardner and his assistants actually moved the body. They dragged the poor guy about forty yards, propped his head up, and leaned a rifle against the rocks to make it look more dramatic.

💡 You might also like: Blanket Primary Explained: Why This Voting System Is So Controversial

Does that make it less "real"? Honestly, it depends on who you ask. At the time, photographers saw themselves more as artists or dramatists than objective journalists. They wanted to convey the feeling of the slaughter, even if the literal arrangement wasn't 100% accurate.

Beyond the Battlefield: The Faces of the Enslaved

We talk a lot about the soldiers, but some of the most impactful real pictures of the Civil War aren't of men in uniform. They are of the people the war was actually about.

The photograph of "Gordon" (also known as "Whipped Peter") is probably one of the most important images in American history. It shows a man who escaped slavery and reached Union lines in 1863. His back is a map of keloid scars from repeated whippings. When that photo was distributed as a "carte de visite" (basically a 19th-century trading card), it did more to turn Northern public opinion against slavery than almost any speech ever could. It was proof. You couldn't argue with a photograph.

The Technology That Changed Everything

The Civil War happened right at the intersection of the Industrial Revolution and the birth of media.

- Tintypes: These were cheap and durable. Soldiers loved them because you could drop one in a pocket and mail it home without it shattering.

- Stereographs: These were the 1860s version of VR. Two nearly identical photos were mounted on a card, and when viewed through a special device, the image popped into 3D.

- Albumen Prints: This used egg whites to bind chemicals to paper. Millions of eggs were used every year just to print photos of the war.

Think about that. The visual record of the bloodiest conflict in U.S. history was literally held together by egg whites. It’s a weirdly fragile way to document such a massive event.

What Most People Get Wrong About the "Brady" Photos

If you look at the Library of Congress archives, thousands of images are credited to Mathew Brady. But Brady actually didn't take many of them himself. He was more like a studio boss. He hired guys like Timothy O'Sullivan and Alexander Gardner to go into the mud while he stayed in his fancy studio in Washington D.C. or New York.

📖 Related: Asiana Flight 214: What Really Happened During the South Korean Air Crash in San Francisco

Eventually, his staff got annoyed that he was taking all the credit. Gardner eventually quit and started his own business, which is why we have such a massive, diverse record of the war. If it hadn't been for that ego clash, we might have half the images we do today.

The Haunting Silence of the Dead

When Brady opened an exhibition in New York called "The Dead of Antietam" in 1862, it shocked the city. The New York Times wrote that Brady had "brought home to us the terrible reality and earnestness of war." For the first time, people saw that soldiers didn't die in heroic poses. They died in heaps. They died in trenches. They died looking small and lonely.

How to Spot a Fake vs. a Real Original

If you're ever at an antique mall or browsing eBay for real pictures of the Civil War, you have to be careful. Modern "repros" are everywhere.

First, check the material. If it’s on paper that feels like a modern glossy photo, it’s a fake. Original 19th-century paper has a specific texture; it's thin and often mounted on heavy cardstock.

Look for "foxing." Those are the little brown spots that appear on old paper due to fungal growth or iron oxidation. It's hard to fake that naturally. Also, check the depth. Original daguerreotypes or ambrotypes have a "mirrored" quality where the image seems to float inside the glass or metal. If it looks flat and printed, it probably is.

The Lost Photos We’ll Never See

It’s heartbreaking to think about, but we’ve probably lost more Civil War photos than we’ve saved.

👉 See also: 2024 Presidential Election Map Live: What Most People Get Wrong

In the years after the war, glass plates were often sold to gardeners. Why? Because the glass was high-quality. People used them to build greenhouses. Over time, the sun literally baked the images off the glass until they were just clear panes again. Entire battles, faces of thousands of men, and moments of history were wiped clean just so someone could grow better tomatoes in 1880.

Why This Still Matters in 2026

We live in a world of AI-generated images and deepfakes. You can ask a computer to show you "a soldier at Gettysburg," and it will give you something that looks perfect. But it isn't real.

The power of real pictures of the Civil War lies in their imperfections. The chemical swirls in the corner of the plate. The thumbprint of the photographer who was shaking because he was standing in a graveyard. The blurred tail of a horse that wouldn't stand still.

These images are a tether to the truth. They remind us that the people who lived through 1861-1865 weren't characters in a book. They were as real as you are. They breathed the same air, felt the same sun, and suffered through a conflict that still defines much of American life today.

How to Explore the Archives Yourself

You don't need to be a scholar to see these. Most of the best stuff is digitized and free.

- The Library of Congress: Their "Civil War Glass Negatives and Related Prints" collection is the gold standard. You can zoom in so far you can see the dirt under a general's fingernails.

- The National Archives: Great for more "official" military documentation and photos of forts and naval ships.

- The Gilder Lehrman Institute: They have incredible personal collections, including letters that often accompanied these photos.

- The Center for Civil War Photography: This group does amazing work identifying the "where" and "when" of mystery photos using modern mapping tech.

The best way to "read" these photos is to look past the main subject. Look at the background. Look at the trash on the ground, the chopped-down trees, and the expressions of the people watching from the windows. That’s where the real history is hiding.

If you want to dive deeper into the visual history of the 1860s, start by searching the Library of Congress digital portal for specific regiments from your home state. Seeing the faces of the people who lived in your town 160 years ago changes the way you look at your own backyard. You can even use modern tools to overlay these historical images onto Google Street View to see exactly where a photographer stood in 1863 compared to what stands there now.