It is a weird feeling to look at a face from 1863. You see the grit in the pores, the dirt under the fingernails, and that thousand-yard stare that hasn't changed in over 160 years. Most people think they’ve seen real photos of the civil war because they caught a glimpse of a blurry Abraham Lincoln in a history book. But there is a massive difference between a "historical artifact" and a high-resolution window into a dead world.

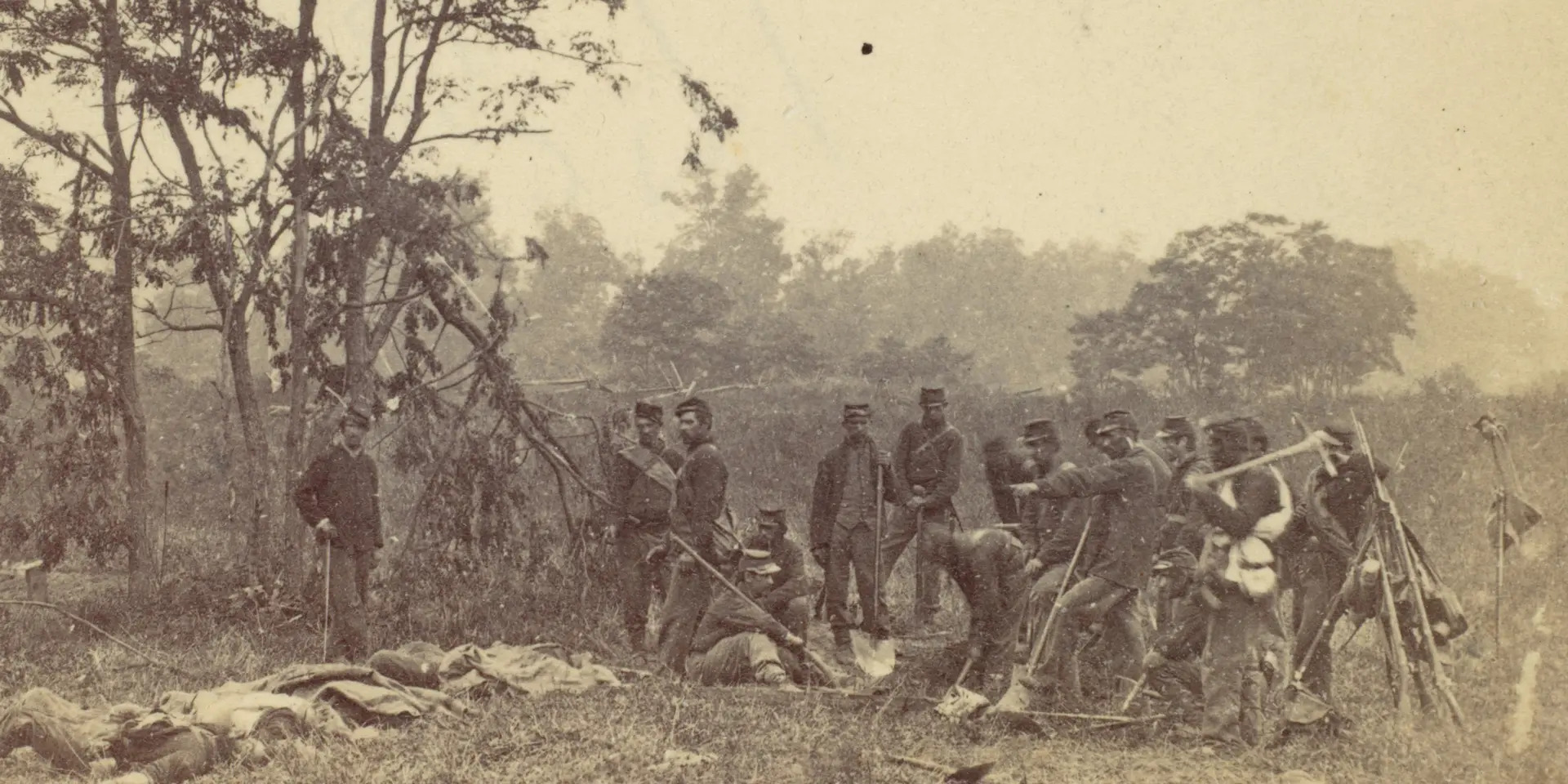

The Civil War was the first major conflict to be truly documented by the camera. It changed everything. Before this, war was oil paintings and heroic poses. Afterward? It was mud. It was bloated horses. It was young men leaning against oak trees, looking like they just wanted to go home.

The Glass Plate Revolution

Back then, you couldn't just "snap" a photo. If you wanted to capture real photos of the civil war, you had to haul a literal wagon—often called a "what-is-it" wagon by confused soldiers—filled with volatile chemicals and heavy glass plates. This was the wet-plate collodion process.

Basically, a photographer like Timothy O'Sullivan or Alexander Gardner had to coat a glass plate in chemicals, rush it into the camera while it was still wet, expose it for several seconds, and then develop it immediately. If the plate dried out, the image was ruined. It was dangerous, back-breaking work performed in the middle of active war zones.

This is why you don't see "action shots" in the way we think of them today. You won't find a photo of a bayonet charge or a cannon firing in mid-air. The shutter speeds were too slow. If someone moved, they became a ghost. That’s why the most haunting images are the ones of the aftermath. The stillness. The silence of the battlefield at Antietam or Gettysburg.

Matthew Brady: The Man, The Myth, The Debt

Everyone mentions Matthew Brady when talking about these images. He was the "father of photojournalism," sure, but he actually didn't take most of the photos credited to him. Brady had failing eyesight. He was more of a manager. He hired guys like Gardner and George N. Barnard to go into the field.

Brady spent a fortune—about $100,000 of his own money—to document the war. He honestly thought the government would buy his archive for a massive sum once the fighting stopped. They didn't. He ended up dying broke in a hospital ward, which is a pretty grim post-script for the man who preserved the visual soul of the nation.

👉 See also: Finding the University of Arizona Address: It Is Not as Simple as You Think

Why Some Photos Look "Off"

We have to talk about the ethics of 19th-century photography. Alexander Gardner's famous shot, "Home of a Rebel Sharpshooter," is one of the most iconic real photos of the civil war. It shows a dead Confederate soldier in a stone barricade at Gettysburg.

Research later proved Gardner moved the body.

He dragged the poor kid about 40 yards to a more "scenic" spot and propped a rifle against the wall to make a better composition. Does that make it "fake"? Not exactly. The soldier was real. The death was real. But the narrative was constructed. This happened more than we’d like to admit. Photographers were trying to tell a story of tragedy, and sometimes they felt the raw reality wasn't "artistic" enough.

The Detail You Can Only See in High-Res

If you go to the Library of Congress website and download the original TIFF files of these glass plates, the detail will blow your mind. You can zoom in on a group of Union officers sitting outside a tent and see the brand of the tobacco tins on the table. You can see the specific weave of the wool in their coats.

This clarity created a visceral shock for people back home. In 1862, Brady held an exhibition in New York called "The Dead of Antietam." For the first time, civilians saw what war actually looked like without the filter of a painter's brush. The New York Times wrote that Brady had "brought home to us the terrible reality and earnestness of war." They said he might as well have laid the bodies right on the sidewalk.

The Forgotten Faces: Beyond the Generals

We’ve all seen Lee and Grant. But the most compelling real photos of the civil war are the "ID" photos—the tintypes and ambrotypes kept in small brass cases. These were the selfies of the 1860s.

✨ Don't miss: The Recipe With Boiled Eggs That Actually Makes Breakfast Interesting Again

- Soldiers would pose with their best friends, often holding hands or leaning on each other.

- They’d show off their brand-new revolvers or Bowie knives, looking terrifyingly young.

- African American soldiers, like those in the 54th Massachusetts, posed with a fierce sense of dignity that challenged every racial stereotype of the era.

There’s a photo of a man named Gordon (often called "Whipped Peter") that changed the course of the war. It shows his back, covered in a "lattice" of keloid scars from years of abuse under slavery. When that photo was circulated as a "carte-de-visite," it became an undeniable piece of evidence for the abolitionist cause. That's the power of the camera. It doesn't just record; it convicts.

The Logistics of Death

Most people don't realize that photography was a business. After a battle, photographers would scramble to get to the field before the burial crews. They needed the bodies for the shots. Once the dead were in the ground, the "commercial" value of the battlefield plummeted.

It sounds morbid because it was.

These photographers were entrepreneurs. They sold stereo cards—double images that looked 3D when viewed through a special device—to families who wanted to "experience" the war from their parlors. It was the Victorian version of a VR headset.

What Happened to the Plates?

It’s a miracle we have as many real photos of the civil war as we do. Many glass negatives were sold after the war to gardeners. Why? Because the glass was high quality. In the lean years of the late 19th century, people used them to build greenhouses.

Think about that. For years, the sun shone through the ghostly faces of dead soldiers to grow lettuce and tomatoes.

🔗 Read more: Finding the Right Words: Quotes About Sons That Actually Mean Something

The heat and light eventually burnt the images off the glass, erasing thousands of unique historical records forever. The ones that survived did so mostly by luck, tucked away in attics or forgotten in government crates.

How to Spot a Genuine Civil War Photo

If you're looking at "newly discovered" images online, be careful. There’s a lot of "Civil War style" photography out there today. Reenactors are very good at what they do.

- Check the eyes. Genuine 19th-century subjects have a specific look because they had to hold still for so long. There is a tension in the jaw and a stillness in the pupils that is hard to fake.

- Look for the "collar." Most studio portraits used a hidden iron stand called a "head rest" to keep the subject's head still. Sometimes you can see the base of the metal stand peeking out from behind their boots.

- The edges matter. Real glass plate negatives often have "slop" or chemical staining around the borders. If the image is perfectly clean all the way to the edge, it’s probably a modern crop or a reproduction.

Practical Steps for History Buffs

If you want to go beyond the surface level of real photos of the civil war, you shouldn't just look at Google Images. You need the raw stuff.

Go to the Library of Congress Digital Collections. Search for "Civil War Glass Negatives." When you find one you like, don't just look at the thumbnail. Download the largest file size available. Zoom into the background. Look at the trees, the horses, and the trash on the ground. You will find things the photographer didn't even know they were capturing.

Visit the National Museum of Civil War Medicine in Frederick, Maryland. They have incredible insights into how photography was used to document wounds and medical progress. It’s grisly, but it shows the scientific side of the camera.

Check out the work of The Center for Civil War Photography. They do amazing work identifying the exact spots where famous photos were taken. You can actually go to Gettysburg today, stand in the exact spot Timothy O'Sullivan stood, and see how the rocks haven't moved an inch in 160 years.

Seeing the past this clearly is a heavy experience. It stops being "history" and starts being "humanity." These weren't characters in a story. They were people who were cold, hungry, and probably scared out of their minds. The camera caught that. And thankfully, it hasn't let go.