You’ve seen it. That shaky, black-and-white ghost of a man stepping off a ladder into a sea of gray dust. It’s arguably the most famous video in human history. But honestly, when we talk about real footage of moon landing missions, most of us are actually looking at a copy of a copy of a broadcast that barely survived its own journey to Earth.

It was 1969. The technology was, by today's standards, basically ancient. We’re talking about a time when computers had less processing power than a modern toaster. Yet, they managed to beam a live signal from 238,000 miles away.

People often ask why it looks so "fake" or "low-res." The answer isn't a Hollywood basement. It's physics. Specifically, the physics of bandwidth and the limitations of the Westinghouse camera tucked into the Lunar Module's side panel.

Why the real footage of moon landing looks the way it does

Let's get into the weeds of the hardware. NASA couldn't just use a standard TV camera. Standard broadcast signals in the US back then (NTSC) used 525 lines of resolution at 30 frames per second. That required a huge amount of bandwidth—way more than the S-band antenna on the Lunar Module could handle while also juggling voice data and telemetry.

So, they compromised.

Engineers at Westinghouse Electric Corporation developed a "slow-scan" camera. It ran at just 10 frames per second with only 320 lines of resolution. It was a weird, custom format. Because the world’s TV networks couldn't broadcast that signal directly, NASA had to "convert" it on the fly.

How? They literally pointed a high-quality TV camera at a monitor displaying the slow-scan feed.

Think about that. You are watching a recording of a screen. That is why the real footage of moon landing events often feels blurry or high-contrast. Every time you convert a signal like that, you lose detail. You get "ghosting." You get those weird trails behind Buzz Aldrin’s arms. It wasn't a glitch in the matrix; it was just 1960s tech trying its best to stay alive in a vacuum.

The mystery of the missing tapes

There is a persistent rumor that NASA "lost" the original tapes. This is actually true, though not in the way conspiracy theorists love to claim.

🔗 Read more: Smart TV TCL 55: What Most People Get Wrong

In the early 2000s, NASA looked for the original magnetic telemetry tapes from the Apollo 11 EVA (Extravehicular Activity). These tapes held the raw, high-quality slow-scan data before it was converted for TV. They couldn't find them. After a massive search, they realized the tapes had likely been erased and reused during the 1970s and 80s when the agency was facing severe budget cuts and a data storage crisis.

It's a tragedy of bureaucracy.

We lost the highest-definition version of the most important moment in 20th-century exploration because someone needed to save a few bucks on magnetic tape. However, the lower-quality broadcast footage—recorded at tracking stations in Australia like Parkes and Honeysuckle Creek—survived. That is what we watch today.

High-definition 16mm: The footage you rarely see

While the live TV feed was grainy, the astronauts were also carrying much better gear. They had 16mm Maurer Data Acquisition Cameras (DAC) and, most famously, Hasselblad 500EL cameras.

These weren't broadcasting live. They were shooting on actual film.

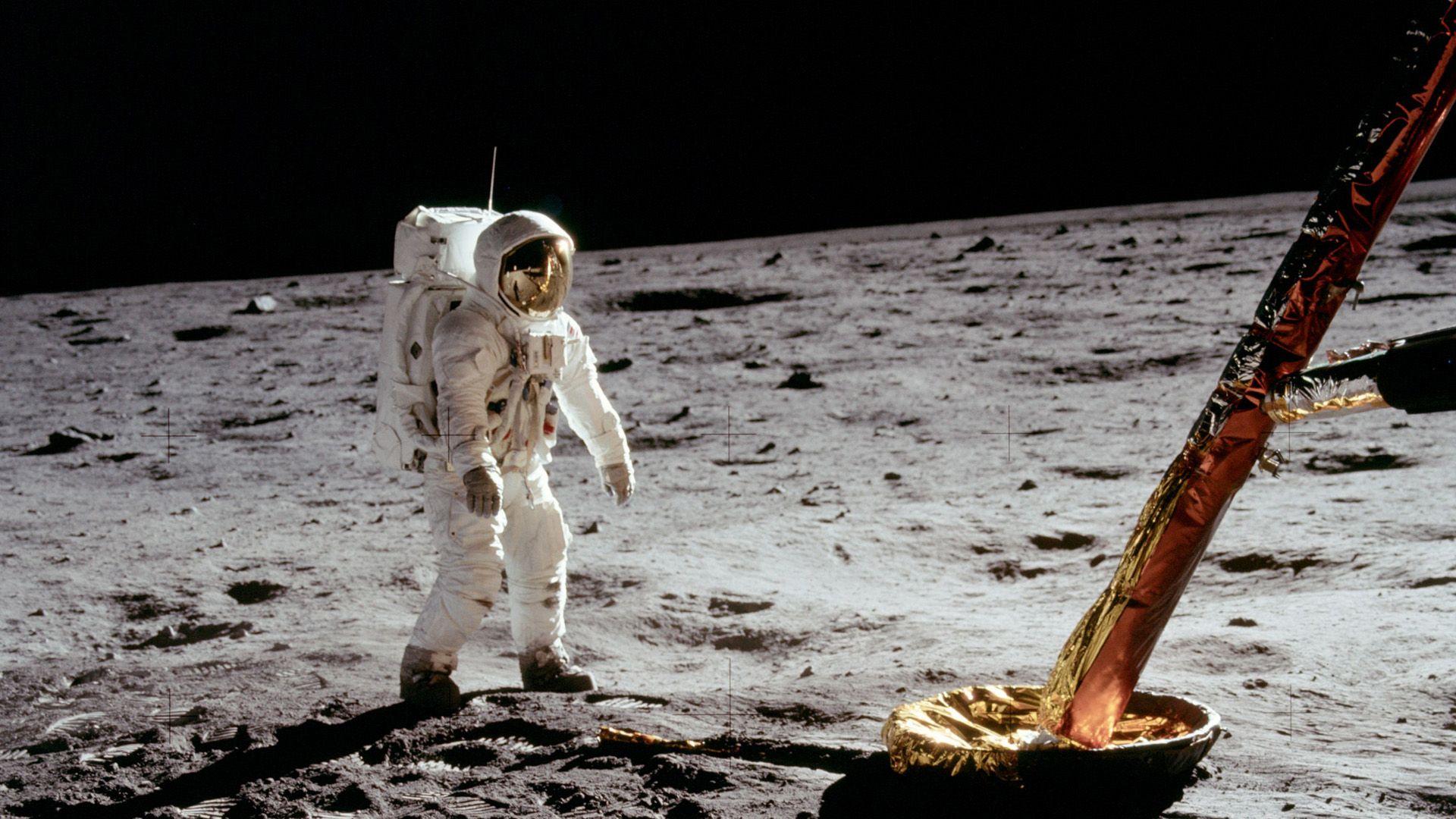

When you see crystal-clear, color real footage of moon landing operations, you’re usually looking at the 16mm film that was brought back to Earth and developed in a lab. This footage is stunning. You can see the gold foil of the Lunar Module shimmering. You can see the distinct, glass-like texture of the lunar regolith being kicked up by boots.

The 16mm film proves why the "it was filmed in a studio" argument falls apart. In a studio, dust behaves like it's in air. It billows. It forms clouds. In the vacuum of the moon, as seen in the DAC footage, every grain of dust follows a perfect parabolic arc. It falls instantly. There is no air to hold it up. Recreating that in 1969 would have required a vacuum chamber the size of a skyscraper, which... well, we didn't have those.

The Hasselblad factor

The still photos are even better. NASA chose Hasselblad because of their Zeiss lenses. The astronauts didn't have viewfinders; they had the cameras chest-mounted. They basically had to "point and pray."

💡 You might also like: Savannah Weather Radar: What Most People Get Wrong

The result? Thousands of some of the most compositionally perfect images ever taken. The detail in the 70mm film is equivalent to a modern digital sensor with nearly 100 megapixels. That’s why you can zoom in on the reflection in an astronaut’s visor and see the entire landing site mapped out in the curve of the glass.

Comparing Apollo 11 to later missions

The footage got better. By the time Apollo 15, 16, and 17 rolled around, NASA was using a much more advanced color camera. This one could be controlled remotely from Earth by a guy named Ed Fendell at Mission Control.

He’s the reason we have the famous shot of the Lunar Module ascending from the moon.

Think about the lag. There is a multi-second delay between Houston and the Moon. Fendell had to anticipate the liftoff and start the camera tilt-up several seconds before the engine actually fired. If he timed it wrong, he’d be filming empty space. He nailed it.

The color footage from the later J-series missions is vibrant. You can see the orange soil at Shorty Crater discovered by Harrison Schmitt. It looks like a different world because it is a different world, captured on superior equipment compared to the "experimental" feel of the 1969 reels.

Why does the flag "wave"?

This is the classic "gotcha" for skeptics. In the real footage of moon landing clips, the flag seems to move after the astronaut lets go.

"There's no wind on the moon!" they cry.

Correct. There is no wind. But there is inertia. The flag was held up by a horizontal crossbar because, without wind, a regular flag would just limp against the pole. The astronauts struggled to get the crossbar to extend fully. When they planted the pole, they had to twist it back and forth to get it into the hard ground.

📖 Related: Project Liberty Explained: Why Frank McCourt Wants to Buy TikTok and Fix the Internet

In a vacuum, there is no air resistance to stop a vibrating object. When they let go, the pole continued to oscillate. Without air to dampen the movement, it kept "waving" for far longer than it would on Earth. It wasn't wind; it was just physics being weirdly pure.

The restoration efforts of the 21st century

Technology has finally caught up to the moon. In 2009, for the 40th anniversary, NASA commissioned Lowry Digital (the company that restored Star Wars) to clean up the best surviving broadcast copies. They didn't "add" detail—that would be faking it. Instead, they used algorithms to strip away the grain and "noise" introduced by the 1969 conversion process.

The result is the cleanest version of the real footage of moon landing we will likely ever have.

More recently, independent creators have used AI-upscaling to bring the 16mm film up to 60 frames per second. While these are "enhanced" and not strictly raw historical records, they give us a visceral sense of what it felt like to stand there. The motion becomes fluid. The moon stops looking like a grainy dream and starts looking like a real, physical place you could walk on.

What we can learn from the reels today

Looking at this footage isn't just a nostalgia trip. It’s a masterclass in engineering under pressure. Every frame represents a solution to a problem that hadn't existed ten years prior. How do you lubricate a camera shutter so it doesn't freeze or weld shut in -250 degrees? How do you keep film from becoming brittle and snapping?

We have more "real" footage now than ever, thanks to the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter (LRO).

Launched in 2009, the LRO has photographed the Apollo landing sites from orbit. You can see the descent stages of the Lunar Modules still sitting there. You can see the tracks made by the Lunar Rover. You can even see the footpaths worn into the dust by the astronauts. These photos match the real footage of moon landing EVA maps perfectly.

Actionable steps for the curious observer

If you want to move beyond the three-minute clips on YouTube and really understand this footage, here is how to do it:

- Visit the Apollo Flight Journal: This is a NASA-run site that syncs the transcripts with the actual video and audio. It provides context for every "What's that?" moment in the footage.

- Watch the 16mm DAC footage specifically: Search for "Apollo 16mm Maurer film." It’s far superior to the TV broadcasts and shows the true physics of the lunar environment.

- Look at the raw scans: The "Project Apollo Archive" on Flickr has high-resolution scans of the original Hasselblad film magazines. They haven't been color-corrected or cropped for magazines. They are raw and breathtaking.

- Study the LROC images: Go to the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter Camera website and search for "Apollo landing sites." Seeing the 1969 footage side-by-side with 21st-century satellite imagery is the ultimate debunking tool.

The footage isn't perfect. It's flawed, grainy, and sometimes confusing. But those flaws are the thumbprints of a generation that built a bridge to the stars with slide rules and grit. The "realness" is in the imperfections.

To get the most out of your research, prioritize primary sources over documentary edits. Look for the uncut EVA tapes. When you see the astronauts spend ten minutes struggling with a single bolt or laughing because they tripped in the low gravity, the humanity of the event becomes undeniable. That’s the real value of these records—not just the "giant leap," but the hundreds of small, awkward, very human steps that took us there.