Writing a check feels like a relic from 1995. It’s clunky. It’s slow. Yet, in 2026, the Federal Reserve still tracks billions of check payments annually because, honestly, some industries just refuse to let go. If you’re looking at real checks front and back, you aren’t just looking at paper. You’re looking at a legal contract that is governed by the Uniform Commercial Code (UCC).

Most people mess this up. They sign the wrong place. They ignore the MICR line. Then they wonder why their mobile deposit got flagged for fraud.

The Anatomy of the Face: What’s Actually on the Front

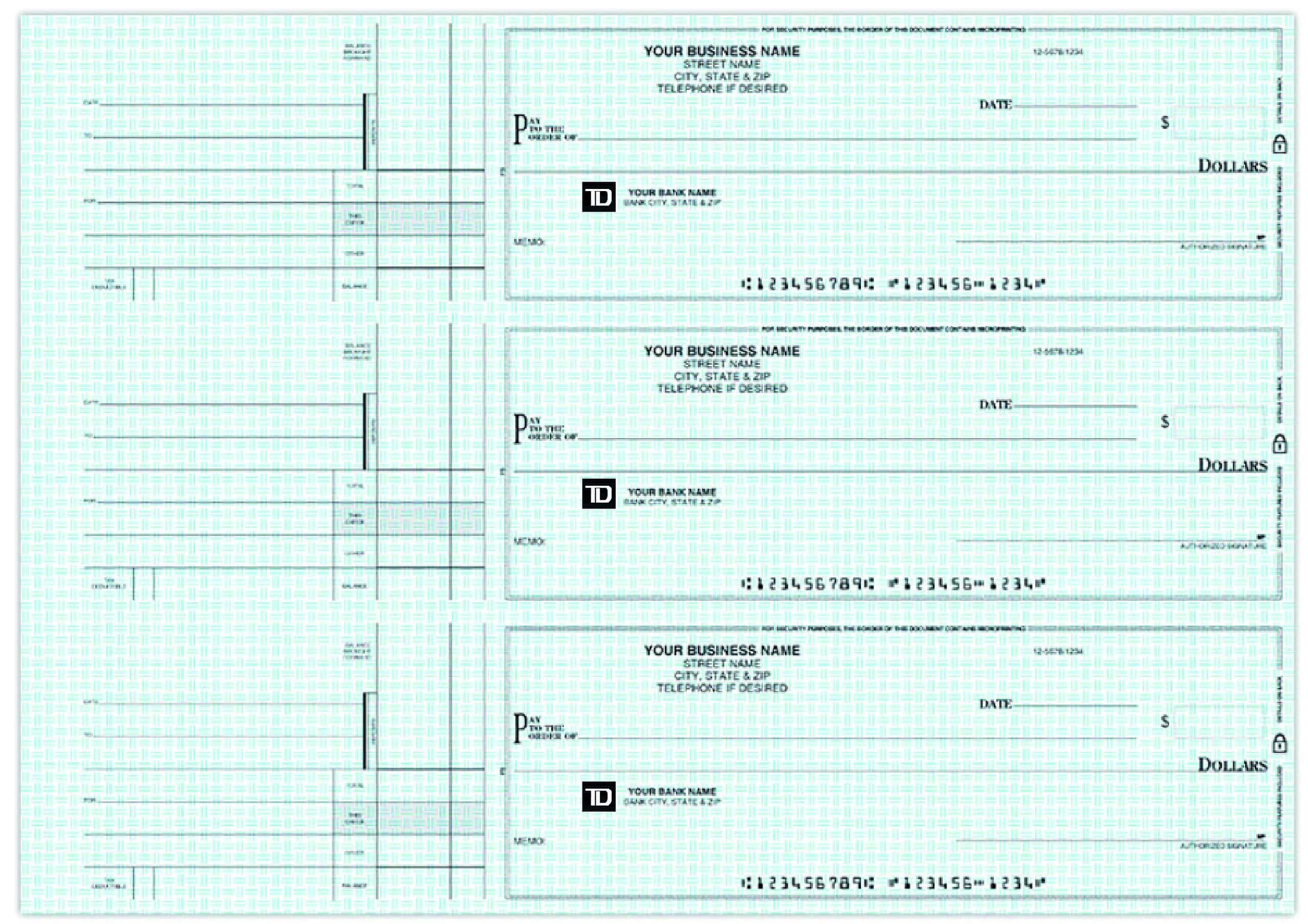

The front of a check is where the "order" happens. It’s a literal instruction to your bank to move money. If any piece is missing, the whole thing is basically a scrap of paper. You've got the personal info in the top left. That's obvious. But did you know that the check number in the top right isn't technically required by law? It’s there for your own bookkeeping, but a check without a number is still a legal instrument.

👉 See also: RM to IDR Rate: What Most People Get Wrong About Converting Ringgit

Then there’s the date. This is where things get weird.

In the United States, "stale-dated" checks are a real thing. Under UCC 4-404, a bank isn't legally obligated to pay a check that is more than six months old. They can pay it, but they don't have to. On the flip side, "post-dating" a check (putting a future date on it) doesn't actually stop a bank from cashing it early in many cases. It's a common myth that the date is a "lock." It isn't.

The Magic Ink: The MICR Line

Look at the very bottom. That weird, blocky font? That’s Magnetic Ink Character Recognition (MICR). It’s printed with special iron oxide ink.

The first set of numbers is the 9-digit routing transit number (RTN). This identifies the specific financial institution. Fun fact: the first two digits of the routing number indicate which of the 12 Federal Reserve districts the bank belongs to. If you see a "02," it's New York. A "12" means San Francisco.

The second set is the account number. The third set is the check number. If these numbers are blurry or printed with standard inkjet ink from a home printer, the high-speed sorting machines at the Fed will reject it. That’s why "real" checks feel different—they are printed on specific 24lb or 26lb security paper.

🔗 Read more: Unemployment File Claim NY: What Most People Get Wrong

Flipping It Over: The Back of the Check Secrets

The back is where the "endorsement" happens. This is the part that usually triggers the fraud department.

You’ll see a pre-printed line that says "Endorse Here." Stay inside the lines. Seriously. Regulation CC (Availability of Funds and Collection of Checks) dictates how banks handle these. If your signature drifts down into the area meant for bank stamps, it can interfere with the automated clearing process. This causes delays. It might even get the check sent back to you.

The Three Types of Endorsements

Most people just scrawl their name. That’s a Blank Endorsement. It's the most dangerous way to handle a check. Once you sign the back of a real check with a blank endorsement, it becomes "bearer paper." That means anyone who holds it can theoretically cash it. If you drop it in the parking lot after signing it, finders keepers (legally speaking, though it's still theft).

You should probably be using a Restrictive Endorsement.

Basically, you write "For Mobile Deposit Only at [Bank Name]" above your signature. Since the rise of mobile banking, the FDIC and various banking regulators have pushed for this because of "double-presentment" fraud. That’s when someone deposits a check via an app and then tries to cash the physical paper at a liquor store.

Then there’s the Special Endorsement. This is how you "sign over" a check to someone else. You write "Pay to the order of [Person's Name]" and then sign it. Warning: most big banks like Chase or Wells Fargo flat-out refuse to accept these anymore because the fraud risk is just too high.

Security Features You Can’t See on a Screen

If you hold a real check up to the light, you’ll see the watermark. It’s usually a logo or a pattern built into the paper fibers. It’s not printed on top; it’s in the paper.

Check out the "Amount" line. On high-security checks, that line isn't a line. It’s Microprinting. If you use a magnifying glass, you’ll see the line is actually the words "AUTHORIZED SIGNATURE" or "ORIGINAL DOCUMENT" repeated over and over. A photocopier can't replicate that. It just looks like a solid, blurry line on a fake check.

There is also the MP Icon. This stands for MicroPrint. If you see it, the check has security features that satisfy the American National Standards Institute (ANSI) requirements.

Chemically Sensitive Paper

Real checks are often treated with chemicals. If someone tries to use bleach or acetone to "wash" the ink off (a common scam where they change the payee name), the paper will literally change color. It might turn bright blue or show a "VOID" pattern. This is why you should never use a basic ballpoint pen if you can help it. Use a gel pen with pigmented ink (like a Uni-ball Signo). The ink gets trapped in the paper fibers, making it nearly impossible to wash without destroying the check itself.

Why the "Back" Matters for Mobile Deposits

When you take a photo of a check for your banking app, the software is looking for the shadows.

Modern banking AI checks the "front and back" for depth. It looks for the texture of the paper and the "bleed-through" of the ink. If you’re looking at a digital image of a check and the signature on the back doesn't show a slight ghosting on the front, it’s a red flag.

Also, look for the Original Document text on the back. It’s often printed in very light grey ink. This ink is designed to disappear or turn black when photocopied. It’s a simple "tell" for bank tellers.

Common Myths vs. Reality

- The "Memo" line is legally binding. Actually, no. You can write "Payment in Full" on a memo line for a debt, but cashing it doesn't always legally waive the rest of the debt depending on your state's laws. It’s mostly for your own records.

- You need a checkbook to write a check. Technically, you could write a check on a napkin if it had the routing number, account number, and a signature. However, your bank would likely refuse to process it because it can't go through their machines.

- If you have the "Front and Back," you have the money. No. Scammers love to send photos of the front and back of a check to prove they "sent payment." This is a classic scam. Until that physical paper or the electronic clearing file hits the Federal Reserve system, that check is just a digital ghost.

Actionable Steps for Handling Checks

- Audit your endorsement habits: Stop using blank endorsements. Always write "For Deposit Only" and your account number. It takes three seconds and prevents a lost check from becoming a total loss.

- Check the MICR line for "slickness": If you receive a check and the bottom numbers feel raised or shiny like a laser printer, be suspicious. Real MICR ink has a flat, dull appearance.

- Verify the "Padlock" icon: Look for a small padlock icon on the right side of the check. It should be accompanied by a list of security features printed on the back. If the icon is there but the description is missing, it's a counterfeit.

- Use the "Finger Rub" test: On many modern checks, there is heat-sensitive ink (thermochromic). If you rub the logo or a specific spot with your thumb, the color should fade and then reappear. If it stays static, it's a fake.

- Cross-reference the Routing Number: Use the official Federal Reserve E-Payments Routing Directory to make sure the bank name on the check matches the routing number at the bottom. Scammers often put a big bank name like "Bank of America" but use a routing number from a tiny credit union in a different state.