You’re standing at Berri-UQAM. It’s crowded. You’re staring at that spiderweb of primary colors on the wall, trying to figure out if you’re heading toward Honoré-Beaugrand or Angrignon. Most people think the metro map in Montreal is a simple grid. It isn’t. Not really. It’s a subterranean circulatory system that defies the actual geography of the city above it. If you try to map the tunnel distances to the street blocks in your head, you’re going to end up walking way more than you need to.

Montrealers have a love-hate relationship with the STM (Société de transport de Montréal). We complain when the Orange Line stalls because of a "door issue," but honestly, we’d be lost without it. The map itself is a masterpiece of 1960s design—specifically 1966—when the city decided to go all-in on rubber-tired trains. That choice changed everything. It meant the trains could handle steeper inclines, which is why the map looks the way it does, snaking under the Saint Lawrence River and climbing toward the mountain.

The Four Colors You Need to Know

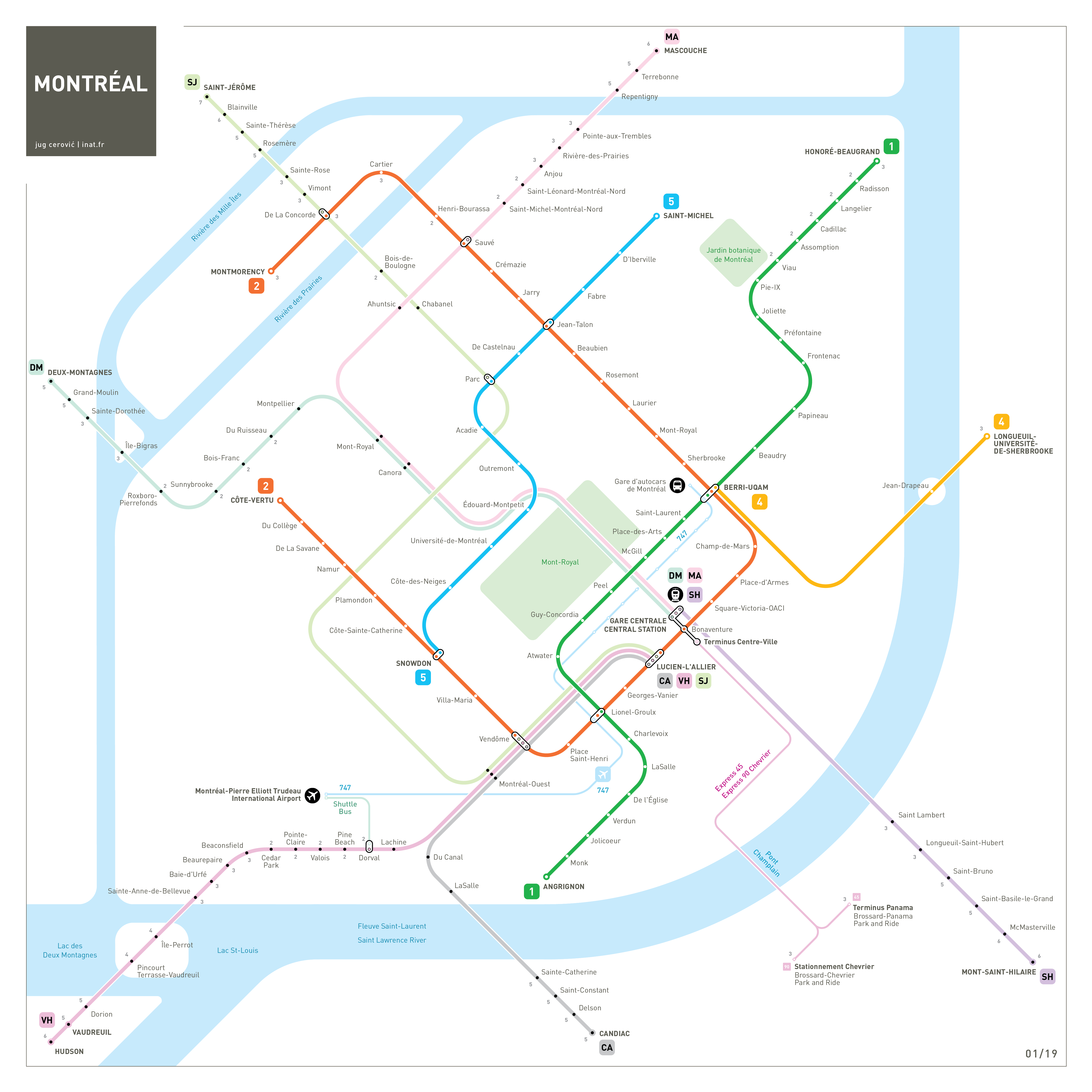

The system is stripped down to the basics: Green, Orange, Yellow, and Blue. There is no Red Line. People always ask why. Historically, a Red Line was planned to run along the CP Rail tracks, but it never happened. Now, we just have a gap in the rainbow.

The Green Line (Line 1) is your tourist lifeline. It hits the heavy hitters: Place-des-Arts, McGill, and the Olympic Stadium. If you want to see the vibe of the city change in real-time, get on at Atwater and ride it all the way to Frontenac. You’ll see the high-end shopping of Sainte-Catherine Street melt into the gritty, beautiful reality of the East End.

Then there's the Orange Line (Line 2). It’s a giant U-shape. It is also the bane of every commuter's existence during rush hour. It’s the busiest line in the system. It connects the residential dens of Rosemont and Plateau to the Financial District. If the Orange Line goes down, the city basically stops breathing.

The Yellow Line is a stub. Just three stations. It exists mostly to get people to Jean-Drapeau (the park/casino/Six Flags) and Longueuil. During the Formula 1 Grand Prix or Osheaga, this little line carries the weight of the world. Finally, the Blue Line (Line 5) stays up north. It’s the "student line," hitting the Université de Montréal and the diverse neighborhoods of Saint-Michel and Parc-Ex.

Why Geography on the Map is a Lie

Look closely at a metro map in Montreal and then look at a Google Map. They don't match. The metro map uses a "diagrammatic" approach. This means it prioritizes readability over distance accuracy.

For instance, the distance between Peel and McGill looks the same as the distance between Henri-Bourassa and Cartier. It’s not. Not even close. You can walk from Peel to McGill in five minutes. If you try to walk from Henri-Bourassa to Cartier, you’re crossing a literal bridge over a river into another city (Laval). Don't do that.

There’s also the "Montreal North" confusion. In Montreal, "North" is actually Northwest. The city is tilted. The metro map leans into this. When the map says a train is going "Nord," it’s following the city’s internal compass, not a magnetic one. This is why tourists often get turned around when they emerge from the tunnels. You think you're facing one way, but the sun is telling you something else.

The Secret of the Transfer Hubs

Berri-UQAM is the monster. It’s where the Green, Orange, and Yellow lines meet. It is a labyrinth. If you’re looking at the map and see that little circle connecting the lines, understand that it represents about five levels of stairs, escalators, and bus terminals.

Lionel-Groulx is the "smart" transfer. If you’re moving between the Green and Orange lines heading downtown, you literally just walk across the platform. It’s a beautiful piece of engineering. Jean-Talon is the other big one, connecting the Orange and Blue. It’s deep. Like, really deep. If you’re switching there, give yourself an extra five minutes just for the escalators.

The Missing Links: REM and the Future

If you look at a metro map in Montreal printed in 2026, you’ll notice something new: the REM (Réseau express métropolitain). It’s not technically the "metro," but it’s integrated. It’s an automated light rail system.

The REM adds a whole new layer to the map, connecting the South Shore, the Airport (finally!), and the West Island. It’s represented by a thinner, multi-pronged line. The transition hasn’t been perfectly smooth. There’s been plenty of talk about "shuttle buses" and "connection delays," but it’s the biggest expansion to the visual map since the 80s.

Public Art: The Map’s Hidden Layer

One thing the paper map won't tell you is that every single station is unique. In the 60s, the architects decided that no two stations should look alike. This was a radical idea.

- Champ-de-Mars: Has stunning stained glass by Marcelle Ferron.

- Namur: Features a giant floating geometric sculpture.

- Pie-IX: Is a brutalist concrete dream.

When you’re planning your route, you aren't just picking a destination; you're picking an aesthetic experience. If you have time to kill, getting off at a random stop on the Blue Line just to see the architecture is a valid Saturday afternoon plan.

Navigating the "Underground City" (RÉSO)

The metro map is also the skeleton for the RÉSO, or the Underground City. There are over 33 kilometers of tunnels. The map shows little "walking man" icons or shaded areas where the stations connect to shopping malls and office towers.

You can technically go from Place-des-Arts all the way to Lucien-L’Allier without ever putting on a winter coat. But be careful. The maps inside the tunnels are sometimes less clear than the actual metro map. You’ll see signs for "Place Montréal Trust" or "Complexe Desjardins." Just remember: follow the colored circles. If you find a metro entrance, you can find your way home.

Fares and the OPUS Card

You can't talk about the map without talking about how to actually ride the lines. We use the OPUS card. You can buy a single trip, but if you’re here for a bit, get a weekly pass.

💡 You might also like: Why Heritage of the Americas Museum Is One of San Diego’s Most Underrated Stops

A major trap for newcomers is the "Zones." The metro map in Montreal now spans Zone A (Montreal Island), Zone B (Laval and Longueuil), and Zone C (Outer suburbs). If you have a Zone A pass and you take the Orange Line to Montmorency (Laval), your card won't let you through the turnstile to get back. You’ll have to buy a specific "All Modes AB" ticket. It’s annoying. It’s a common mistake. Even locals screw it up.

Realities of the Commute

Let's be real for a second. The system is old. While the map looks pristine, the infrastructure is tired. You will see "Technical Overlays" mentioned on the screens. This is usually code for a broken train or someone dropped their phone on the tracks.

The STM is pretty good at updating their digital maps in real-time. If you see a line flashing red on the station monitors, check the STM website or their Twitter (X) feed immediately. They are surprisingly transparent about delays.

Also, the "Blue Line Extension" is a saga that has lasted decades. If you see a map showing the Blue Line going all the way to Anjou, check the date. It’s been "coming soon" since the Reagan administration. As of now, it’s still mostly a construction site and a dream.

Actionable Tips for Mastering the Map

- Download the "Chrono" or "Transit" app: The static map on the wall is great for orientation, but these apps give you the "real" map, including where the buses are.

- Look for the "Direction" names: We don't use "Eastbound" or "Westbound." We use the name of the final station on the line. On the Green Line, it's either Angrignon or Honoré-Beaugrand. On the Orange, it's Côte-Vertu or Montmorency.

- Avoid Berri-UQAM at 5:00 PM: If you can walk between stations downtown (like McGill to Place-des-Arts), do it. You'll save yourself the claustrophobia.

- The "Front or Back" Trick: If you're transferring at Lionel-Groulx or Berri, look at the signs on the platform. They tell you which end of the train is closer to the exit or the transfer stairs. It saves you a 200-meter walk underground.

- Check the Zone: Before you head to Longueuil or Laval, make sure your ticket covers "Zone B." A standard Montreal ticket will get you to Longueuil, but it won't get you back through the gate.

The metro map in Montreal is more than just a navigation tool; it's a cultural icon. It’s printed on t-shirts, mugs, and posters in every souvenir shop in the Plateau. It represents a city that decided to build down instead of just out. Once you stop trying to make it match the world above, and start trusting the colors, you’ll realize it’s actually one of the most intuitive systems in North America. Just watch out for the "Direction Montmorency" trap if you only have a Montreal ticket.

To get started, buy an OPUS card at any station vending machine—they take credit and debit—and load a 3-day pass if you're visiting. It’s the cheapest way to see the whole map without worrying about individual fares. Take the Green Line to Pie-IX to see the biodome, then hop over to the Orange Line for dinner in Little Italy (Jean-Talon station). It’s the best way to see the "real" Montreal.