Your feet are weird. Honestly, most people don’t think about them until a shoe rubs a blister or a sharp pain shoots through the heel during that first step out of bed. But there is a massive community of practitioners—and a growing body of biomechanical research—that views the underside of your foot as a literal biological blueprint. When we talk about a map of the foot, we aren't just looking at one thing. We’re looking at a collision between ancient reflexology traditions and modern podiatric science.

It’s fascinating.

If you look at a traditional reflexology chart, the foot is essentially a miniaturized mirror of the human body. The toes represent the head and neck. The ball of the foot corresponds to the chest and heart. The arch handles the digestive organs, and the heel is linked to the lower back and pelvic region. While some skeptics dismiss this as pseudoscience, millions of people swear by the tension release they feel when specific "zones" are manipulated. But let's get real for a second—even if you don't believe pressing your pinky toe will cure a headache, the map of the foot is objectively vital for understanding how you move, why your knees hurt, and how your nervous system processes sensory input.

The Reflexology Perspective: More Than Just a Massage

Reflexology operates on the principle that there are "reflex points" on the feet that connect to specific organs and systems via energetic pathways or nervous system signaling. It’s been around for thousands of years, with roots in ancient Egypt and China. In 1917, Dr. William Fitzgerald introduced "Zone Therapy" to the West, claiming that the body is divided into ten vertical zones that end in the fingers and toes.

When you look at a reflexology-based map of the foot, the layout is surprisingly logical. The right foot generally corresponds to the right side of the body, and the left foot to the left. The liver, being on the right side of your torso, is mapped onto the right arch. The stomach, tucked more to the left, is found on the left foot.

👉 See also: Why the Ginger and Lemon Shot Actually Works (And Why It Might Not)

Practitioners like those certified by the American Academy of Reflexology argue that "crystalline deposits" or tension in these foot maps can indicate issues elsewhere. They aren't diagnosing cancer by touching your heel, but they are looking for "congested" areas. Whether this is true energy work or just the fact that the foot has over 7,000 nerve endings is a point of constant debate. Regardless, the map provides a structured way to apply pressure that frequently results in a measurable reduction in cortisol levels and systemic stress.

Biomechanics and the Neural Map

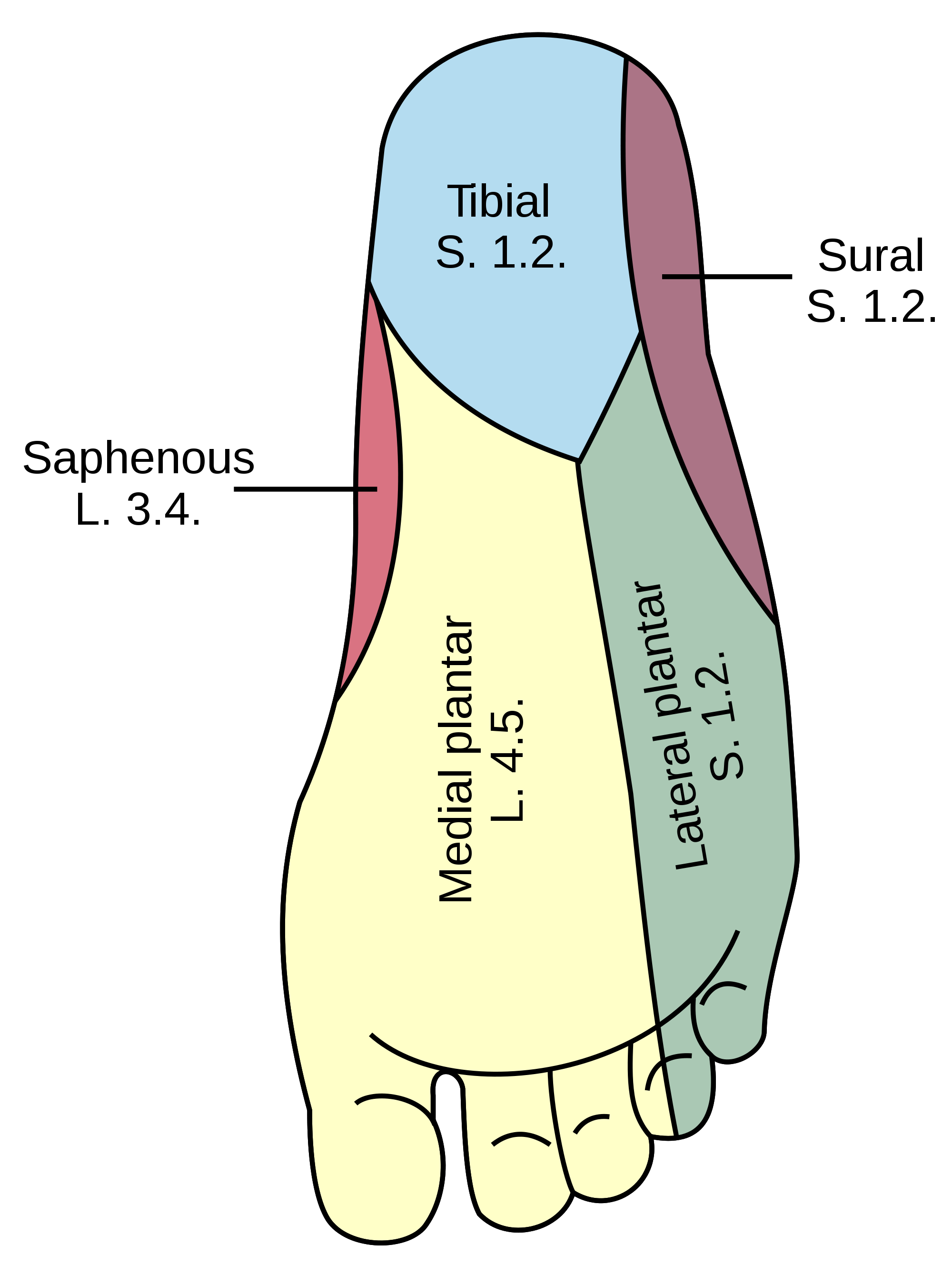

Switching gears to "hard" science, podiatrists and neurologists have their own version of a map of the foot. This isn't about organs; it's about mechanoreceptors.

Your brain has a "homunculus"—a sensory map of the body located in the somatosensory cortex. The feet take up a huge chunk of real estate here. Why? Because your brain needs constant, high-fidelity data about the ground to keep you from falling over.

- The Forefoot and Proprioception: The area under your toes and the "knuckles" of the foot are packed with sensors that tell you about the texture and incline of the surface.

- The Lateral Column: The outer edge of your foot is built for stability. If your "map" shows too much pressure here (supination), it often signals issues with ankle stability or tight peroneal muscles.

- The Medial Longitudinal Arch: This is the shock absorber. A collapse here (flat feet) sends a ripple effect up the "kinetic chain," often causing the internal rotation of the femur and subsequent hip pain.

Dr. Kevin Kirby, a renowned podiatrist and expert in foot biomechanics, often discusses how the "spatial location of force" on the foot map dictates the stress on our bones. If the map of your gait shows a heavy "strike" on the medial side of the hallux (big toe), you're at a high risk for bunions. This isn't mystical; it’s physics.

✨ Don't miss: How to Eat Chia Seeds Water: What Most People Get Wrong

What Your Calluses are Saying

Look at your feet right now. See those patches of thickened skin? Those are data points on your personal map of the foot.

Calluses are a protective response to friction and pressure. If you have a massive callus on the side of your big toe, you’re likely "rolling off" the inside of your foot, possibly due to a functional hallux limitus (a stiff big toe). A callus under the second toe joint often suggests that your second metatarsal is longer than your first—a common condition called Morton’s Toe—which shifts your entire balance map.

It's sorta like a wear pattern on a tire. If the tread is gone on one side, you don't just buy a new tire; you check the alignment. Your foot map is your alignment report.

The Emerging Science of Foot Sensitivity

Recent studies, including research published in the Journal of Rheumatology, have explored how the sensitivity of the foot map changes with age or disease. For instance, people with peripheral neuropathy (common in diabetes) lose sections of their foot map. It’s like a GPS losing its signal in a tunnel. When the brain can't "see" the map of the foot, it compensates by widening the gait or staring at the ground while walking.

🔗 Read more: Why the 45 degree angle bench is the missing link for your upper chest

But here is the cool part: you can "remap" your brain's connection to your feet.

Using "textured insoles" or simply walking barefoot on varied surfaces like grass, sand, or gravel forces the brain to pay attention to the sensory map of the foot. This neuroplasticity can actually improve balance in older adults. It’s basically like recalibrating a touch screen.

Reading the Map: A Practical Breakdown

If you want to use the map of the foot to actually improve your health, you have to look at it through both lenses—the holistic and the structural.

- The Big Toe (Head/Brain): In reflexology, this is the center for mental clarity. In biomechanics, this is the "lever" for your entire stride. If your big toe doesn't work, your brain loses its most important movement signal.

- The Arch (Digestion/Core): Reflexologists target the arch for IBS or indigestion. Physiotherapists look at the arch as the "core" of the foot. A weak arch often correlates with weak deep-core muscles in the abdomen.

- The Heel (Pelvis/Lower Back): Heel pain is frequently labeled as plantar fasciitis, but on the foot map, it's the anchor. Tension here is almost always linked to tight calves and a tight posterior chain (hamstrings and glutes).

Sometimes, a pain in the "lung zone" of the foot (the ball of the foot) is actually a Morton’s Neuroma—a pinched nerve. Other times, it’s just stress. The key is not to get hyper-fixated on one interpretation.

Actionable Steps for Foot Health

Stop treating your feet like "bricks" at the end of your legs. They are complex sensory organs.

- Self-Mapping: Once a week, sit down and press firmly into every part of your sole. Note where it’s tender. Is it the "kidney" reflex point, or is it just the spot where your shoe's arch support is too high?

- The Golf Ball Trick: Roll a golf ball under the arch of your foot for two minutes a day. This breaks up fascial adhesions and "wakes up" the neural map, sending a surge of sensory data to your brain.

- Vary Your Terrain: If you only walk on flat, carpeted floors or paved sidewalks, your foot map becomes "blurry." Walk on grass. Walk on a rug with a deep pile. Give your sensors something to do.

- Check Your Wear Patterns: Look at the bottom of your oldest pair of sneakers. If the outside heel is worn down but the rest looks new, your "map" is heavily skewed toward the lateral side. You might need to work on ankle mobility.

Understanding the map of the foot is about realizing that your feet are the foundation of your entire physical experience. Whether you’re rubbing a specific point to calm your nervous system or strengthening your arch to save your knees, paying attention to the soles of your feet is one of the highest-leverage things you can do for your long-term mobility. Take the shoes off. Look at the map. Start paying attention to what the ground is telling you.