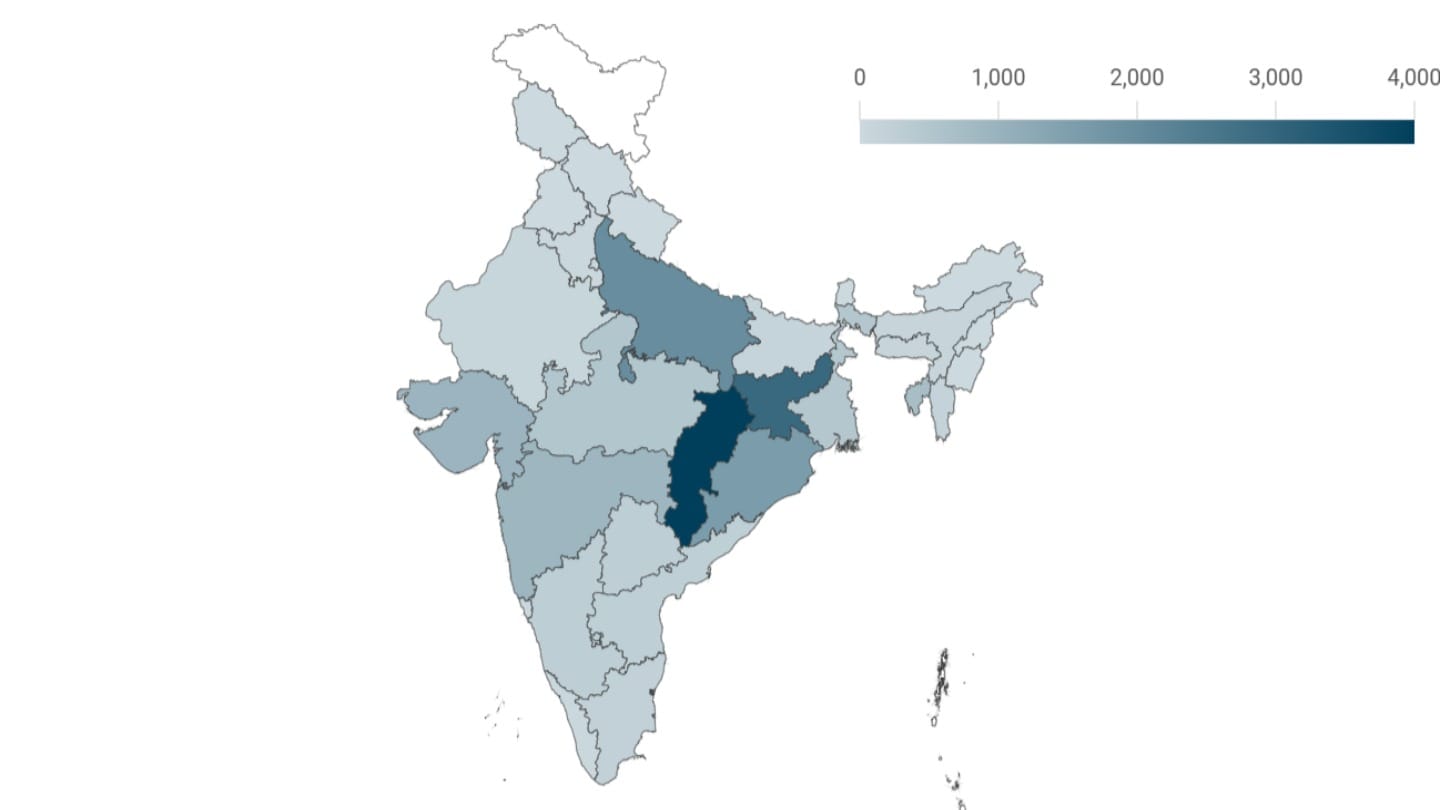

India is currently in a weird, hopeful, but occasionally terrifying spot with malaria. If you look at a malaria map of India today versus what it looked like even five years ago, the progress is honestly staggering. We are talking about a massive drop in cases. The World Health Organization (WHO) and the National Center for Vector Borne Diseases Control (NCVBDC) have been tracking this shift closely. But here’s the thing: malaria hasn't vanished. It’s just moved. It’s huddling in specific corners of the country, and if you’re traveling or living in those zones, the "national decline" doesn't mean much to your immune system.

The map is no longer a monolith. It’s a patchwork. You’ve got states like Kerala and Tamil Nadu that are basically knocking on the door of malaria-free status. Then you look at the tribal belts of Odisha, Chhattisgarh, and Madhya Pradesh, where the geography of the disease is a whole different beast. It’s a story of two Indias. One is winning the war through urban infrastructure and rapid testing; the other is still fighting a rugged, uphill battle against dense forests, heavy monsoons, and a species of mosquito that refuses to play by the rules.

The Hotspots: Where the Malaria Map of India Glows Brightest

It isn't a secret that the "Heart of India" bears the heaviest burden. When experts analyze the malaria map of India, they focus heavily on the High Burden High Impact (HBHI) states. We’re talking about Odisha, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, and Madhya Pradesh. These four states have historically accounted for a massive chunk of the total cases in the country. Why? It isn’t just about "poor sanitation." That’s a lazy explanation.

It’s the forest.

The Anopheles fluviatilis mosquito loves the shade and the slow-moving streams of the central Indian highlands. This mosquito is incredibly efficient at spreading Plasmodium falciparum, the deadlier of the two main malaria parasites in India. In places like Malkangiri in Odisha or Bastar in Chhattisgarh, the malaria map isn't just a data visualization—it's a reflection of the terrain. The high forest cover makes it hard for health workers to reach villages, and the humidity keeps the mosquitoes breeding year-round.

Contrast that with the North East. For decades, states like Tripura and Mizoram were deep red on the map. They’ve made incredible strides recently. Tripura, specifically, saw a massive collapse in case numbers thanks to "DAMaN" (Durgama Anchalare Malaria Nirakaran), an initiative that basically took the fight into the most remote, inaccessible corners. They didn't wait for patients to come to the clinic; they took the tests and the bed nets into the jungle. It worked.

👉 See also: How Much Sugar Are in Apples: What Most People Get Wrong

The Urban Paradox and the Rise of Vivax

You might think big cities are safe. Mostly, they are. But cities like Mumbai and Chennai have their own version of the malaria map of India. In urban centers, the culprit is usually Anopheles stephensi. This mosquito is a city dweller. It breeds in overhead tanks, construction sites, and even those tiny puddles of water in the trays under your air conditioner.

Urban malaria is often dominated by Plasmodium vivax. While falciparum is the one that usually kills you through cerebral malaria or organ failure, vivax is the "relapsing" kind. It hides in your liver. It waits. You think you’re cured, and then three months later, the shivers come back. This makes mapping urban malaria tricky because the person might have caught it in one neighborhood but only shows symptoms weeks later in another.

Climate Change is Redrawing the Lines

Here is something people aren't talking about enough: the map is shifting North. Historically, the Himalayan belt and high-altitude regions were too cold for mosquitoes to survive. Biology has a temperature threshold. But as the climate warms, the "transmission window" is opening up in places like Himachal Pradesh and higher altitudes of Uttarakhand.

We are seeing mosquitoes move into valleys where they didn't exist twenty years ago. The malaria map of India is literally expanding upwards. If the monsoon becomes more erratic—heavy bursts of rain followed by long dry spells—it creates the perfect "stagnant pool" environment for breeding. The old maps we used in the 90s are essentially junk now.

Understanding the Parasite Split

To really read the map, you have to know what you're looking at. India is one of the few places where we have a nearly 50-50 split between two types of malaria:

✨ Don't miss: No Alcohol 6 Weeks: The Brutally Honest Truth About What Actually Changes

- Plasmodium Falciparum: The "heavy hitter." Mostly found in the forest belts and the North East. It’s the one that shows up as the "danger zone" on most health maps.

- Plasmodium Vivax: The "persistent" one. More common in the plains and urban areas. It's harder to eliminate because of that liver-stage dormancy.

What Most People Get Wrong About Prevention

A lot of folks look at a malaria map of India, see their state is "light yellow" or "green," and stop using repellent. That's a mistake. The map represents reported cases. It doesn't represent the absence of mosquitoes.

Also, there's a growing issue with insecticide resistance. In some parts of India, the standard synthetic pyrethroids we use in bed nets and sprays aren't working like they used to. The mosquitoes are evolving. This means even if you're in a "low-risk" zone on the map, the local mosquitoes might be harder to kill if they happen to be carrying the parasite.

Real-World Nuance: The Odisha Success Story

If you want to understand how to fix the map, look at Odisha. They were the "malaria capital" for a long time. Then they launched a massive, ground-level offensive. They distributed millions of Long-Lasting Insecticidal Nets (LLINs). They trained "ASHA" workers (community health volunteers) to use Rapid Diagnostic Tests (RDTs).

Before RDTs, you had to send a blood slide to a lab and wait days. By then, the patient was either better or dead. Now? A finger prick and 15 minutes later, you know if it's malaria. This speed is what turned the Odisha map from dark red to a manageable orange. It’s proof that the map isn't destiny; it’s a policy outcome.

Actionable Steps for Navigating the Map

If you are living in or traveling through India, don't just glance at a national-level map. You need to be more granular.

🔗 Read more: The Human Heart: Why We Get So Much Wrong About How It Works

1. Check the District-Level API

API stands for Annual Parasite Incidence. If the API of a district is above 1, it’s considered a high-risk area. Before traveling to places like Bastar, Gadchiroli, or the rural interiors of the North East, check the local API. Anything above 2 is a "take-your-pills" kind of zone.

2. Time Your Risks

The malaria map of India is seasonal. It "lights up" during and immediately after the monsoon (July to November). If you are in a high-risk state during these months, your precautions need to triple.

3. Recognize the Symptoms Early

Malaria in 2026 doesn't always look like the "classic" version with bone-shaking chills. Sometimes it’s just a persistent low-grade fever, a headache, or weirdly enough, digestive issues. If you’ve been in a shaded, forested, or high-API area, get a test. It’s cheap, and it’s everywhere.

4. The "Dawn and Dusk" Rule

Regardless of what the map says, the Anopheles mosquito is a night owl. Well, a twilight owl. They are most active between dusk and dawn. If you're in a high-burden state like Jharkhand, this is the time to be under a net or covered in DEET.

5. Demand the Right Test

In urban areas, doctors sometimes just test for vivax. If you've been traveling, insist on a bivalent RDT that checks for both falciparum and vivax. Knowing which one you have changes the treatment entirely, especially since vivax requires a 14-day course of Primaquine to clear the liver, whereas falciparum requires ACT (Artemisinin-based combination therapy).

India is aiming for a "Malaria Free" status by 2030. It’s an audacious goal. To get there, the malaria map of India needs to see the "red" disappear from the tribal heartlands. It's not just a medical challenge; it's a logistical one. But for the average person, the map is a reminder that while the country is winning the broad war, the local skirmishes are still very much active. Stay vigilant in the green zones, and stay protected in the red ones.