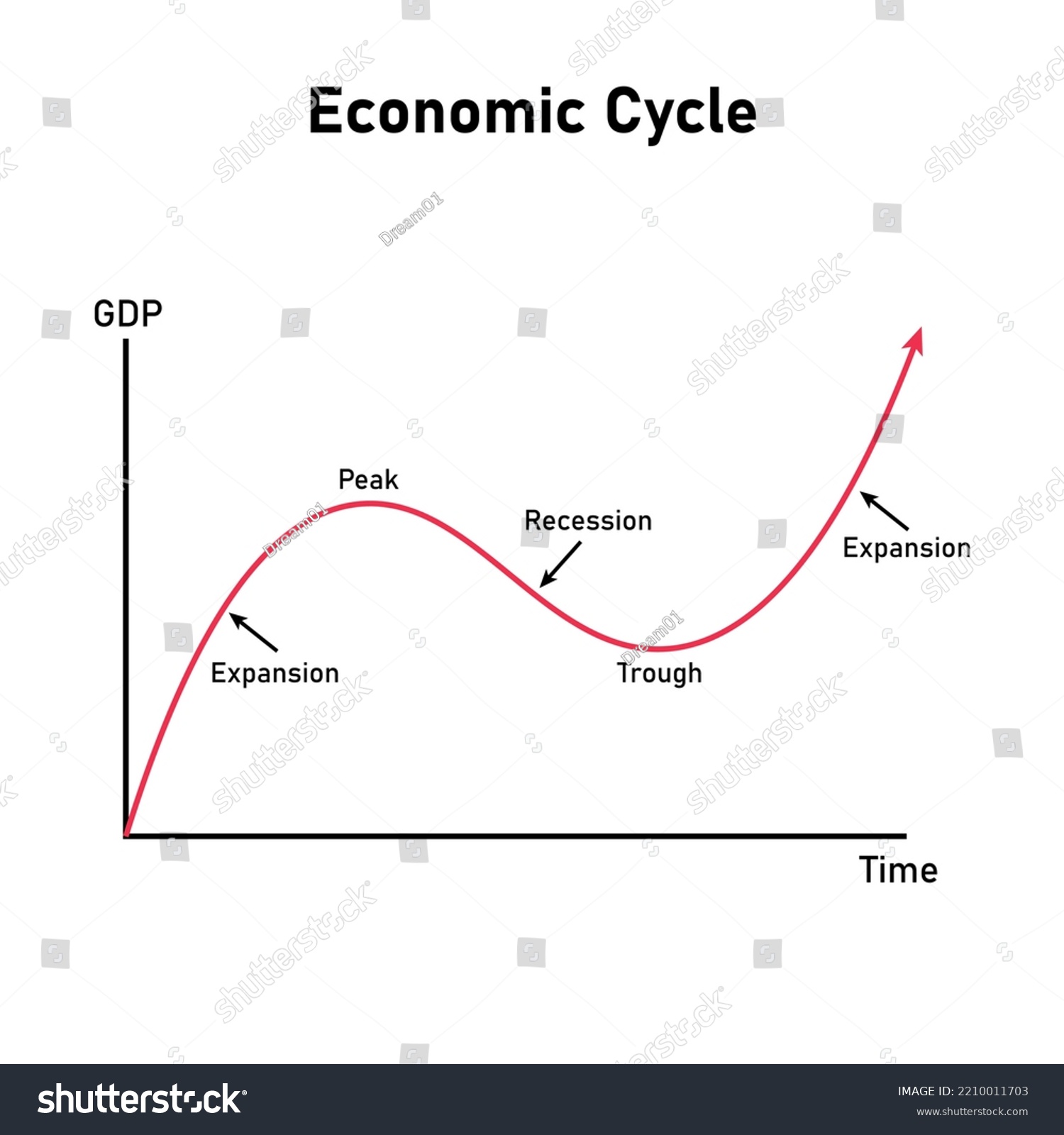

You've probably seen that smooth, wavy line in every macroeconomics textbook since high school. It looks like a gentle roller coaster. Up goes the expansion, there's a peak, down comes the recession, and then we hit the trough. Easy, right? Honestly, if the real economy actually looked like that clean graph for business cycle, we’d all be millionaires. We’d know exactly when to sell our tech stocks and when to buy that fixer-upper in the suburbs.

But real life is messier.

The "cycle" isn't a circle. It’s more like a jagged staircase being hit by a sledgehammer every few years. When you look at a graph for business cycle—specifically the ones provided by the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER) or the Federal Reserve—you aren't looking at a law of physics. You're looking at human psychology, inventory mistakes, and sometimes, just plain bad luck.

📖 Related: Who Benefits the Most From DEI Programs: The Answer Might Surprise You

The Four Phases Aren't Equal (And That’s the Trap)

Most people think the expansion and the recession are two sides of the same coin. They aren't. In the United States, since World War II, expansions have lasted an average of about 65 months. Recessions? They usually wrap up in about 11.

If you're staring at a graph for business cycle and expecting the "down" part to last as long as the "up" part, you're going to miss the boat. Markets move fast.

The Peak is a Ghost

The peak is the highest point on the graph. It’s the moment of maximum output. But here’s the kicker: nobody knows they’re at the peak when they’re actually standing on it. It feels great. Consumer confidence is through the roof. Unemployment is low. You’re probably thinking about a promotion.

Then, something breaks.

Maybe it’s the inverted yield curve—a classic signal where short-term debt pays more than long-term debt. This has preceded almost every U.S. recession for the last fifty years. When that line on the graph starts to bend downward, it’s rarely a cliff. It’s a slide.

Recession vs. Depression

People toss these words around like they’re interchangeable. They aren't. A recession is generally defined as two consecutive quarters of declining GDP, though the NBER uses a more holistic "significant decline in economic activity spread across the economy." A depression? That's just a recession that forgot to leave. Think 1929. Think a 10% drop in GDP.

Why the Graph for Business Cycle Looks Different Now

If you look at a graph for business cycle from the 1800s, it looks like a heart monitor for someone having a panic attack. Huge spikes. Deep, dark valleys.

Why? Because back then, we were mostly an agrarian and manufacturing economy. One bad harvest or one railroad bubble popping could tank the entire system. Today, we have "automatic stabilizers." Things like unemployment insurance and a diverse service sector act as a shock absorber.

But don't get too comfortable.

The COVID Anomaly

Take a look at the 2020 data point. It’s the weirdest blip in economic history. We saw the sharpest, fastest drop ever recorded, followed by a recovery that looked like a "V" on steroids. It defied the traditional logic of the graph for business cycle because it wasn't caused by internal economic rot. It was an external "exogenous shock."

Usually, a recession happens because the economy gets "overheated." Businesses over-expand. Consumers take on too much debt. The graph turns down because the system needs to purge the excess. In 2020, we just turned the lights off.

Real Indicators You Should Actually Follow

Stop looking at the stock market as a proxy for the business cycle. The market is forward-looking; it’s a bet on what people think will happen in six months. If you want to understand where we are on the graph for business cycle, you need to look at the "boring" stuff.

- The Yield Curve: Keep an eye on the spread between the 10-year and 2-year Treasury notes. When it goes negative, the clock is ticking.

- Inventory-to-Sales Ratio: If warehouses are full but cash registers are quiet, a contraction is coming.

- Real Personal Income: If people have less money in their pockets after inflation, they stop buying. The cycle turns.

Economist Nouriel Roubini—often called "Dr. Doom" for predicting the 2008 crash—frequently points out that these cycles are becoming more erratic due to "mega-threats" like climate change and geopolitical shifts. The old, smooth curves are becoming relics of a simpler time.

📖 Related: How to obtain W2 from past employer without losing your mind

Misconceptions That Kill Small Businesses

I've talked to dozens of founders who made the same mistake: they assumed the "Expansion" phase of the graph for business cycle would last forever. They signed 10-year leases at the peak of the market.

You have to remember that "mean reversion" is a real thing. If growth is significantly above the long-term trend of about 2% to 3% for too long, a correction isn't just possible; it's inevitable.

Also, "Soft Landings" are rare. The Federal Reserve often tries to slow down the economy just enough to stop inflation without causing a recession. It's like trying to land a 747 on a postage stamp during a hurricane. Sometimes they nail it, like in 1994. More often, they overcorrect, and the graph dips lower than intended.

How to Use This Data Today

Don't just stare at the line. Understand the components. The graph for business cycle is essentially a summary of four things:

- Consumption (What you buy)

- Investment (What businesses spend)

- Government Spending

- Net Exports

When you see the line moving, ask which of those four is driving the bus. Right now, in many developed economies, consumption is carrying the weight. If that falters, the graph shifts.

Actionable Next Steps for Navigation

To actually apply the theory of the graph for business cycle to your professional or personal life, you need to move beyond passive observation. Start by auditing your exposure. If the graph is currently in a late-stage expansion—characterized by high interest rates and tight labor markets—it is time to build "dry powder." This means increasing liquidity and reducing high-interest debt.

Next, diversify your "cyclical" vs. "defensive" holdings. Cyclical industries like luxury retail and construction flourish at the bottom of the trough and through the expansion. Defensive industries like healthcare and utilities stay relatively flat regardless of where the curve dips.

Finally, track the "Leading Economic Index" (LEI). This isn't just one number; it's a composite of ten different variables, including manufacturing hours and building permits. When the LEI trends down for several months, the graph for business cycle is almost certain to follow, regardless of what the "everything is fine" headlines say. Balance your optimism with the cold, hard reality of the data.

Understand the curve, but don't trust its symmetry. The economy doesn't owe you a smooth ride.