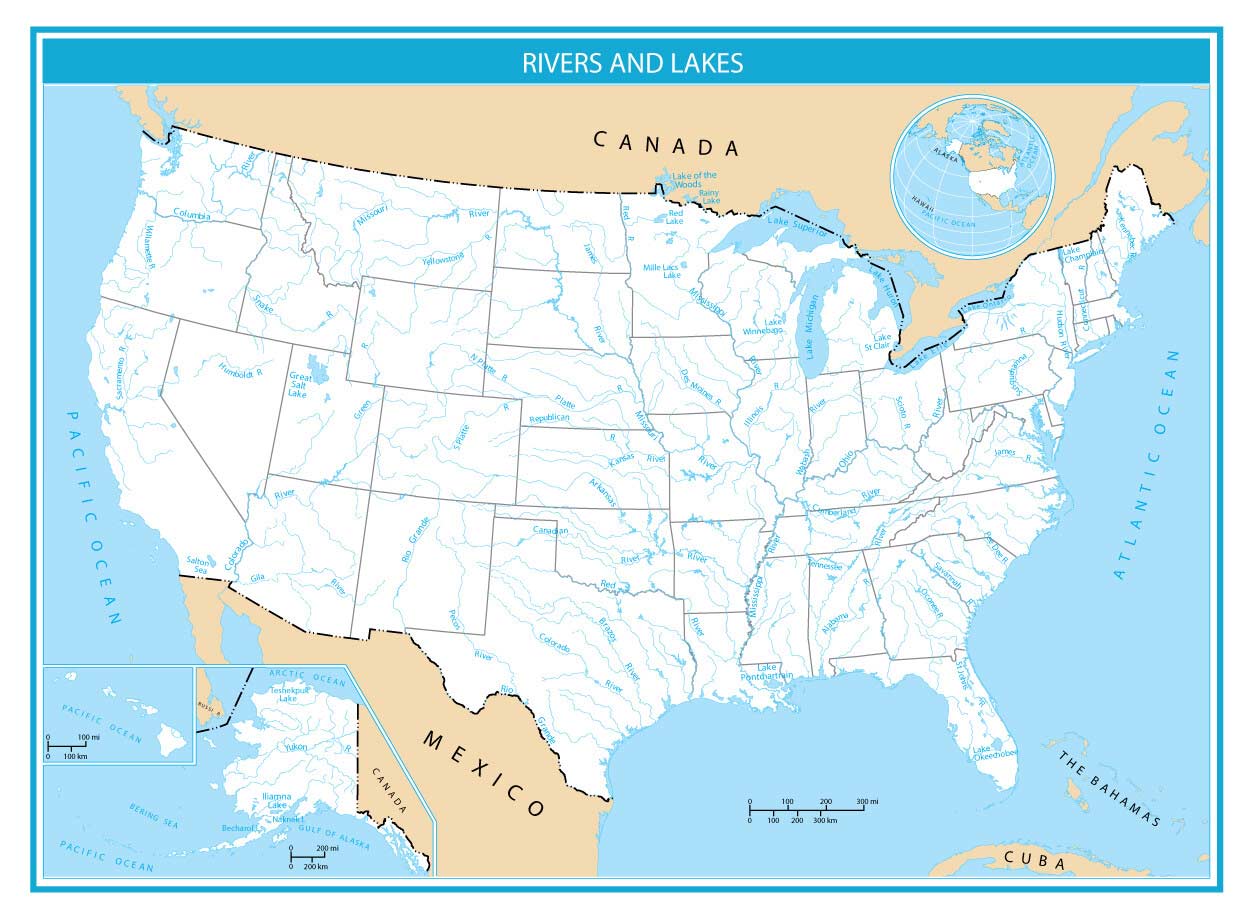

Ever looked at a map and realized it's mostly blue veins? It's wild. Most of us just see a river map of United States as a bunch of squiggly lines crossing state borders, but honestly, those lines are the only reason our cities even exist where they do. If you zoom in on a high-resolution hydrological map, the country starts to look less like a collection of 50 states and more like a massive, interconnected plumbing system. It’s chaotic. It’s beautiful. And it’s probably way more complicated than you think.

Take the Mississippi. Everyone knows it’s big. But did you know it’s basically the drain for about 40% of the continental U.S.? If you drop a leaf in western Pennsylvania, it could theoretically float all the way down to the Gulf of Mexico. That’s the kind of scale we’re talking about.

Why Your River Map of United States Looks Different Than Mine

The thing about mapping water is that it’s a moving target. Literally. Depending on which map you’re looking at, you might see "perennial" streams—those are the ones that flow all year—or you might see a "Strahler Stream Order" map that looks like a neon nervous system.

Geographers use these orders to rank how many tributaries feed into a main stem. A tiny creek is a "first-order" stream. When two of those meet, they make a second-order stream. By the time you get to the Mississippi, you’re looking at a 10th-order beast. Most people looking for a river map of United States just want to see where the big water is for a road trip or a fishing spot, but the real magic is in those tiny, unnamed veins that feed the giants.

If you look at the Great Basin on a topographical map, you’ll notice something weird. There’s a giant hole. In places like Nevada and parts of Utah, the rivers don't actually go to the ocean. They just... stop. They flow into salt lakes or evaporate in the desert. It’s called an endorheic basin. Basically, it’s a topographical "dead end" that defies the logic of the rest of the country’s drainage.

The Continental Divide Confusion

You’ve probably heard of the Continental Divide. It’s that invisible line running along the spine of the Rockies. It’s basically the ultimate "either/or" for every drop of rain.

Fall on the west side? You're going to the Pacific.

Fall on the east? You’re likely heading for the Atlantic or the Gulf.

But there’s actually more than one divide. The Eastern Continental Divide runs along the Appalachians, and the St. Lawrence River Divide sends water north toward the Great Lakes. A truly accurate river map of United States will show these invisible ridges that dictate the destiny of every gallon of water in the country. It’s kinda like a massive game of Plinko played on a continental scale.

The Big Players You Need to Know

When people talk about American rivers, they usually stick to the "Big Three": the Mississippi, the Missouri, and the Colorado. But that's oversimplifying things to a point where you miss the cool stuff.

- The Missouri River: Here’s a fun fact to annoy your friends with—the Missouri is actually longer than the Mississippi. It stretches about 2,341 miles compared to the Mississippi’s 2,320. Because it flows into the Mississippi, it gets relegated to "tributary" status, which feels a bit like being the older brother who still has to sit at the kids' table.

- The Rio Grande: It’s famous for being a border, but it’s also one of the most endangered rivers in the country. In some years, it doesn't even reach the sea anymore because of irrigation and droughts.

- The Columbia: This is the powerhouse of the Pacific Northwest. It’s got a volume of flow that makes other western rivers look like leaky faucets. It’s the reason that region has so much hydroelectric power.

- The Ohio River: It’s the industrial backbone. If the Mississippi is the heart, the Ohio is the heavy-lifting arm. It carries more volume than the Missouri because the eastern U.S. gets way more rain.

The "Ghost" Rivers of the West

If you look at a river map of United States specifically in the Southwest, you’re looking at a map of ghosts. Rivers like the Gila or the Salt are often dry for most of the year. They only wake up when a monsoon hits or the snow melts in the high country.

Cartographers have a hard time with this. Do you draw a blue line for a river that’s bone-dry in July? Usually, they use dashed lines to indicate "intermittent" flow. It’s a reminder that water in the West isn't a guarantee; it’s a seasonal guest.

👉 See also: Is Hampton Inn Manhattan Times Square North the Best Value Midtown Stay?

How Humans Broke the Map

We haven't exactly left these rivers alone. If you compared a river map of United States from 1800 to one from today, the lines might look the same, but the behavior is totally different. We’ve dammed, diverted, and straightened them so much that they’re basically liquid machines now.

The Army Corps of Engineers has been "fixing" rivers for over a century. They like things straight. Rivers, however, like to meander. A natural river wants to snake back and forth across a valley, creating "oxbow lakes" as it cuts off its own loops. By forcing them into straight channels to help barge traffic, we’ve sped up the water, which often makes downstream flooding way worse. It’s a classic case of solving one problem and accidentally creating three new ones.

The Mississippi’s Great Escape Attempt

The Mississippi River actually wants to leave New Orleans. Seriously. There’s a spot called the Old River Control Structure where the river is trying its hardest to jump its banks and flow down the Atchafalaya River instead.

If it did that, the ports of New Orleans and Baton Rouge would basically become stagnant lagoons. The economy would tank. So, we spend billions of dollars every few decades just to keep the river in its current bed. We’re basically holding a liquid giant in a chokehold.

Finding the Best Maps for Your Needs

If you’re actually looking to explore, don't just use Google Maps. It’s great for driving to Starbucks, but it’s terrible for water.

- USGS National Map: This is the gold standard. The U.S. Geological Survey has a "Hydrography" layer that shows every tiny trickle. It’s what professionals use.

- The "All Rivers" Map by Robert Szucs: This is a piece of art. He’s a digital cartographer who created a map where every river basin is color-coded. It makes the river map of United States look like a neon painting. It’s the best way to visualize how watersheds actually work.

- River Runner: This is a cool web tool where you can click anywhere in the U.S. and it will simulate the path a drop of water would take from that point to the ocean. It’s incredibly addictive and shows the connectivity of the system in a way a static map never could.

Real-World Action Steps for Water Enthusiasts

Don't just stare at the screen. If you want to actually understand the American river system, you've got to see it.

Start by identifying your own watershed. Where does your tap water come from? Where does the rain in your gutter go? You can find this out easily by checking the EPA’s "How’s My Waterway" tool. It’s a reality check to see how your backyard connects to the rest of the country.

If you’re planning a trip, look for "National Wild and Scenic Rivers." These are sections of rivers that are protected by the 1968 Act. They aren’t dammed, they aren't polluted, and they look exactly like they did 500 years ago. The Rogue in Oregon or the Chattooga in Georgia are prime examples.

Lastly, pay attention to the flow rates. Before you head out to a river, check the USGS "WaterWatch" site. It shows real-time gauges for thousands of spots. If a river is "in flood," stay away. If it’s "below base flow," you might be dragging your kayak over rocks all day. Mapping is one thing, but the actual state of the water changes by the hour. Stay safe, stay informed, and remember that those blue lines are the lifeblood of the whole continent.