Ever stared at a handful of resistors and felt like you were trying to decode a secret message from an alien civilization? It's okay. We've all been there. You're looking for a 10k ohm resistor for your breadboard project, but the stripes just aren't making sense. Specifically, when you stumble upon a 5 band resistor colour code, things get a little more crowded than the old-school four-band versions we learned about in school.

Here's the deal: that fifth stripe isn't just there for decoration. It represents precision. While the common four-band resistors are basically the "good enough" components of the electronics world, five-band resistors are for when you actually care about the math. If you're building a precision audio amplifier or a sensitive sensor circuit, that extra digit matters.

Why do we even have five bands anyway?

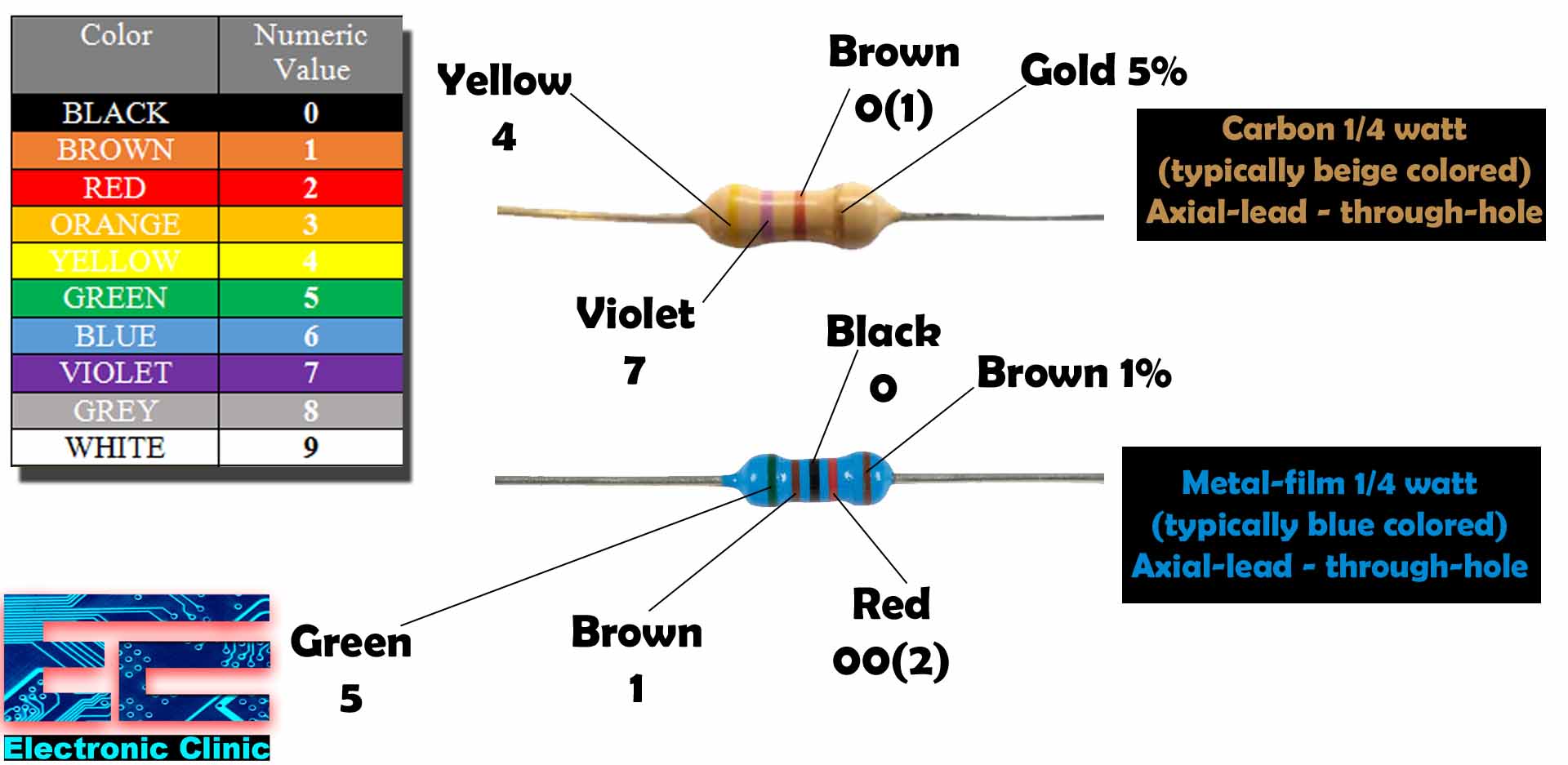

Most beginners start with four bands. In that setup, you get two digits, a multiplier, and a tolerance. It’s simple. But "simple" usually means a tolerance of 5% or 10%. In modern electronics, especially with the rise of high-speed digital circuits and precision analog gear, 5% error is a massive gap.

A 5 band resistor colour code provides a third significant digit. This allows for much more specific resistance values. Think of it like the difference between saying "the temperature is about 70 degrees" versus saying "it's exactly 72.4 degrees." That extra bit of data changes how you design your circuit. Engineers call these "precision resistors," and they almost always have a tolerance of 1% or lower. Usually, you’ll see a brown band at the end, signifying that 1% tightness.

Cracking the code without losing your mind

Let’s be real: memorizing "Bad Beer Rots Our Young Guts But Vodka Goes Well" (the classic mnemonic) is fine, but applying it to a tiny ceramic cylinder under a magnifying glass is a different story.

To read a 5 band resistor colour code, you have to hold it the right way. This is the part that trips everyone up. Look for the group of bands that are closer together. That’s your starting point—the left side. The band that sits slightly off by itself on the right? That’s your tolerance.

👉 See also: Setting Music as a Ringtone for iPhone: Why Is It Still This Hard?

- The First Band: This is your first significant digit. If it’s Red, that’s a 2.

- The Second Band: This is the second digit. Let's say it’s Violet. That’s a 7.

- The Third Band: Here is where it differs from the 4-band version. This is your third significant digit. If it’s Black, it’s a 0. So far, we have "270."

- The Fourth Band: This is the Multiplier. This is the power of ten you multiply your three digits by. If this band is Brown, you multiply by 10.

- The Fifth Band: The Tolerance. A Brown band here means ±1%.

So, a Red-Violet-Black-Brown-Brown resistor is a 2,700 ohm (or 2.7kΩ) resistor with a 1% tolerance.

The tricky bits: Gold and Silver multipliers

Sometimes you'll see Gold or Silver in the fourth position. Don't panic. While they usually represent tolerance in 4-band resistors, in the multiplier position of a 5-bander, they mean you're dealing with sub-ohm values.

Gold means you divide by 10 (or multiply by 0.1).

Silver means you divide by 100 (or multiply by 0.01).

If you see a 5-band resistor that ends in a weird way, or has bands that seem out of order, it might actually be a 6-band resistor. Those add a temperature coefficient stripe at the very end, which tells you how much the resistance will drift as the component gets hot. But honestly? Unless you’re designing aerospace hardware or high-end medical equipment, you probably won't need to worry about the sixth band today.

Common mistakes that'll ruin your circuit

Mistaking Brown for Red under poor lighting is the number one cause of circuit failure in hobbyist labs. I’ve done it. Everyone has. Under a warm desk lamp, a brown band can look suspiciously like a dark red. If you mistake a 100-ohm resistor for a 200-ohm one, your LED might be dim, but if you go the other way, you might just smell smoke.

Another "gotcha" is reading the resistor backward. If you read a 1% resistor from right to left, you're going to get a value that doesn't exist in the standard E-series (like the E96 or E192 series). If the numbers you're getting seem completely random and don't match any standard value you find online, flip the resistor over. You're likely looking at the tolerance band first.

Quality and the "Blue" Resistor Mystery

You might notice that most 5-band resistors have a blue or light-blue body, while the 4-band ones are usually tan or beige. This isn't a hard rule, but it's a common industry convention. The blue body usually signifies a metal film resistor. Metal film resistors are quieter (they generate less thermal noise) and more stable than the carbon film resistors found in the tan-colored 4-band variety.

When you're shopping on sites like Digi-Key or Mouser, you'll see these referred to as "Through-Hole Resistors - Fixed." If the project specs call for "1% Metal Film," they are almost certainly expecting you to use the 5 band resistor colour code to verify your parts.

Actionable next steps for your workbench

Stop squinting. Seriously. If you're going to work with these regularly, do these three things:

- Buy a decent digital multimeter (DMM). Even a cheap one is more accurate than your eyes at 11 PM. If you aren't 100% sure about the bands, probe it.

- Invest in a "third hand" tool with a magnifying glass. The bands on 1/8th watt or 1/4 watt resistors are microscopic. A 5x magnification makes the difference between seeing "Brown" and "Black" incredibly clear.

- Keep a printed E96 series chart on your wall. Precision resistors follow specific mathematical patterns. If your calculation doesn't match a value on the E96 chart, you've probably misread a band.

The 5 band resistor colour code isn't meant to be a barrier to entry. It's a tool for better engineering. Once you get used to looking for that third digit, you'll find that your circuits are more predictable, your timing is more accurate, and you'll spend a lot less time wondering why your "perfect" design is behaving like it has a mind of its own. Grab your multimeter, find a scrap board, and start practicing. It becomes second nature faster than you'd think.