Numbers are weird. We use them to buy groceries, track our steps, and tell the time, but most of us stop thinking about what they actually are the moment we leave high school. Honestly, that’s a mistake. If you’ve ever tried to calculate the diagonal of a square or wondered why pi never ends, you’ve bumped into the messy, beautiful reality of rational and irrational numbers.

It’s not just academic fluff.

The distinction between these two groups changed how we see the universe. It literally broke the minds of ancient Greek philosophers. They hated the idea that some numbers couldn't be tamed.

What's the deal with rational and irrational numbers anyway?

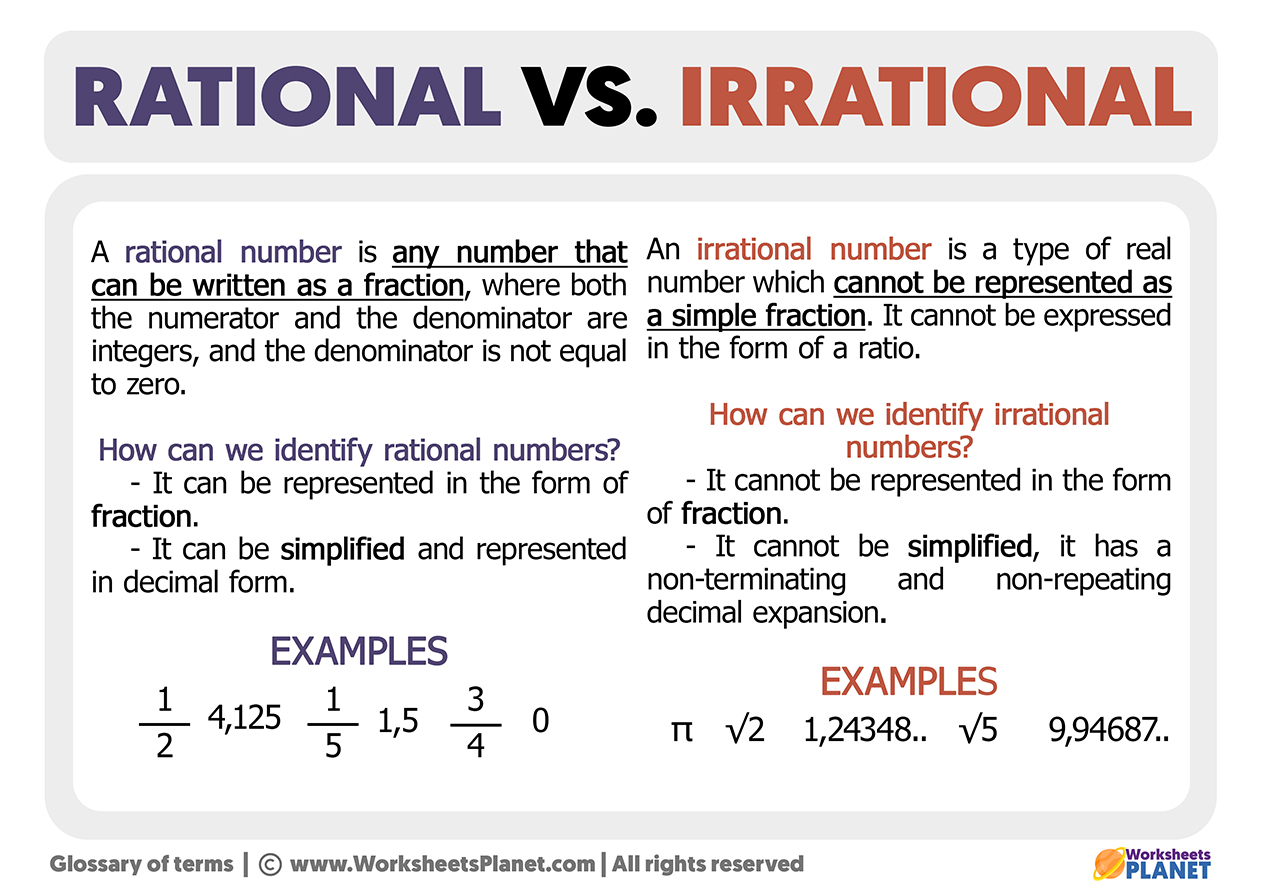

At its most basic, a rational number is anything you can write as a simple fraction. Think $1/2$ or $3/4$ or even $5/1$ (which is just $5$). If you can express it as a ratio of two integers—where the bottom number isn't zero—it's rational. The word "rational" actually comes from "ratio." It's not about the number being "sane" or "logical," though it feels that way because these numbers behave themselves. They either end (like $0.5$) or they repeat in a predictable pattern (like $0.333...$).

Irrational numbers are the rebels.

You cannot write them as a fraction. Ever. If you try to write them as a decimal, they go on forever without ever settling into a repeating loop. It’s total chaos, mathematically speaking.

The most famous one is $\pi$. You know it as $3.14$, but that’s a lie. It’s an approximation. In reality, it’s $3.14159265...$ and it keeps going into infinity. There is no "end" to the digits of pi. Computers have calculated it to trillions of places, and we still haven't found a pattern. This is why rational and irrational numbers are so fundamentally different: one is about precision and limits, and the other is about the infinite.

The Pythagorean Scandal

Legend has it that a guy named Hippasus, a follower of Pythagoras, was the one who discovered irrational numbers. The Pythagoreans were a bit of a cult. They believed "all is number" and that the entire universe could be explained through whole numbers and their ratios. They thought everything was clean.

Then Hippasus looked at a square with sides of length $1$.

Using the Pythagorean theorem, he tried to find the length of the diagonal. It turned out to be $\sqrt{2}$. He realized $\sqrt{2}$ couldn't be written as a fraction. This was heresy. According to some stories, the other Pythagoreans were so upset by this "irrational" discovery that they took Hippasus out on a boat and threw him overboard.

Talk about a tough crowd.

How to spot them in the wild

You’ve probably got a better handle on rational numbers than you think. Every whole number is rational. Zero is rational. Even negative numbers like $-10$ are rational because you can write them as $-10/1$.

But the irrationals are sneakier.

- Square roots of non-perfect squares: $\sqrt{2}$, $\sqrt{3}$, $\sqrt{5}$. If the number inside the root isn't a perfect square (like $4, 9, 16$), the result is irrational.

- Mathematical constants: $\pi$ (Pi) for circles, $e$ (Euler's number) for growth, and $\phi$ (the Golden Ratio) for aesthetics and nature.

- Decimals that never repeat: $0.1010010001...$ notice how the pattern changes? That's irrational.

Most of the numbers we use in daily life—bank balances, speed limits, recipes—are rational. We like them because they are manageable. We can round them. But the universe doesn't care about our need for clean endings. When you're dealing with physics, engineering, or high-level computer science, the irrational stuff is where the real action is.

The Density Property (Or: Why there's always more)

Here is a mind-bender. Between any two rational numbers, there is another rational number. Always.

If you take $0.1$ and $0.2$, you can find $0.15$. Between $0.1$ and $0.11$, you find $0.105$. You can do this forever. This is called "density." It makes the number line feel full. But here’s the kicker: even though there are infinitely many rational numbers, there are actually "more" irrational numbers.

Mathematicians like Georg Cantor proved that there are different sizes of infinity. The infinity of rational numbers is "countable," but the infinity of irrational numbers is "uncountable." If you were to drop a pin randomly on a number line, the mathematical probability that you'd hit a rational number is actually zero.

The line is mostly made of the "irrational" gaps.

Why this matters for technology

In the digital world, everything is eventually chopped into bits. Computers are inherently rational machines. They deal in discrete values—ones and zeros. This creates a problem when we try to simulate the real world, which is full of irrationality.

When a programmer calculates the area of a circle, they have to "truncate" pi. They might use 15 decimal places. For most things, that's fine. If you use 39 digits of pi, you can calculate the circumference of the observable universe with an error no greater than the width of a single hydrogen atom.

But in things like GPS or high-frequency trading, those tiny rounding errors can stack up. This is why understanding the difference between rational and irrational numbers isn't just for math class. It’s about how we translate the infinite, messy physical world into the limited, structured digital world.

Common misconceptions you should ignore

People often think that a very long decimal is irrational. Nope.

✨ Don't miss: Boston Dynamics Robot Dancing: Why Those Viral Videos Are Actually Genius Engineering

If you have $0.123123123$ going on forever, it's just $41/333$. It's rational. The length doesn't matter; the pattern does. If it repeats, it's rational. If it ends, it's rational.

Another weird one is people thinking $\pi$ equals $22/7$. It doesn't. $22/7$ is $3.1428...$ while $\pi$ is $3.1415...$. It's a great shortcut for a 7th-grade math test, but it's fundamentally wrong. One is a fraction (rational) and the other is a constant (irrational).

Practical steps for mastering the number line

If you're trying to get a better handle on this, or maybe helping a kid with homework, stop focusing on the definitions and start looking at the "why."

- Test for fractions: Can you write it as a fraction? If yes, it's rational. If you find yourself needing to use a symbol like $\pi$ or $\sqrt{}$ to express the "exact" value, it’s likely irrational.

- Look for the "End": Does the decimal stop? If it stops (terminates), it is always rational.

- Check the pattern: If it doesn't stop, is it doing the exact same thing over and over? $0.666...$ is just $2/3$. Rational.

- Accept the "Unknowable": Understand that for irrational numbers, we can only ever use approximations in the real world. We can never write the "whole" number down because there is no whole number to write.

The world is built on these two pillars. We need the rational numbers to keep things organized, to build houses, and to trade currency. But we need the irrational numbers to understand circles, growth, and the true underlying geometry of space. Without both, our understanding of reality would be incomplete.

Instead of seeing irrational numbers as "problems" to be solved, see them as the parts of math that refuse to be put in a box. They are the evidence that math isn't just a human invention—it's a discovery of something much larger than us. Next time you see a square root, remember Hippasus. Respect the chaos.

Start by identifying the numbers in your own life. Your height? Likely rational (or at least measured that way). Your debt-to-income ratio? Rational. The relationship between the diameter of your coffee cup and its rim? Beautifully, stubbornly irrational.

Key Takeaways for Daily Application:

- Always use the formal symbol ($\pi$ or $\sqrt{2}$) in precise calculations until the very last step to avoid "rounding drift."

- Recognize that "irrational" in math doesn't mean "illogical"—it means "not a ratio."

- When coding or using spreadsheets, be aware that the computer is approximating irrational values, which can lead to "floating-point errors" in long-term data sets.