Imagine sticking your head out of a train window while it’s pouring rain and the engine is screaming at 60 miles per hour. Most of us would just get a face full of soot and a cold. But for J.M.W. Turner, that was basically a Tuesday in 1844. He didn't just see a locomotive; he saw a monster ripping through the soul of England.

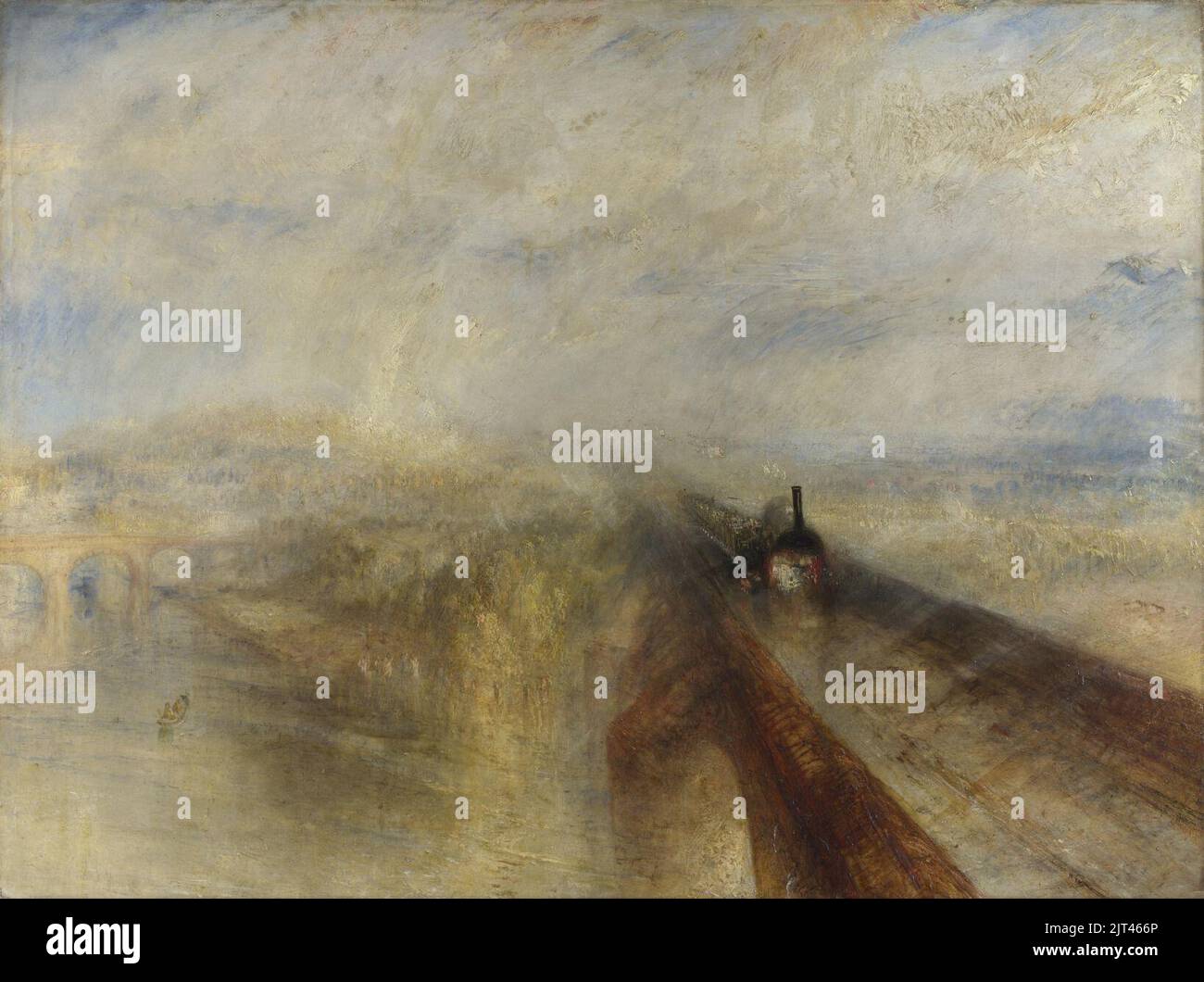

When Rain Steam and Speed first showed up at the Royal Academy, people thought Turner had finally lost it. Critics joked about "jam tarts" being smeared on a canvas. Honestly, it's easy to see why. The painting is a blurry, golden, violent mess of oil that looks more like a modern abstract piece than something from the Victorian era. But look closer. This isn't just about a train. It’s about the exact moment the world changed forever.

The Bridge, the Beast, and the Brunel Factor

Most people don't realize that Rain Steam and Speed is actually a very specific location. We aren't looking at some imaginary dreamscape. This is the Maidenhead Railway Bridge. It’s crossing the Thames, and it was designed by none other than Isambard Kingdom Brunel, the rockstar engineer of the 19th century.

At the time, this bridge was a technical marvel. It had the flattest brick arches in the world. People literally thought it would fall down the second a train touched it. Turner, being the absolute madman he was, chose this exact symbol of "new tech" to be his centerpiece.

- The Perspective: You’re looking East toward London.

- The Train: It’s likely a "Firefly" class locomotive.

- The Speed: While 60 mph sounds slow now, in 1844, it was terrifying. It was faster than a galloping horse. It was faster than anything humans had ever experienced.

Turner uses this aggressive diagonal line—the viaduct—to slice right through the canvas. It’s like the train is about to burst out of the frame and hit you in the face.

💡 You might also like: How to Watch The Wolf and the Lion Without Getting Lost in the Wild

That Tiny Hare Nobody Can See Anymore

There’s a secret in the bottom right. Or at least, there used to be a clearer one. If you squint at the original in the National Gallery, you might miss it because the paint has become transparent over the last 180 years. It’s a hare. A tiny, frantic rabbit-like creature running for its life on the tracks right in front of the engine.

Why a hare?

Some art historians, like John Gage, think it’s Turner’s way of showing that nature is about to get crushed. The hare was the fastest thing in the British countryside for thousands of years. Then, suddenly, this iron horse shows up. It’s a race the hare is definitely going to lose. It’s kinda dark when you think about it.

But there’s another layer. To the left of the massive railway bridge, Turner painted a tiny, old stone road bridge. You can see a little boat on the water and a guy ploughing a field in the distance. These are the "old ways." They’re slow. They’re quiet. And they are being completely drowned out by the hiss of the steam and the roar of the GWR.

📖 Related: Is Lincoln Lawyer Coming Back? Mickey Haller's Next Move Explained

Why the "Head Out the Window" Story Matters

There’s this famous anecdote about a lady on a train during a storm. She saw a "gentleman" opposite her open the window, lean out into the driving rain, and stay there for nearly ten minutes. Later, she saw the painting at the Academy and realized she’d been sitting across from Turner.

Is it true? Hard to say for sure.

But it feels true. Turner was obsessed with "the sublime"—the idea that nature is so big and powerful it’s actually scary. He supposedly had himself tied to a ship’s mast during a storm to paint Snow Storm - Steam-Boat off a Harbour's Mouth. Leaning out of a train window to feel the "speed" is exactly the kind of thing he’d do.

He wasn't trying to paint a photo-realistic train. He was trying to paint the feeling of being on that train. The way the rain smears against the glass. The way the steam from the funnel (which he painted as three distinct puffs to show movement) mixes with the clouds.

👉 See also: Tim Dillon: I'm Your Mother Explained (Simply)

The Painting That Predicted the Future

It’s crazy to think that Rain Steam and Speed was painted decades before the French Impressionists like Monet or Pissarro were even a thing. Turner was doing the "blurry light" thing way before it was cool.

He used a palette knife to scrape paint across the surface. He used his thumbs. He probably used his spit. The result is a texture that feels vibrating and alive.

If you look at the engine, it’s not a crisp black machine. It’s a glowing, dark shape with a hint of fire in its belly. Turner knew that the Industrial Revolution wasn't just about gears and coal; it was about energy.

What You Should Do Next

If you want to actually "get" this painting, don't just look at a digital thumbnail. It doesn't work.

- Visit the National Gallery: If you're ever in London, go to Room 34. Stand about ten feet back from the canvas, then slowly walk toward it. Watch how the train "appears" out of the gold mist.

- Look for the 1859 Engraving: Since the hare is fading, find a high-res scan of Robert Brandard's engraving. He worked with Turner and clarified those tiny details that the oil paint has since swallowed up.

- Check the Weather: Next time you’re on a train and it’s raining, turn off your phone. Look out the window and try to see the landscape as a blur of color rather than a series of objects. That’s the "Turner Vision."

Honestly, Rain Steam and Speed is one of those rare artworks that gets better the more you know about the history. It’s not just a pretty picture of a train; it’s a eulogy for the old world and a frantic, messy welcome for the new one.

To see how this fits into the bigger picture of 19th-century art, you might want to look into Turner's other "tech" masterpiece, The Fighting Temeraire. It’s the flip side of this coin—a majestic old warship being towed to its scrap heap by a tiny, ugly steam tug. Between those two paintings, Turner basically told the entire story of the 1800s.