When we talk about the 2005 Atlantic hurricane season, everyone remembers the images of the Superdome or the broken levees. But if you look at the technical side of the disaster, the story of the radar for hurricane katrina is actually one of the most stressful tech dramas in meteorological history. It’s easy to assume that because we have giant satellite dishes and Doppler tech, we see everything coming with perfect clarity.

Honestly? That’s not what happened.

By the time Katrina was churning toward the Gulf Coast, the National Weather Service was leaning hard on a network of ground-based radars that were essentially staring down a monster. You’ve got to understand that radar isn’t just a "camera" for rain. It’s a radio wave system that has to survive the very thing it’s trying to measure.

The Slidell Radar vs. The Storm

The most famous piece of hardware in this whole saga was the WSR-88D radar located in Slidell, Louisiana. This was the primary radar for hurricane katrina coverage for the New Orleans area. In the weather world, we call these NEXRAD units. They are massive, powerful, and usually incredibly reliable.

But here’s the thing. Radar is basically a sitting duck during a Category 5 landfall.

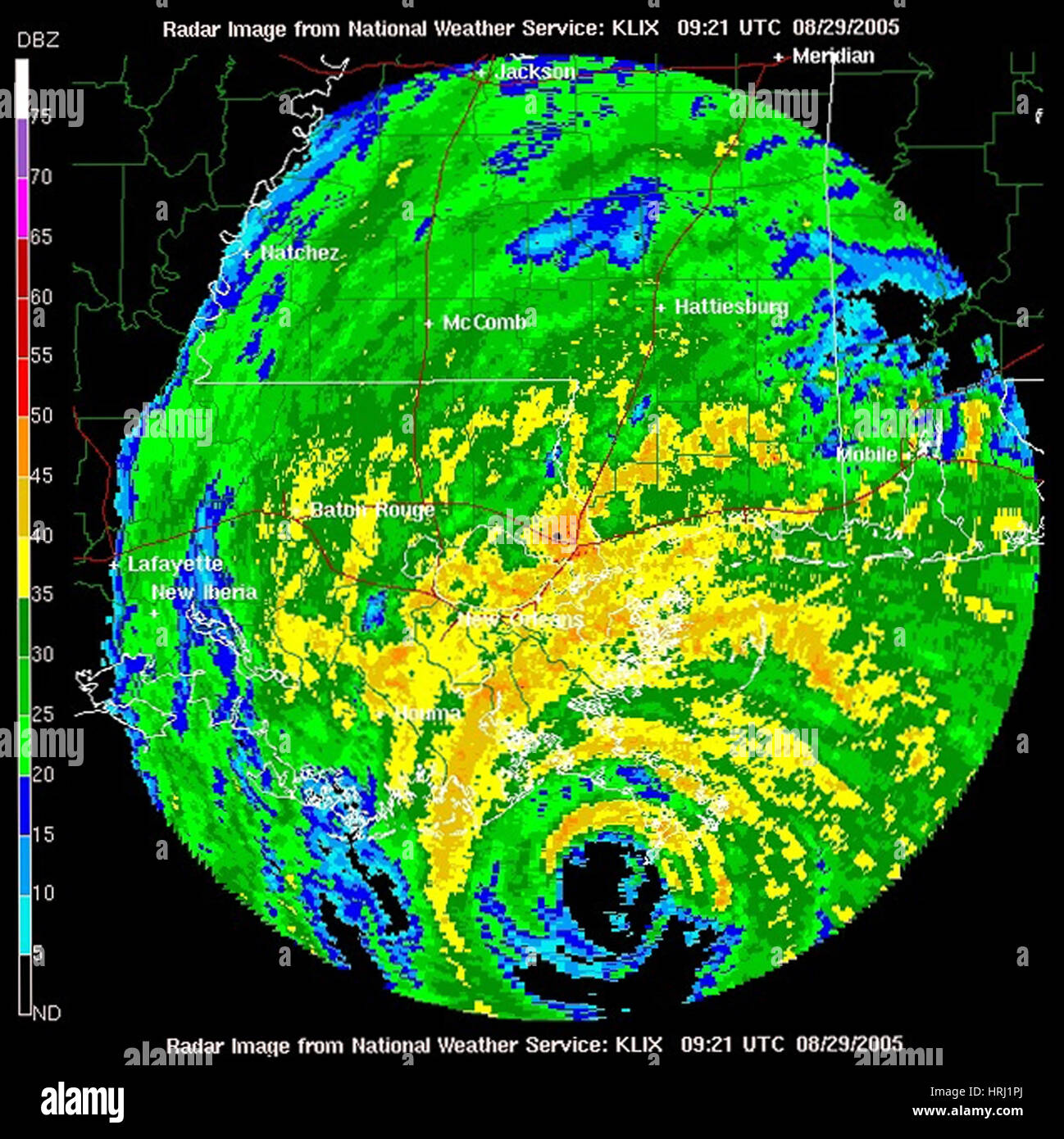

As Katrina’s eyewall approached the coast on the morning of August 29, the Slidell radar (identified as KLIX) was feeding critical data back to forecasters. It was showing the "eyewall replacement cycle"—that weird phenomenon where a storm develops a second, outer eye and then collapses the inner one, often growing the storm's physical size even if the peak wind speeds drop a tiny bit.

✨ Don't miss: Why Your Fitbit Time is Wrong and How to Change a Fitbit Time Without Losing Your Mind

Then, the data stopped.

Around 9:00 AM, the Slidell radar went offline. It didn't just "glitch." The storm literally tore it apart or knocked out the communications and power infrastructure supporting it. This happens more often than you'd think. When the most important radar for hurricane katrina went dark, forecasters were suddenly "blind" in the very moment the surge was hitting the Rigolets and Lake Borgne.

Flying into the Eye: Airborne Radar

When the ground stations fail, the burden shifts to the Hurricane Hunters. NOAA’s WP-3D Orion aircraft are basically flying laboratories. They carry two different types of radar systems:

- Lower Fuselage (LF) Radar: This scans horizontally to show the rain bands and help the pilots navigate.

- Tail Doppler Radar (TDR): This scans vertically, like a deli slicer, to get a 3D cross-section of the storm's wind field.

During Katrina, these planes were the only reason we knew the storm was actually weakening in terms of pure wind speed but expanding in terms of its "wind field." Even though the peak winds dropped from 175 mph to around 125 mph before landfall, the radar for hurricane katrina measurements from these planes showed that the storm's "energy" was now spread over a much larger area.

That’s a huge detail. Most people thought because it was a "Category 3" at landfall, the danger was less. The radar told a different story: the storm surge was already baked in. The water was already moving.

What Most People Get Wrong About Radar Data

You might think radar is what tells us a hurricane is coming. Kinda, but not really.

Radar has a limited range. For the WSR-88D units on the ground, you’re looking at about 250 miles for precipitation and even less for high-quality wind data. For most of Katrina’s life in the Gulf, it was tracked by satellites—specifically GOES-12.

📖 Related: What is c in mc2 and Why It’s the Speed Limit of the Universe

Radar only becomes the "star" when the storm is close enough to hit with a beam. This is called "landfall mode."

The real value of the radar for hurricane katrina wasn't just seeing the rain; it was the "velocity" data. By using the Doppler shift, meteorologists could see how fast the wind was moving toward or away from the radar dish. This is how they spotted the small tornadoes spinning off in the outer bands in Mississippi and Alabama.

Why the "Blind Spots" Mattered

When KLIX in Slidell went down, the NWS had to "mosaic" data from other radars. They used:

- KMBT in Mobile: This radar stayed up longer and caught the massive surge hitting the Mississippi coast.

- KLCH in Lake Charles: This was looking at the "back side" of the storm.

- KDGX in Jackson: This was crucial for tracking Katrina as it moved inland and stayed a hurricane for an incredibly long time.

But these radars are far away. Because the Earth is curved, a radar beam from Jackson, Mississippi, is actually looking thousands of feet above the ground by the time it reaches New Orleans. You miss the "low-level" stuff. You miss the exact moment the levees are being overtopped because you’re literally looking over the top of the event.

Satellite Radar: The Space Perspective

In 2005, we were also using the Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission (TRMM) satellite. This thing was a beast. It carried the first space-borne precipitation radar.

While ground radar for hurricane katrina was fighting for its life, TRMM was looking down from space and seeing "hot towers." These are massive thunderstorms in the eyewall that reach way up into the atmosphere. When you see hot towers on a radar, you know the storm is about to intensify.

TRMM caught these towers while Katrina was in the Gulf, giving the National Hurricane Center a heads-up that this wasn't just a normal storm—it was a "deep" system with an incredibly efficient heat engine.

🔗 Read more: That Coinbase verification code text scam is getting smarter—how to spot the trap

Lessons We Actually Learned (Actionable Insights)

If you live in a hurricane-prone area today, the legacy of the radar for hurricane katrina affects you every time a storm forms. The technology has changed because of the failures and successes of 2005.

1. Dual-Polarization is now standard.

Back in 2005, radars sent out one horizontal beam. Now, we use "Dual-Pol," which sends out both horizontal and vertical pulses. This allows meteorologists to tell the difference between rain, hail, and "debris." If a radar in 2026 sees a "debris ball," it means a tornado is actually on the ground throwing houses into the air. We didn't have that clarity during Katrina.

2. Redundancy is the new priority.

The fact that the Slidell radar failed led to a massive push for better backup power and hardened "radomes" (the soccer-ball-looking shells that protect the dish). Today, the NWS has better protocols for "handing off" coverage between stations so that there's no "blind" period during landfall.

3. Mobile Radar Units.

We now see "Doppler on Wheels" (DOW) and other mobile radar trucks being deployed ahead of storms. During Katrina, these were mostly research tools. Now, they are often used to fill the gaps when a fixed ground station inevitably gets knocked out by 140 mph winds.

4. Don't trust the "Category" alone.

The radar data from Katrina proved that a "weakening" storm can still be a "growing" disaster. If you're looking at a radar map and see the eye getting bigger and more "ragged," don't assume the danger is over. A bigger eye often means a bigger wind field and a more massive storm surge.

If you're tracking a storm today, the best thing you can do is look for "Velocity" products on your radar app, not just the "Reflectivity" (the green/yellow/red rain colors). The velocity tells you where the wind is actually screaming. And remember, if the radar image in your area suddenly "freezes" or stops updating during a hurricane, it's a sign that the local infrastructure has failed—and that's your cue to be in your safe space, not looking out the window.

The radar for hurricane katrina was a tool pushed to its absolute limit. It gave us the data to save thousands through early warnings, even if the hardware itself couldn't survive the final impact. Today's systems are faster and smarter, but the physics remains the same: you can't manage what you can't measure.