It is often called the "Rach 3." To some, it’s the "Everest of piano concertos." To others, it’s just forty-odd minutes of pure, unadulterated masochism set to a D-minor key signature. If you’ve ever watched a pianist finish the Rachmaninoff Piano Concerto 3, you’ve probably noticed they look like they just ran a marathon while solving a Rubik's cube in their head. They are drenched. Exhausted. Sometimes, they look genuinely traumatized.

There is a reason for that.

Sergei Rachmaninoff didn't write this piece to be "nice." He wrote it in 1909 as a calling card for his first American tour. He needed something big. Something flashy. Something that would prove to the New York crowds that he wasn't just another Russian import, but a titan of the keyboard. Honestly, he might have overdone it. The piece contains more notes per second than almost anything else in the standard repertoire. It’s a dense, thick, lyrical, and violent forest of sound that has swallowed many careers whole.

The "Elephant" in the Room

Musicians sometimes call this concerto the "Elephant." That’s not a compliment to its grace; it’s a nod to its size and the sheer weight of the notes. You have to move a lot of air to make this piece work.

The technical hurdles in the Rachmaninoff Piano Concerto 3 are legendary. We aren't just talking about playing fast. Plenty of people can play fast. We are talking about massive chordal stretches that require hands the size of dinner plates. Rachmaninoff himself had a legendary reach—rumor has it he could span a 13th on the keys. For the rest of us mortals with average-sized hands, playing the Rach 3 involves a lot of "faking" or clever redistribution of notes just to keep from snapping a tendon.

Think about the cadenza in the first movement. Rachmaninoff actually wrote two versions. One is the "regular" one (the toccata style), which is already harder than 90% of what Mozart ever wrote. Then there’s the ossia cadenza. It is a massive, thundering block of chords that sounds like a cathedral falling down. For decades, pianists avoided the bigger version because it was deemed "unplayable" or just too "thick." Vladimir Horowitz, the man who basically owned this concerto in the mid-20th century, famously stuck to the lighter version. It wasn't until later players like Lazar Berman or Yefim Bronfman started regularly tackling the ossia that it became a benchmark for "alpha" pianists.

What People Get Wrong About the Difficulty

You’ll hear people say the Rach 3 is hard because of the finale. The third movement is a sprint. It’s rhythmic, it’s percussive, and it requires a level of stamina that most people simply don't possess.

💡 You might also like: How to Watch The Wolf and the Lion Without Getting Lost in the Wild

But that’s not the real trick.

The real difficulty of the Rachmaninoff Piano Concerto 3 is the texture. Rachmaninoff was a master of "inner voices." While your thumbs and pinkies are screaming through a melody, your middle fingers are often tasked with playing complex, rolling accompaniment figures that need to be heard but not too heard. It’s like trying to pat your head, rub your stomach, and recite the alphabet backward while someone throws bricks at you.

Gary Graffman, a legendary pianist and teacher at Curtis, famously said he shouldn't have tried to learn it as a student. It’s a piece that demands maturity. If you play it too fast, it becomes a blur. If you play it too slow, it becomes "soupy" and sentimental. Finding that middle ground—the "Slavic soul" without the melodrama—is where most performers fail.

The "Shine" Effect and Pop Culture

Most people outside the classical world know this piece because of the 1996 movie Shine. The film tells the story of David Helfgott, a pianist who suffers a mental breakdown while trying to master the Rach 3.

It’s a great movie.

But it sort of created this myth that the concerto is cursed. It’s not. It’s just very, very difficult. The film portrays the music as a literal breaking point for the human mind. While that makes for great cinema, the reality is more about physical mechanics and memory. The sheer volume of notes means that if your focus slips for even three seconds, the whole thing can collapse like a house of cards. You can't "autopilot" the Rachmaninoff Piano Concerto 3. The moment you stop thinking, you're dead.

📖 Related: Is Lincoln Lawyer Coming Back? Mickey Haller's Next Move Explained

A Disaster of a Premiere?

Believe it or not, this piece wasn't an instant hit. When Rachmaninoff premiered it in New York in 1909 with the New York Symphony Society, the reaction was... fine. Just fine.

He dedicated it to Josef Hofmann, who was considered the greatest pianist of the era. Hofmann never played it. Not once. He said it "wasn't for him" or that the hand stretches were too much. Imagine writing a masterpiece for your friend and they just give you a "thanks, but no thanks."

It took Vladimir Horowitz to really put this piece on the map. In the 1920s and 30s, Horowitz turned it into a high-wire act. He played it with a ferocity and a percussive edge that made people realize this wasn't just a "pretty" Romantic concerto. It was a war machine. Rachmaninoff himself supposedly heard Horowitz play it and said, "He swallowed it whole." After that, Sergei basically stopped playing his own concerto in public as much. He knew he’d been beaten at his own game.

Why It Still Matters in 2026

We live in an age of MIDI and perfectly edited recordings. You can go on YouTube and find a hundred child prodigies playing the Rachmaninoff Piano Concerto 3 at 150% speed.

So why do we still care?

Because you can't fake the struggle. In a live concert hall, the Rach 3 is a physical drama. You see the sweat. You see the pianist fighting against the orchestra. Rachmaninoff’s orchestration is famously "heavy." He uses the brass and the woodwinds like a blunt instrument. For a pianist to be heard over that wall of sound, they have to play with incredible power.

👉 See also: Tim Dillon: I'm Your Mother Explained (Simply)

It’s the ultimate test of human capability. We watch it for the same reason we watch the Olympics. We want to see if the person on stage can actually survive the 40-minute onslaught.

Navigating the Best Recordings

If you want to understand this piece, you can't just listen to one version. You need to hear the different philosophies of how to tackle the monster.

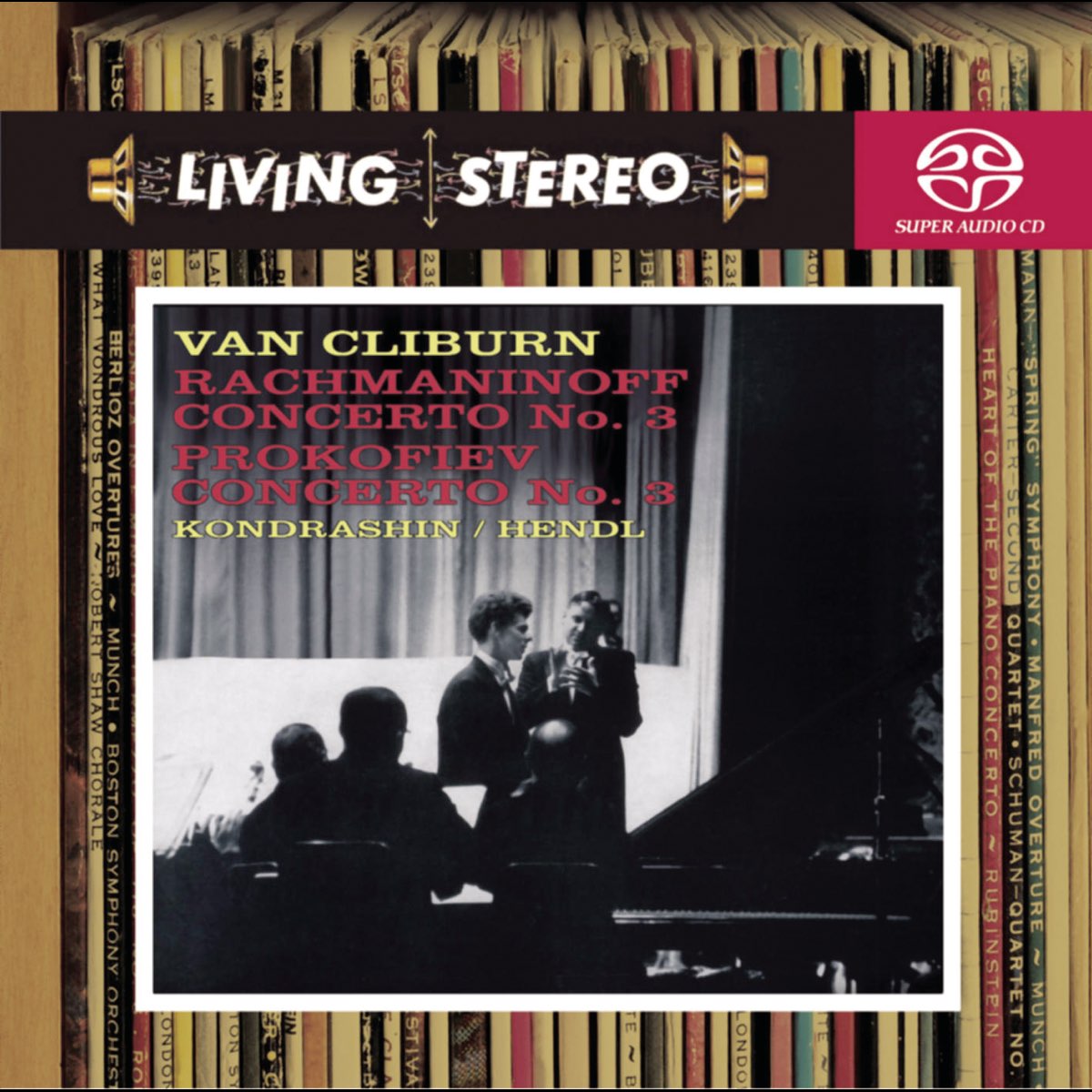

- Sergei Rachmaninoff (1939/40): Yes, the man himself recorded it. It is surprisingly fast. He doesn't linger on the "pretty" parts. It’s lean, rhythmic, and business-like. It’s a great reminder that the composer didn't want it to be "mushy."

- Vladimir Horowitz (1951 or 1978): The 1951 recording with Reiner is legendary for its demonic energy. The 1978 "Golden Jubilee" version is more controversial—he was older, and the technique was quirkier—but the drama is off the charts.

- Martha Argerich (1982): This is often cited as the "best" modern recording. Argerich plays it like she’s possessed. Her speed in the finale is genuinely frightening. It feels like the piano might actually catch fire.

- Yevgeny Kissin (various): If you want to hear every single note placed with crystalline perfection, Kissin is your man. It’s less "wild" than Argerich but incredibly impressive in its control.

Practical Insights for the Aspiring Listener

Don't try to "get it" all at once. The first time you hear the Rachmaninoff Piano Concerto 3, it might just sound like a wall of noise.

Focus on the opening. It’s a simple, haunting melody played in octaves. It sounds like a Russian folk song. Rachmaninoff claimed it just "wrote itself." Everything that happens for the next 40 minutes—all the chaos, the thunder, the lightning—comes from that one simple, quiet seed.

If you are a student thinking about learning it, honestly, check your reach first. If you can’t comfortably hit a 10th, you’re going to spend half your practice time figuring out how to roll chords without losing the beat. Start with his Preludes or the Second Concerto. The Third is a different beast entirely. It requires a level of independence between the hands that most people take a decade to develop.

Final Takeaway

The Rachmaninoff Piano Concerto 3 isn't just a piece of music; it's a physical and mental threshold. It represents the peak of the Romantic era's obsession with the "virtuoso as hero." When you listen to it, you aren't just hearing a melody. You are hearing a man trying to push the piano to its absolute breaking point.

Next Steps for Deepening Your Knowledge:

- Compare the ossia (heavy) cadenza and the standard (light) cadenza back-to-back. You can find "comparison" videos on most streaming platforms that highlight the structural differences.

- Listen to the Second Concerto immediately followed by the Third. Notice how the Second is about "the tune," while the Third is about "the development."

- Watch a filmed performance (like Yuja Wang or Denis Matsuev) rather than just listening. Seeing the hand movements is essential to understanding why this piece is so feared by professionals.

The Rach 3 remains the ultimate "boss fight" of the piano world. Whether you're a casual listener or a conservatory student, it demands respect. Just don't expect to feel "relaxed" after the finale. That's not the point. The point is to survive it.