You’ve heard them a thousand times. Even if you haven't sat in a hushed literature classroom since high school, quatrains are basically the soundtrack to your life. From the nursery rhymes that kept you quiet as a toddler to the Taylor Swift bridge that’s currently stuck in your head, these four-line blocks are the absolute backbone of Western writing.

What are quatrains in poetry?

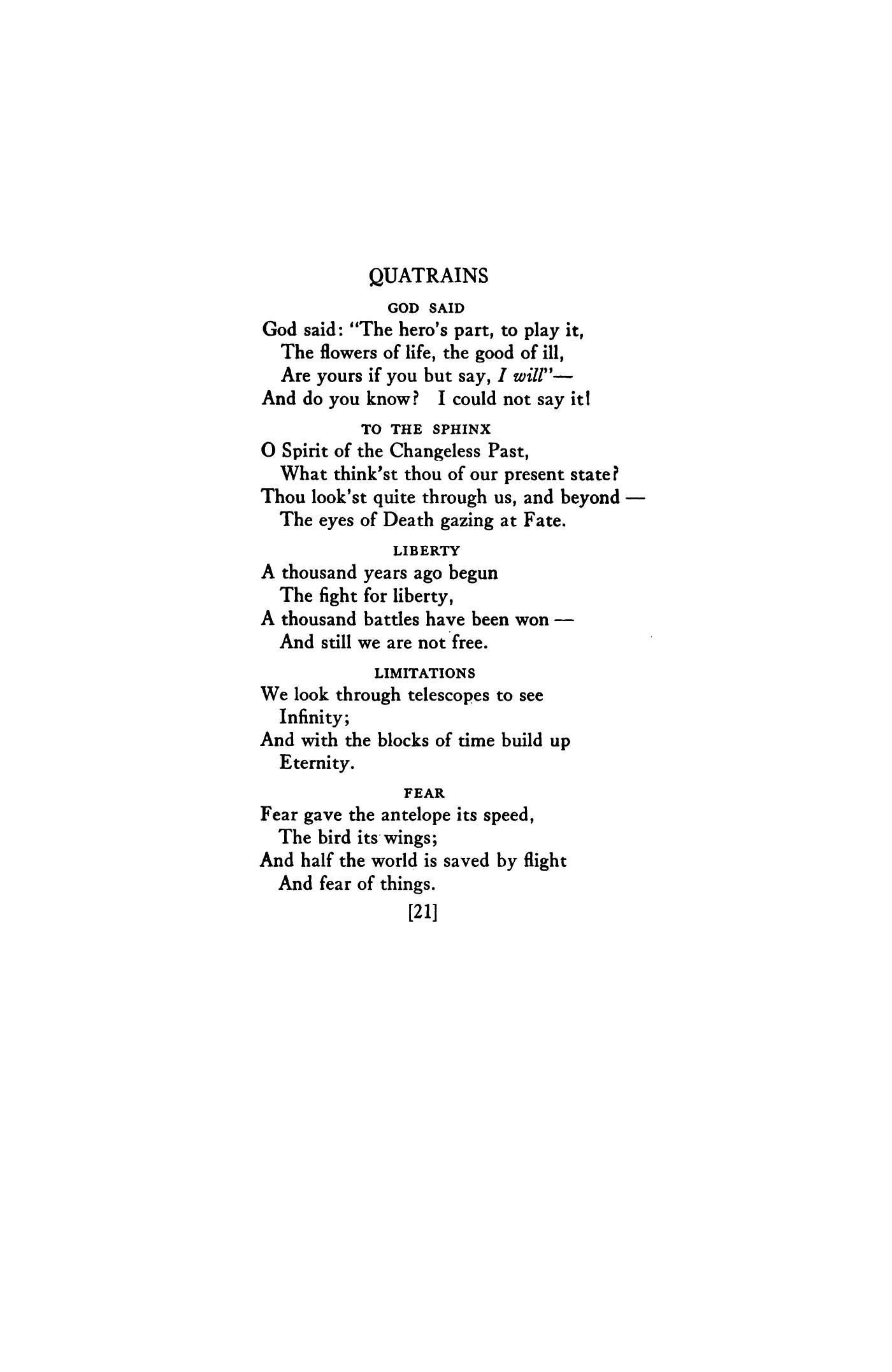

At its most basic level, a quatrain is just a stanza of four lines. That’s it. But calling it "just" four lines is like saying a burger is "just" meat and bread. It’s the architecture. It’s the way the rhyme carries the rhythm until your brain feels that satisfying click of a completed thought.

Honestly, the quatrain is the workhorse of the poetic world. While the couplet (two lines) feels too fast and the sestet (six lines) can get a bit wordy, the quatrain is "just right." It’s stable. It’s symmetrical. It gives a poet enough room to set a scene, twist the plot, and resolve the tension without losing the reader in a sea of text.

The DNA of the Four-Line Stanza

Most people think poetry has to be this high-brow, complicated mess of metaphors. It isn't. Quatrains work because they mirror how we naturally speak and breathe. Think about it. You make a statement. You qualify it. You add a detail. You wrap it up. Four steps.

The magic happens in the rhyme scheme. You’ve probably seen these labeled with letters like AABB or ABAB. That’s just a shorthand way of saying which lines rhyme with each other. In an AABB setup, the first two lines rhyme, and the last two lines rhyme. It’s punchy. It’s what you find in "The Rime of the Ancient Mariner" by Samuel Taylor Coleridge.

Then you have the ABAB pattern, often called "alternate rhyme." This is the sophisticated cousin. It keeps the reader leaning in because you have to wait an extra line for the payoff of the rhyme. It creates a weaving effect.

The Rhymes That Actually Matter

If you want to understand how these things function in the wild, you have to look at the specific flavors they come in. Not all quatrains are built the same way.

The Heroic Stanza

This one is for the drama. Written in iambic pentameter—that "da-DUM da-DUM da-DUM" heartbeat rhythm—the Heroic Stanza uses an ABAB rhyme scheme. Thomas Gray’s "Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard" is the gold standard here. It feels heavy. It feels important. When you read it, you can almost hear the slow tolling of a bell.

👉 See also: Billie Eilish Therefore I Am Explained: The Philosophy Behind the Mall Raid

The Ballad Meter

This is the one you actually know, even if you don't know the name. It’s the rhythm of "Amazing Grace" or the theme song to Gilligan’s Island. (Seriously, try singing the lyrics of one to the tune of the other; it works because they both use ballad quatrains).

Ballad meter usually alternates between eight syllables and six syllables. It’s catchy. It’s easy to memorize. This is why folk songs and hymns have relied on it for centuries. It’s built for the human ear to grab onto and never let go.

The Rubaiyat Stanza

Now, if you want something that feels a bit more exotic and haunting, you look at the AABA rhyme scheme. This was made famous in the English-speaking world by Edward FitzGerald’s translation of the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam.

The weird thing about AABA is that third line. It doesn’t rhyme. It hangs there, suspended, creating this tension that only gets resolved when the fourth line brings back the "A" rhyme. Robert Frost used this beautifully in "Stopping by Woods on a Snowy Evening." That unrhymed third line feels like a cold gust of wind before you pull your coat tighter in the final line.

Why Shakespeare Couldn't Quit Them

We can't talk about quatrains without mentioning the big guy. William Shakespeare didn't just write plays; he was obsessed with the sonnet. A Shakespearean sonnet is basically three quatrains followed by a tiny two-line couplet at the end.

The quatrains do all the heavy lifting. The first one introduces the problem (e.g., "I'm getting old"). The second one expands on it ("Everything beautiful eventually dies"). The third one brings the "turn" or the "volta" ("But your beauty won't fade as long as this poem exists").

By the time you get to the couplet, the quatrains have already convinced you of the poet's argument. They provide the logical steps of a feeling. Without the quatrain structure, a sonnet would just be a rambling list of complaints.

The Modern Secret: Pop Music is Just Quatrains

Stop reading for a second and think about your favorite song. Not the instrumental bits, but the verses.

✨ Don't miss: Bad For Me Lyrics Kevin Gates: The Messy Truth Behind the Song

"Every breath you take / Every move you make / Every bond you break / Every step you take."

That’s a quatrain. Specifically, it’s a Monorhyme quatrain (AAAA). It’s obsessive. It’s tight. It fits the theme of the song perfectly.

From Emily Dickinson—who basically wrote exclusively in quatrains because she loved the hymn-like structure—to Kendrick Lamar, the four-line unit is the universal constant. It’s the "byte" of information in the literary world. It’s small enough to handle but big enough to mean something.

Common Misconceptions About the Four-Line Form

A lot of people think quatrains have to rhyme. They don't.

While rhyming is the traditional way to glue a quatrain together, modern poets use "slant rhyme" (words that almost rhyme, like "bridge" and "grudge") or no rhyme at all. This is called enjambment when the thought spills over from one line to the next without a pause.

Another myth is that quatrains are "easy" or "for beginners." Just because a child can write a four-line poem about a cat doesn't mean the form is shallow. Some of the most devastatingly complex philosophy in history has been squeezed into quatrains. It’s the constraint that makes it difficult. Trying to fit the vastness of human grief or the complexity of quantum physics into forty syllables is like trying to fit an ocean into a glass. It requires a level of precision that free verse often lacks.

Getting Your Hands Dirty: How to Use Them

If you’re a writer, or just someone who wants to understand art better, you should try to spot these in the wild.

First, look for the "white space." If you see a poem broken into neat little blocks, count the lines. If it's four, you're looking at a quatrain.

🔗 Read more: Ashley Johnson: The Last of Us Voice Actress Who Changed Everything

Second, check the rhythm. Is it bouncy? Is it somber? Usually, the length of the lines tells you the "mood." Short lines feel urgent or light. Long lines feel intellectual or exhausted.

Third, look at the rhyme. Is it predictable? If it's AABB, the poet is likely trying to sound simple, folk-like, or perhaps even a bit sarcastic. If it's ABAB, they are aiming for a more balanced, classical feel.

The Actionable Takeaway for Readers

Understanding quatrains isn't just about passing a lit quiz. It's about recognizing the patterns that influence your emotions. When a songwriter shifts from a quatrain in the verse to a different structure in the chorus, your brain feels a physical shift in energy.

Next time you listen to a song or read a poem, do this:

- Identify the quatrain.

- Figure out the rhyme scheme (is it ABAB? AABB?).

- Ask yourself why the writer chose that specific "click."

- If you're a writer, try "The Frost Test": Write a four-line stanza where the third line doesn't rhyme (AABA). You'll find it’s much harder—and much more evocative—than a standard rhyme.

The quatrain survived the Middle Ages, the Renaissance, and the Industrial Revolution. It’ll survive the AI era, too, because it’s tuned to the frequency of the human heart. It’s the perfect container for an idea.

Practical Next Steps for Aspiring Poets:

- Start with Ballad Meter: Write a four-line stanza with 8 syllables in lines 1 and 3, and 6 syllables in lines 2 and 4. Use an ABCB rhyme scheme. This is the "easy mode" of poetry that actually sounds professional.

- Analyze "The Tyger" by William Blake: Look at how he uses AABB quatrains to create a sense of hammering or forging. It mimics the subject of the poem (a blacksmith-like creator).

- Practice Enjambment: Write a quatrain where the sentence doesn't end at the end of the line. Let it "fall" into the next line. This breaks the "nursery rhyme" feel and makes your writing sound more modern and sophisticated.

The quatrain is your most reliable tool. Use it to build something that lasts.