You've probably been there. You get a shipment of metal components in, and they look fine at first glance. Then you start the assembly line, and suddenly, the tolerances are off by a hair. Or maybe the burrs are just thick enough to snag a glove. It’s frustrating. It’s expensive. Honestly, it’s usually because the relationship between quality tool and stamping was treated like an afterthought rather than the backbone of the entire production run.

Most people think stamping is just about hitting metal with a heavy die. It isn't.

If the tool—the actual die set—isn't engineered with a "quality-first" DNA, you’re basically just gambling with every stroke of the press. We aren't just talking about making a part that matches a blueprint. We’re talking about repeatability. Can you make part number 500,000 look exactly like part number one? If the answer is "maybe," you don't have a quality process. You have a ticking time bomb.

The Brutal Reality of Tooling Degradation

Precision matters. A lot.

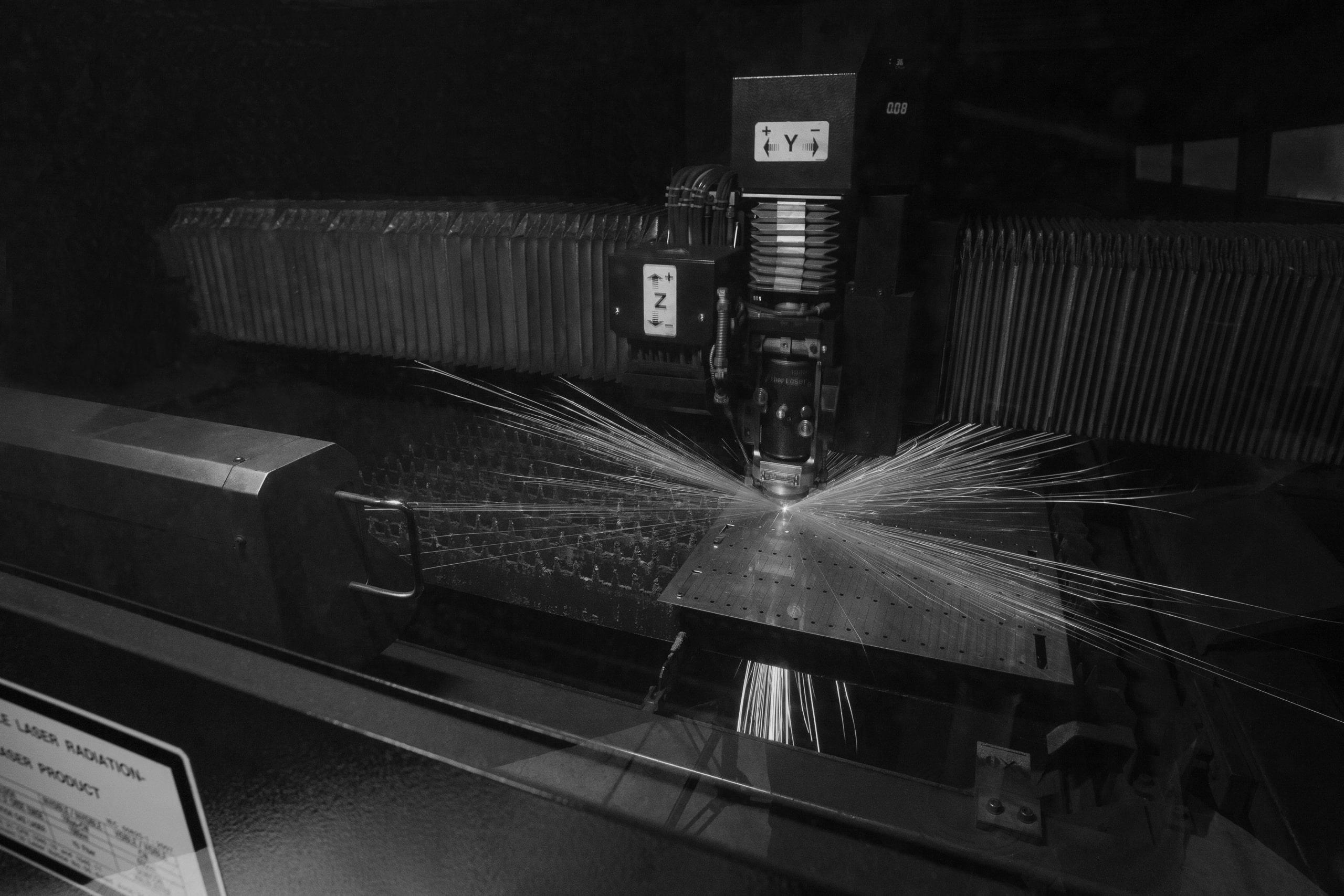

When we talk about quality tool and stamping, we have to talk about the physical reality of friction and heat. Every time that press comes down, the tool is dying a little bit. Metal-on-metal contact at high speeds creates heat that can actually change the molecular structure of the tool steel if it isn't managed.

Think about D2 or CPM-M4 tool steels. These aren't just random letters and numbers. They are specific alloys chosen for their "red hardness" and wear resistance. If your toolmaker used a cheaper A2 steel for a high-volume stainless steel run, you’re going to see "galling" almost immediately. This is where bits of the workpiece actually weld themselves to the tool. It ruins the finish. It creates scrap. It costs you a fortune in downtime.

Real quality starts in the tool room, not on the inspection table. If you're seeing inconsistent parts, the problem probably happened three months ago when the die was being heat-treated. If the Rockwell hardness isn't hit exactly—usually between 58 and 62 HRC for most high-production dies—the tool will either be too soft and deform or too brittle and literally shatter under the 200-ton load of the press.

Why Progressive Dies Are a Different Beast

Progressive stamping is a marvel of engineering. You feed a coil of metal in one end, and a finished part pops out the other. It’s fast. But it's also incredibly sensitive to error.

In a progressive die, the "strip" moves through multiple stations. One station pierces a hole. The next forms a flange. The next trims the edge. If the "pilot" pins—the little guides that keep the metal aligned—are off by even 0.001 inches, that error compounds at every single station. By the time the part reaches the cutoff, it's junk.

✨ Don't miss: Is US Stock Market Open Tomorrow? What to Know for the MLK Holiday Weekend

I’ve seen shops try to save money by skipping nitrogen manifolds in their dies. They use standard mechanical springs instead. Bad move. Mechanical springs lose their "oomph" over time and provide uneven pressure. Nitrogen springs provide a consistent, high-pressure hold-down that ensures the metal doesn't wrinkle during the draw. That is the "quality" part of quality tool and stamping that people often overlook because they’re trying to shave $5,000 off a $100,000 tool build.

You pay for it later. Always.

The Role of Material Science in Stamping Success

Let's get nerdy for a second. The metal you're stamping—whether it's 301 Stainless, 6061 Aluminum, or some high-strength low-alloy (HSLA) steel—has its own personality. It has a "grain." It has a yield strength.

If you try to bend a piece of metal "with the grain" (parallel to the direction it was rolled at the mill), it’s much more likely to crack than if you bend it "across the grain." High-quality tool design accounts for this. An expert tool designer will nest the parts on the strip at a specific angle to maximize material usage while ensuring the bends are structurally sound.

Then there’s the "springback" factor. Metal is elastic. When you bend it to 90 degrees, it wants to bounce back to 88 or 89 degrees. A quality tool is designed with "over-bend." You might actually bend it to 92 degrees so that when it settles, it hits that perfect 90. This isn't guesswork. It's calculated using complex simulations, but even then, a master toolmaker has to "tune" the die by hand during the first trial runs.

Sensoring: The Silent Guardian

In 2026, if your stamping die doesn't have sensors, you're living in the Stone Age.

Modern quality tool and stamping setups use "die protection" sensors. These are tiny proximity probes or fiber-optic eyes that check for specific things on every stroke.

- Is the part still stuck in the die? (If the press hits it again, the tool explodes.)

- Did the scrap (the "slug") fail to fall through?

- Is the strip misaligned?

The sensor sends a signal to the press's PLC (Programmable Logic Controller) to stop the machine in milliseconds. This prevents a "smash," which can cost $20,000 in repairs and weeks of lead time. It’s the difference between a minor hiccup and a catastrophic failure.

🔗 Read more: Big Lots in Potsdam NY: What Really Happened to Our Store

Misconceptions That Kill Margins

One of the biggest myths is that "tight tolerances" always mean "better quality."

Actually, over-specifying tolerances can be a sign of bad engineering. If a part functions perfectly with a +/- 0.010 tolerance, but the print calls for +/- 0.001, you are paying for precision you don't need. It forces the toolmaker to use more expensive processes like EDM (Electrical Discharge Machining) and jig grinding, and it makes the stamping process much more prone to generating scrap.

True quality is about functional consistency.

Another misconception is that the cheapest quote is the best value. I’ve seen companies go with a low-ball bid for a stamping tool, only to find out the die was built with "soft" spacers or lacked proper lubrication channels. Within 50,000 cycles, the tool was out of spec. They ended up spending double the original quote just to fix a "cheap" tool.

Inspection: Beyond the Caliper

Quality control (QC) in stamping has moved way beyond a guy with a micrometer.

Vision systems are the gold standard now. As parts come off the press—sometimes at 400 strokes per minute—high-speed cameras take photos of every single one. Software compares these images to the master CAD file in real-time. If a hole is missing or a dimension drifts, the system flags it instantly.

We also use SPC (Statistical Process Control). By measuring a sample of parts every hour, we can see "trends." We might see that a specific dimension is slowly getting larger. That tells us the punch is wearing down. We don't wait for it to produce a bad part; we stop the press and sharpen the tool before the parts go out of spec. That’s proactive quality.

Maintenance is Not Optional

You wouldn't drive a car for 100,000 miles without an oil change. Why do people expect a stamping tool to run a million hits without maintenance?

💡 You might also like: Why 425 Market Street San Francisco California 94105 Stays Relevant in a Remote World

A robust quality tool and stamping program includes "preventative maintenance" (PM) intervals. Every X-thousand hits, the tool comes out of the press. It gets disassembled, cleaned, inspected for micro-cracks, and sharpened. Sharpening involves grinding a few thousandths of an inch off the face of the punch and die to restore a crisp cutting edge. This reduces burr height and keeps the part dimensions stable.

How to Evaluate a Stamping Partner

If you're looking for someone to build your tools and run your parts, don't just look at their press capacity. Ask about their tool room.

- Do they have in-house tool and die makers, or do they outsource it?

- What kind of sensor technology do they use?

- Can they show you their SPC charts for a recent run?

A shop that can't explain their "die protection" strategy isn't a quality shop. Period.

You also want to look at their "first article inspection" (FAI) process. This is the rigorous check of the very first parts off the tool. It should be exhaustive. If they cut corners here, they’ll cut corners when you aren't looking.

Actionable Steps for Better Stamping Results

If you're struggling with part quality right now, here is what you need to do.

First, audit your scrap. Don't just throw it away. Look at it. Are the edges "torn" or "sheared"? A clean shear-to-break ratio (usually 1/3 shear, 2/3 break) indicates the "die clearance"—the gap between the punch and the die—is correct. If it looks like the metal was ripped apart, your clearance is too wide. If there's a double-shear, it's too tight.

Second, review your material certs. Sometimes, the "quality" issue isn't the tool; it's the metal. If the hardness of the incoming coil varies too much, your springback will vary, and your parts will be inconsistent. Insist on material certifications for every lot.

Third, invest in the tool. If you have a high-volume project, pay for the premium tool steel and the coating (like TiN or TicN). It feels like an extra cost upfront, but the "cost per part" over the life of the project will be significantly lower because you'll have less downtime and fewer sharpenings.

Quality isn't a department. It’s a technical requirement of the tooling itself. When the tool is right, the stamping is easy. When the tool is a mess, no amount of inspection will save your reputation. Focus on the steel, the sensors, and the maintenance, and the quality will usually take care of itself.

Next Steps for Implementation:

- Verify Die Clearances: Request a clearance report from your toolmaker for the specific material thickness you are running; standard clearance is typically 10% of material thickness per side, but this varies by alloy.

- Implement Die Protection: Retrofit existing high-value dies with "slug-drop" and "misfeed" sensors to prevent tool damage and catastrophic downtime.

- Analyze Shear-to-Break Ratios: Inspect your part edges under a loop; a consistent 30/70 ratio typically indicates the tool is sharp and clearances are optimal for most mild steels.

- Standardize PM Schedules: Establish a "hits-based" maintenance log for every tool in your inventory to ensure sharpening occurs before burr heights exceed your allowable tolerances.