You probably remember sitting in a stuffy classroom, staring at a chalkboard while a teacher droned on about $a^2 + b^2 = c^2$. It felt like one of those things you'd learn just to pass a test and then promptly delete from your brain the second summer break hit. But here's the thing: the pythagorean theorem of a right triangle is basically the "Swiss Army Knife" of the physical world. It’s not just for architects or guys building bridges. If you’ve ever tried to fit a TV into a corner or wondered if a shortcut across a park was actually faster, you’ve used it. Honestly, it’s everywhere.

The math is simple, yet it holds the universe together in a weirdly specific way. A right triangle has one 90-degree angle. That’s the rule. If you have that, the square of the longest side—the hypotenuse—will always equal the sum of the squares of the other two sides. It sounds rigid. It is rigid. That’s the beauty of it.

The Greek Connection (and Why It Might Be a Lie)

We call it "Pythagorean" because of Pythagoras, a Greek philosopher who lived around 500 BC. He had a cult. No, seriously. The Pythagoreans were a strange bunch who worshipped numbers and thought beans were evil. But history is messy.

👉 See also: Why Dedham Country and Polo Club Stays One of New England's Best Kept Secrets

Archaeologists have found clay tablets from Mesopotamia, specifically the Plimpton 322 tablet, that show the Babylonians knew about these triplets of numbers over a thousand years before Pythagoras was even born. The Indians knew it too; the Baudhayana Sulba Sutra contains a clear statement of the theorem from roughly 800 BC. Pythagoras might have been the one to bring it to the "West" or offer a formal proof, but he definitely didn't "invent" the relationship between the sides of a triangle. He just got the naming rights.

Imagine being a Babylonian builder. You’re trying to make sure a wall is perfectly square. You don't have a laser level. What do you do? You grab a rope. You tie knots at equal intervals so you have lengths of 3, 4, and 5. When you pull that rope into a triangle, that corner is going to be a perfect 90 degrees every single time. It’s practical. It’s ancient. It’s basically the first "life hack" in human history.

Breaking Down the Math Without the Headache

Let’s look at the actual equation: $a^2 + b^2 = c^2$.

The letters $a$ and $b$ are the "legs" of the triangle. They meet at the right angle. The letter $c$ is the hypotenuse. It’s always the longest side. It’s always opposite the right angle.

If $a = 3$ and $b = 4$, then $3 \times 3$ is 9, and $4 \times 4$ is 16. Add them up and you get 25. The square root of 25 is 5. So, $c = 5$. This is what mathematicians call a "Pythagorean Triple." There are infinitely many of these, like 5-12-13 or 8-15-17, but 3-4-5 is the celebrity of the group.

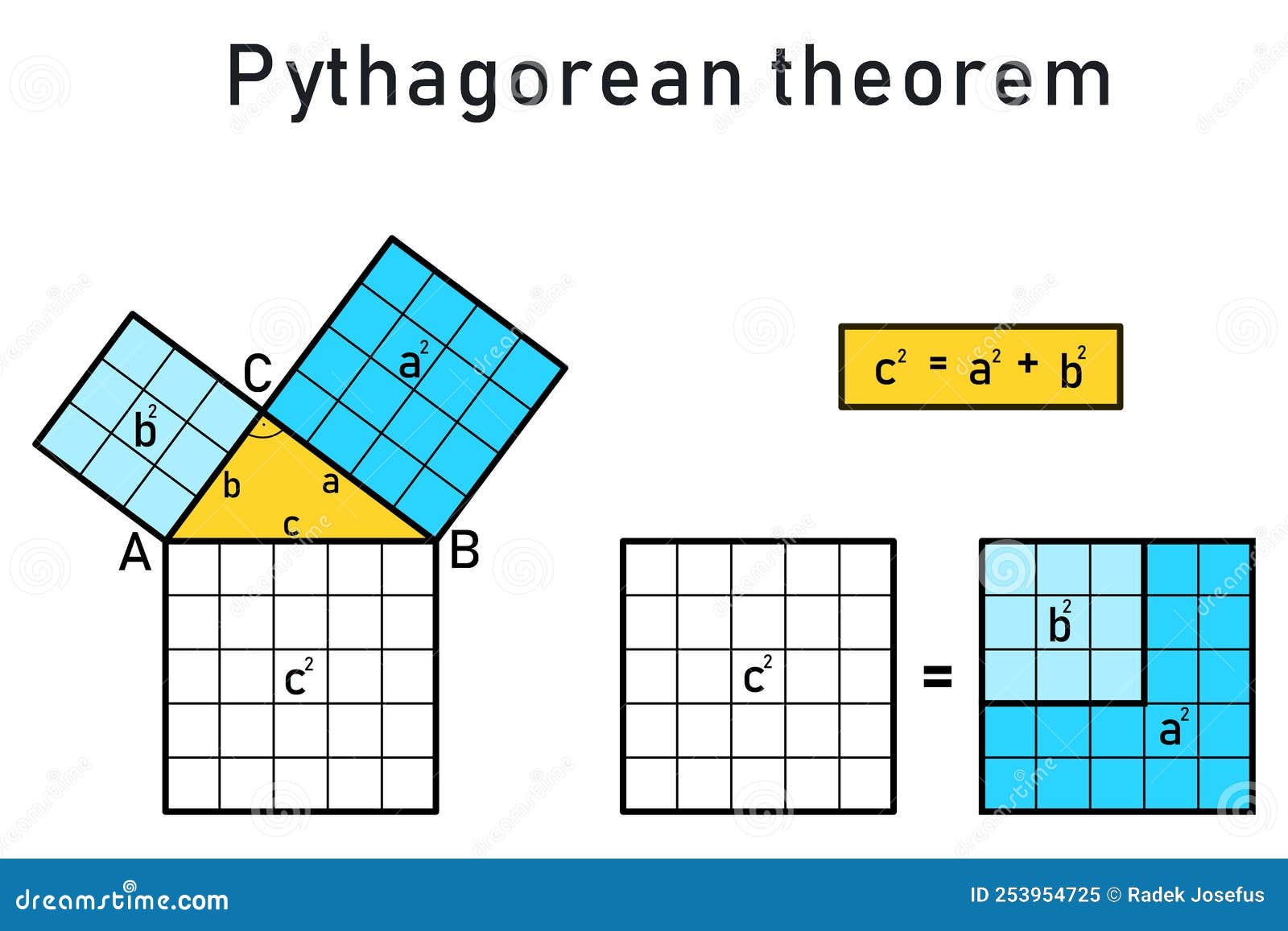

Why the "Square" Matters

When we say $a^2$, we are literally talking about a square. If you drew a physical square off the side of the triangle, its area would be $a$ times $a$. The theorem basically says that if you took two literal squares made of wood and chopped them up, they would fit perfectly into the area of the big square attached to the hypotenuse.

🔗 Read more: Texas Roadhouse in St. George: What Most People Get Wrong

It’s a conservation of space.

Real World: It’s Not Just for Homework

Think about buying a TV. They tell you it's a "65-inch" screen. But if you measure across the bottom, it’s not 65 inches. If you measure the height, it’s definitely not 65 inches. That 65 is the diagonal. It's the hypotenuse.

If you know your TV stand is only 50 inches wide, and the TV is 30 inches tall, you can use the pythagorean theorem of a right triangle to figure out if that "65-inch" screen is going to hang off the edges.

- Navigation: Pilots use it to calculate distance through the air when they know their altitude and their distance from a ground transponder.

- Crime Scenes: Forensic analysts use the theorem to determine the trajectory of a bullet or the "point of origin" for blood spatter. They look at the angles and distances on the floor and walls to reconstruct a 3D triangle.

- Painting a House: If you have a 10-foot ladder and you need to reach a window 8 feet up, how far from the wall should the base of the ladder be? If you put it too close, you tip over backward. Too far, and the ladder slides out. Math keeps you off the ground.

The "Irrational" Freakout

Here is a weird bit of history: the discovery of irrational numbers.

The Pythagoreans believed everything in the universe could be explained by whole numbers or ratios of whole numbers. Then, someone (legend says it was a guy named Hippasus) looked at a right triangle where both legs were 1 unit long.

$1^2 + 1^2 = c^2$

$1 + 1 = 2$

$c = \sqrt{2}$

But the square root of 2 isn't a clean number. It’s $1.41421356...$ and it never ends. It's "irrational."

The story goes that the Pythagoreans were so upset by this—because it broke their worldview that the universe was perfect and orderly—that they took Hippasus out on a boat and drowned him. Whether that's true or just ancient gossip, it shows how much this theorem shook the foundations of how we understand reality. It forced us to accept that math isn't always "tidy."

Common Mistakes People Make

Most people mess this up because they try to use it on triangles that aren't right triangles. If that angle isn't exactly 90 degrees, the formula fails. It just doesn't work. For "slanty" triangles (acute or obtuse), you have to use the Law of Cosines, which is basically the Pythagorean theorem's more complicated, annoying older brother.

Another mistake? Forgetting to take the square root at the end. People do the $a^2 + b^2$ part, get a big number, and think that's the answer. If your triangle legs are 3 and 4, the third side isn't 25. You’ve gotta hit that square root button.

Taking It Into the Third Dimension

The theorem actually scales up. If you want to find the distance between two opposite corners of a room (like from the floor in the front-left to the ceiling in the back-right), you just add another variable: $a^2 + b^2 + d^2 = c^2$.

It's the same logic, just with more depth. This is how GPS works. Your phone isn't just looking at a flat map; it's calculating your position in 3D space relative to satellites orbiting the Earth. Without this specific geometric relationship, your Uber would never find you.

Modern Day Nuance: Is It Always True?

In our daily lives, yes. But if you get into high-level physics or "Non-Euclidean geometry," things get weird.

✨ Don't miss: Black and White Designer Bags: Why the Monochrome Trend Actually Matters in 2026

On a curved surface, like the Earth, the theorem starts to wobble. If you draw a giant triangle on the surface of the globe—say, from the North Pole down to the equator, over a quarter-turn, and back up—the angles actually add up to more than 180 degrees. In that space, $a^2 + b^2$ does not equal $c^2$.

Einstein’s General Relativity tells us that gravity warps space-time. In a heavily warped area of space, like near a black hole, the pythagorean theorem of a right triangle isn't perfectly accurate because the "flat" geometry it relies on doesn't exist there. But for building a deck in your backyard? You're fine.

Practical Steps to Master the Math

If you want to actually use this in your life, don't overthink it. Keep a few things in mind:

- Check for the Square: Before you start calculating, make sure you actually have a right angle. If you're building something, use a carpenter's square.

- The 3-4-5 Rule: This is the easiest way to "square" anything. If you're laying out a garden bed, measure 3 feet one way and 4 feet the other. If the diagonal is exactly 5 feet, your corner is perfect.

- Use an Online Calculator: Look, we live in 2026. You don't need to do square roots by hand. Just search for a "Pythagorean calculator," plug in your two known sides, and let the computer do the heavy lifting.

- Visualize the Squares: If you're teaching this to a kid (or trying to finally understand it yourself), stop thinking about lines. Think about the area. Visualize the actual physical squares sitting on the sides of the triangle.

The theorem is more than just a math problem. It’s a bridge between the abstract world of numbers and the physical world of stuff. It’s one of the few things you learned in middle school that actually stays true no matter where you go in the world—unless you’re falling into a black hole.