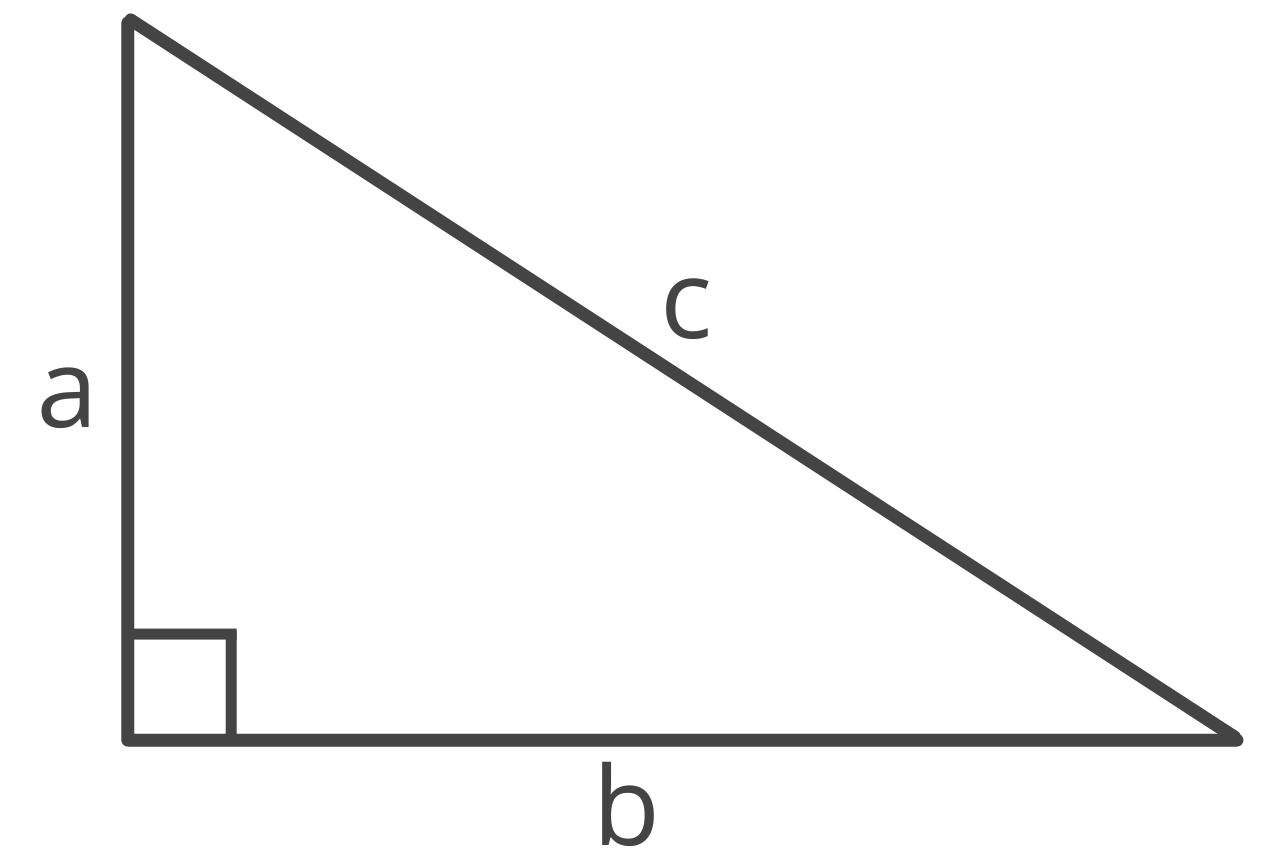

You're staring at a triangle. It’s got a right angle, two sides you know, and a missing angle that’s making your head spin. Naturally, you search for a pythagorean theorem angle calculator because, honestly, who wants to do long-form trigonometry by hand in 2026? But here’s the kicker: the Pythagorean theorem itself doesn't actually find angles. It finds side lengths.

Wait. Don't close the tab yet.

While the formula $a^2 + b^2 = c^2$ is strictly about the relationship between the squares of the sides, every decent online calculator labeled for this purpose is secretly running inverse trigonometric functions under the hood. It’s a bit of a bait-and-switch, but a helpful one. You provide the sides, and the tool uses the ratios to tell you exactly how sharp that corner is. It’s the bridge between geometry and trigonometry that most people stumble over because high school math teachers often keep those two subjects in separate mental boxes.

The Geometry Identity Crisis

We’ve all been there. You remember "A squared plus B squared," but you forget that this specific rule only lives in the world of right triangles. If that corner isn't exactly 90 degrees, the whole thing falls apart like a cheap card table. A pythagorean theorem angle calculator essentially automates the jump from the theorem to the Law of Sines or Cosines.

Think about a carpenter. If they're building a roof pitch, they aren't just worried about the length of the rafters. They need the pitch—the angle. If they use the theorem to find that the rafter needs to be 15 feet, they still need to know at what angle to cut the wood so it sits flush against the ridge board. That’s where the "angle" part of the calculator becomes a lifesaver. It takes the guesswork out of the physical world.

Most of these digital tools use the arctan, arcsin, or arccos functions. If you have the opposite side and the adjacent side, the calculator is doing $\theta = \tan^{-1}(a/b)$. It sounds complicated, but for a computer, it’s a millisecond of work. For a human with a pencil? It’s a recipe for a decimal error that ruins a Saturday afternoon project.

Why We Get This Wrong

There's a common misconception that Pythagoras figured out everything there is to know about triangles. He didn't. He was actually part of a quasi-religious cult that obsessed over integers. To them, irrational numbers—like the ones you get when calculating the angle of a triangle with sides of 1 and 2—were basically heresy. Legend has it they even drowned a guy for proving irrational numbers existed. Dark stuff for a math class.

When you use a pythagorean theorem angle calculator, you're actually using a blend of Greek geometry and much later Arabic and Indian trigonometric advancements. We call it "Pythagorean" because it's a recognizable brand name. It’s like calling every tissue a Kleenex.

Real-World Messiness

Let’s talk about navigation. If you’re a pilot or a sailor, you aren't dealing with perfect triangles on a flat piece of paper. You’re dealing with the curvature of the Earth. However, for short distances, the flat-earth approximation (the Pythagorean approach) works remarkably well.

Imagine you are trying to calculate the drift of a boat. You know you've traveled 10 miles east and 5 miles north. The theorem tells you that you are roughly 11.18 miles from your starting point. But what’s your heading? Your pythagorean theorem angle calculator tells you that you're at a 26.57-degree angle from your original line of travel. Without that angle, the distance is just a number. With the angle, it’s a direction. It’s the difference between being lost at sea and making it home for dinner.

The Math Behind the Screen

I’ve seen plenty of people try to use these calculators without understanding the "Input" requirements. Usually, a tool will ask for:

- Side A (The "rise")

- Side B (The "run")

- Or Side C (The hypotenuse)

If you feed it the wrong side, the angle comes out totally wonky. Most people accidentally swap the "opposite" and "adjacent" sides. In a right triangle, the side opposite the angle you want is... well, the opposite. The one next to it is the adjacent. Simple, right? Yet, it's the number one reason why DIY decks end up looking like Dr. Seuss built them.

The internal logic of a pythagorean theorem angle calculator follows a strict hierarchy. First, it validates that your inputs can actually form a triangle. You can't have a hypotenuse that is shorter than one of the legs. If you try to input that, a well-coded calculator will throw an error. If it doesn't, you're using a bad tool.

📖 Related: Why Photos of the Planet Venus Still Look So Different From What You Expect

Digital Precision vs. Jobsite Reality

There is a nuance to using these tools in 2026 that people overlook: rounding errors. Most calculators will give you an angle to ten decimal places. You don’t need that. No saw on Earth can cut to the 0.00000001 degree. If you’re using a pythagorean theorem angle calculator for a physical project, rounding to the nearest tenth is usually more than enough.

In high-precision fields like aerospace or robotics, those decimals matter. If you're coding a robotic arm to pick up a semiconductor, a tiny deviation in the angle calculation at the "shoulder" joint translates to a massive miss at the "fingertips." This is why modern CAD software integrates these calculations into the very bones of the design process. You don't even see the math; you just move the line, and the software updates the Pythagorean relationship in real-time.

The Evolution of the Tool

Back in the day—and by that, I mean the 1990s—you had to carry a book of sine tables or a bulky Texas Instruments calculator. Now, you have more computing power in your pocket than what sent Apollo 11 to the moon. A pythagorean theorem angle calculator today is often just a small snippet of JavaScript on a website or a specialized app.

Some of the newer ones even use your phone's camera. You point the lens at a physical triangle, the AR (Augmented Reality) overlay identifies the edges, and it spits out the angles. It’s incredibly cool, but it’s still just using the same old Greek math combined with some clever computer vision.

Common Pitfalls to Avoid

- Degrees vs. Radians: This is the big one. Most people think in degrees (0 to 360). Mathematicians often think in radians ($0$ to $2\pi$). If your calculator is set to radians and you're expecting degrees, your 45-degree angle will show up as 0.78. Check your settings.

- The Wrong Corner: Remember, the calculator is usually finding one of the two "sharp" (acute) angles. It assumes you already know the third angle is 90 degrees.

- Inputting the Hypotenuse as a Leg: The hypotenuse ($c$) is always the longest side. If you put the biggest number in the $a$ or $b$ box, the math breaks.

Practical Steps for Accurate Results

If you're about to use a pythagorean theorem angle calculator, don't just blindly trust the first number that pops up. Do a "sanity check" first.

Look at your triangle. Does one angle look much wider than the other? If your calculator says they are both 45 degrees, but your drawing clearly shows one is skinny and one is fat, you've swapped a number somewhere.

- Measure twice. Seriously. If your side lengths are off by even a fraction of an inch, your angle will be wrong.

- Identify the Hypotenuse. Find the side opposite the right angle. That is always $c$.

- Choose your angle. Decide which corner you actually need to know.

- Input carefully. Most tools have three boxes. Fill in the two you know and hit calculate.

- Convert if needed. If you get a decimal and need it in "degrees-minutes-seconds" for navigation, you'll need an extra step.

Using a pythagorean theorem angle calculator is about more than passing a geometry quiz. It's about translating the abstract language of math into the concrete reality of the world around us. Whether you're a student, a woodworker, or just someone trying to figure out if a new sofa will fit through a door at a certain angle, these tools turn a potentially frustrating afternoon into a quick, two-minute task.

Start by identifying your two known sides. Ensure your calculator is set to the correct unit—degrees for most practical uses—and double-check that your hypotenuse is indeed the longest side before you commit to any cuts or designs.