Imagine being a toddler, maybe three years old, and suddenly you’re the center of the known universe. Everyone bows. You aren't allowed to play with other kids. You can’t even go outside your own house—except your house is a 180-acre gilded cage called the Forbidden City. That was the life of Puyi, the man history remembers as the last emperor of China.

He didn't choose it. He was basically a pawn from the moment he was plucked from his family in 1908. While most kids his age were learning to use chopsticks without dropping rice, Puyi was the Xuantong Emperor, the "Son of Heaven," ruling over a massive empire that was, honestly, falling apart at the seams.

The Boy Who Owned the Forbidden City

Puyi’s rise to power was more of a tragedy than a triumph. The formidable Empress Dowager Cixi, while literally on her deathbed, decided this tiny boy would be the one to carry the Qing Dynasty forward. It was a desperate move for a dying regime. He was the nephew of the Guangxu Emperor, and his coronation was a surreal affair. Legend has it the toddler cried throughout the ceremony because it was long, loud, and scary. His father, Prince Chun, supposedly whispered, "It will be over soon," trying to comfort him.

The court officials took those words as a bad omen for the dynasty.

They were right.

For the next few years, Puyi lived a life that sounds like a fever dream. He had thousands of eunuchs at his beck and call. If he wanted a snack, a multi-course meal appeared. If he was naughty, his tutors didn't punish him; they punished a "proxy" child because you couldn't lay a hand on the Emperor. It's a weird way to grow up. You’ve got all the prestige in the world but zero actual agency.

Then came 1912. The Xinhai Revolution changed everything.

📖 Related: Is there actually a legal age to stay home alone? What parents need to know

At just six years old, Puyi was forced to abdicate. China became a Republic. But here is the kicker: he didn't actually leave. The new government let him keep his title and stay in the northern half of the Forbidden City. He was a ghost in his own palace, a relic of an era that the world was moving past at lightning speed.

Why Puyi Still Matters: The Puppet King of Manchukuo

History isn't just about dates; it's about the weird, uncomfortable choices people make when they’re desperate. Puyi spent his teenage years obsessed with getting his power back. He grew up, got married (to Wanrong and Wenxiu), and even started wearing Western clothes and riding a bicycle around the palace—he actually had doorsills sawed off so he could ride through the courtyards.

But the "Republic" wasn't stable. Warlords were fighting, and in 1924, a guy named Feng Yuxiang kicked Puyi out of the Forbidden City for good.

He ended up in Tianjin, under the "protection" of the Japanese. This is where things get controversial. Was Puyi a traitor? Or was he a victim?

In 1932, the Japanese set up a puppet state in Northeast China called Manchukuo. They needed a face for it—someone to give it legitimacy. They tapped Puyi. He was installed as the "Chief Executive" and later the Emperor of Manchukuo. To the rest of the world, he was a collaborator. To Puyi, it was a chance to be a real emperor again.

The reality was bleak. He had no power. The Japanese Kwantung Army called all the shots. He was effectively a prisoner again, just in a different palace. His life during this period was defined by paranoia and a failing marriage. His wife, Empress Wanrong, eventually succumbed to an opium addiction, driven by the isolation and the bizarre pressure of their lives.

👉 See also: The Long Haired Russian Cat Explained: Why the Siberian is Basically a Living Legend

From Emperor to Gardener: The Final Act

The end of World War II was the end of Puyi's royal delusions. When Japan surrendered in 1945, Puyi tried to flee to Japan but was captured by Soviet troops at an airport in Shenyang.

He spent five years in a Siberian prison camp.

Think about that transition. From a golden throne to a Soviet cell.

In 1950, he was handed over to the new People’s Republic of China. Mao Zedong didn't execute him. Instead, Puyi was sent to the Fushun War Criminals Management Centre for "re-education." This is the part of the story that feels like a movie script. The man who once had thousands of servants now had to learn how to tie his own shoelaces. He had to wash his own clothes. He had to write confessions about his "crimes" against the people.

Surprisingly, it worked. Or at least, Puyi played the part perfectly.

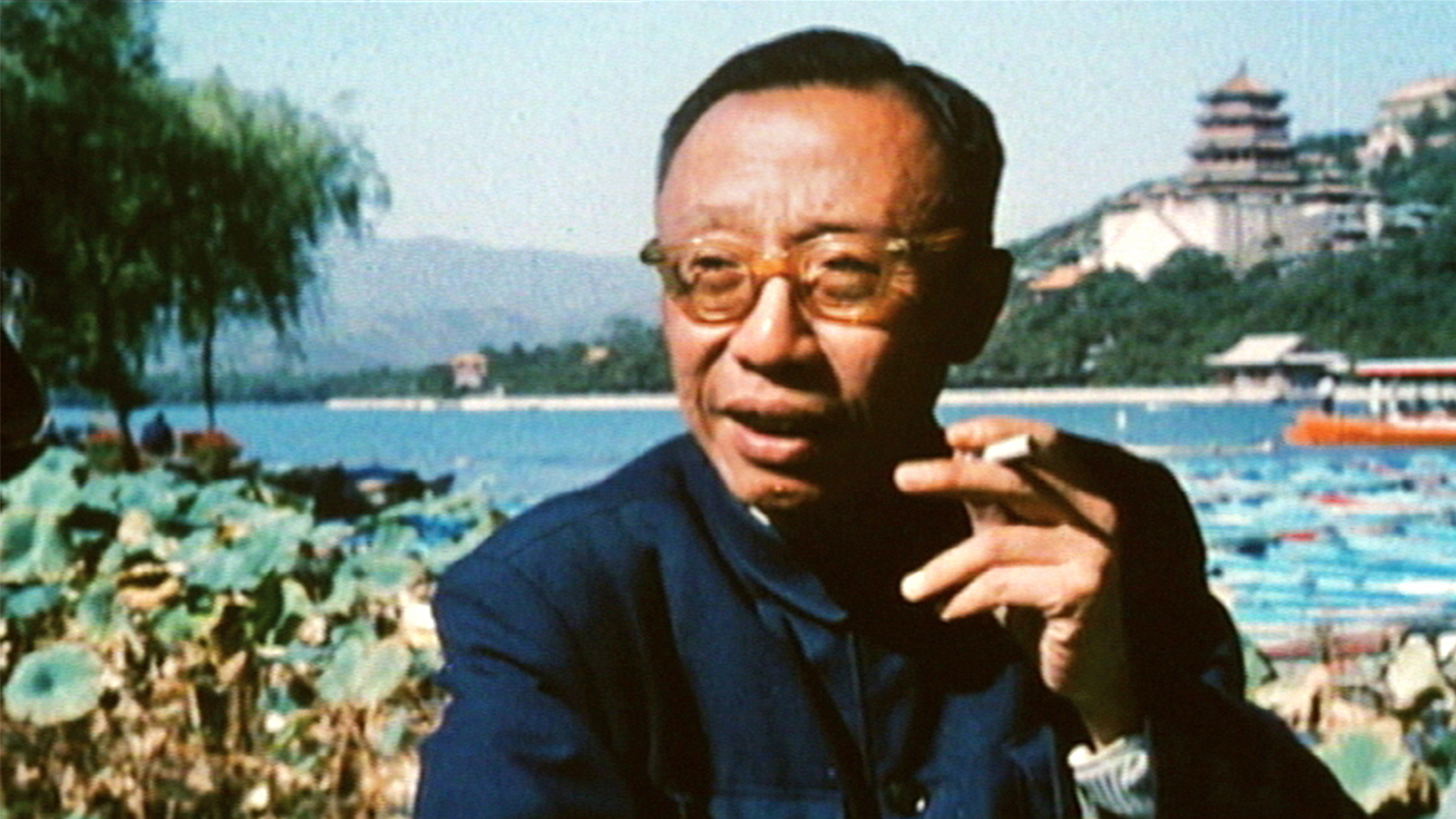

He was released in 1959 via a special pardon. He spent his final years in Beijing working as a simple gardener at the Beijing Botanical Garden and later as a researcher for the National Committee of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference. He even wrote an autobiography, From Emperor to Citizen (or The First Half of My Life), which is a fascinating, if heavily censored, look into his psyche.

✨ Don't miss: Why Every Mom and Daughter Photo You Take Actually Matters

When he died in 1967 from complications related to kidney cancer, he wasn't buried in a massive imperial tomb. He was a regular citizen.

Common Misconceptions About the Last Emperor

People often get a few things wrong when they talk about who was the last emperor of China.

- He wasn't the only "Last Emperor": While Puyi was the last of the Qing Dynasty, Yuan Shikai briefly declared himself emperor in 1915-1916. It lasted about 83 days and was a total disaster. Most historians don't count him because he didn't have the "Mandate of Heaven" or the long-standing dynastic lineage.

- He wasn't a monster: History likes villains, but Puyi was more of a tragic, somewhat pathetic figure. He was a man out of time, constantly used by more powerful people—Cixi, the Japanese, the Soviets, and eventually the Communists.

- The movie The Last Emperor is mostly accurate: Bernardo Bertolucci’s 1987 film is stunning, and while it takes some creative liberties, it captures the loneliness of his life quite well. It was the first film the Chinese government allowed to be shot inside the Forbidden City.

How to Explore This History Today

If you’re interested in the life of Puyi, you can actually trace his footsteps. It’s one of the few historical deep dives where the locations are still mostly intact.

- The Forbidden City (Beijing): Visit the Palace of Earthly Tranquility where he lived. You can see the contrast between the grand halls and the cramped quarters where the "boy emperor" spent his youth.

- The Museum of the Imperial Palace of the Manchu State (Changchun): This was his "palace" during the Manchukuo years. It feels much more like a government building or a prison than a royal residence, which is fitting.

- The Beijing Botanical Garden: You can visit the place where the former Son of Heaven spent his days pruning plants and living a quiet, anonymous life.

Actionable Next Steps for History Buffs

Understanding Puyi requires looking at the primary sources. If you want to go deeper than a Wikipedia summary, start with these steps:

- Read "From Emperor to Citizen": It is Puyi's own account. Keep in mind it was written under the eye of the Communist Party, so he's very hard on his "former self," but the details of palace life are unmatched.

- Research the "Open Door Policy": To understand why the Qing Dynasty fell, you need to understand the foreign pressures China was facing in the early 1900s.

- Compare his life to Nicholas II of Russia: Both were "last" monarchs of massive empires who faced revolution at the same time. The difference in their fates—execution vs. re-education—tells you everything you need to know about the difference between the Russian and Chinese revolutions.

The story of the last emperor is a reminder that no matter how high you are, the tide of history doesn't care about your titles. Puyi started as a god and ended as a gardener. Honestly, he might have been happier with the plants.