Imagine being a three-year-old kid and suddenly, you're the center of the universe. Not just "center of the room" in a cute way, but literally the "Son of Heaven" responsible for the spiritual well-being of millions. That was the reality for Puyi, the last emperor of China, who was plucked from his home in 1908 to rule over a dying dynasty. He didn't ask for it. He probably just wanted to play with his toys. Instead, he got the Forbidden City, a sprawling golden cage where thousands of eunuchs knelt whenever he walked by. It’s a story that feels like a movie—and Bernardo Bertolucci actually made one about him—but the real history is way messier and honestly, kind of heartbreaking.

From God-King to Prisoner: The Paradox of Puyi

When Puyi took the throne, the Qing Dynasty was basically a walking ghost. The empire was broke, foreign powers were carving up Chinese ports like a Thanksgiving turkey, and the people were tired of imperial rule. He was the last emperor of China at a time when China didn't really want an emperor anymore.

Living in the Forbidden City was a surreal existence. He was the absolute master of everything within the walls but had zero power outside them. It’s wild to think that he was still holding court while the Republic of China was being formed right outside the gates. For years, the new government let him keep his title and his staff, creating this weird bubble of 14th-century tradition floating in the middle of a 20th-century revolution. He was a teenager with a high-end camera and a bicycle, riding through ancient courtyards where no one had ever dared to pedal before.

He was lonely. His primary companions were elderly ladies of the court and his tutor, Reginald Johnston. Johnston is a key figure here; he’s the one who gave Puyi a Western perspective, introduced him to spectacles, and basically became his window to the world. Without Johnston, Puyi might have remained a literal museum piece.

The Puppet State of Manchukuo

Things got dark in the 1930s. After being kicked out of the Forbidden City by a warlord in 1924, Puyi ended up in the hands of the Japanese. They saw him as the perfect tool. They wanted to legitimize their occupation of Northeast China (Manchuria), so they offered to make him emperor again.

He jumped at it. It’s easy to judge him for collaborating, but you have to remember he’d been told since birth that he was the rightful ruler of his people. He wanted his throne back. But "Manchukuo" wasn't a real country. It was a Japanese colony with a Chinese face. Puyi quickly realized he was just a prisoner again, this time in a modern palace in Changchun. He couldn't sign a paper or go for a walk without Japanese "advisors" giving him the nod. It was a humiliating second act for the last emperor of China.

📖 Related: The Betta Fish in Vase with Plant Setup: Why Your Fish Is Probably Miserable

During this period, his personal life was a wreck. His wife, Empress Wanrong, descended into a tragic opium addiction. His second wife (or "consort"), Wenxiu, did something absolutely unheard of in imperial history: she divorced him. She literally walked away from an emperor because she couldn't stand the hollow, suffocating life of the court.

The Re-education of a Sovereign

When World War II ended and Japan collapsed, Puyi was captured by the Soviet Union. He reportedly spent his time in a Soviet prison camp gardening and hoping he wouldn't be sent back to China to face Mao Zedong’s communists. But in 1950, he was handed over.

This is where the story gets really interesting from a psychological perspective. Most fallen monarchs end up in exile or at the end of a rope. Puyi was sent to the Fushun War Criminals Management Center. The goal? "Remolding." They wanted to turn the last emperor of China into a model citizen of the People's Republic.

He spent nearly a decade in prison. He learned how to tie his own shoes. He learned how to wash his own clothes. Think about that for a second. This guy had never even poured his own tea for the first thirty years of his life. He was assigned prisoner number 981. There’s a famous account of him being remarkably bad at basic tasks, which makes sense—he’d been treated like a porcelain doll his entire childhood.

Life as a Gardener

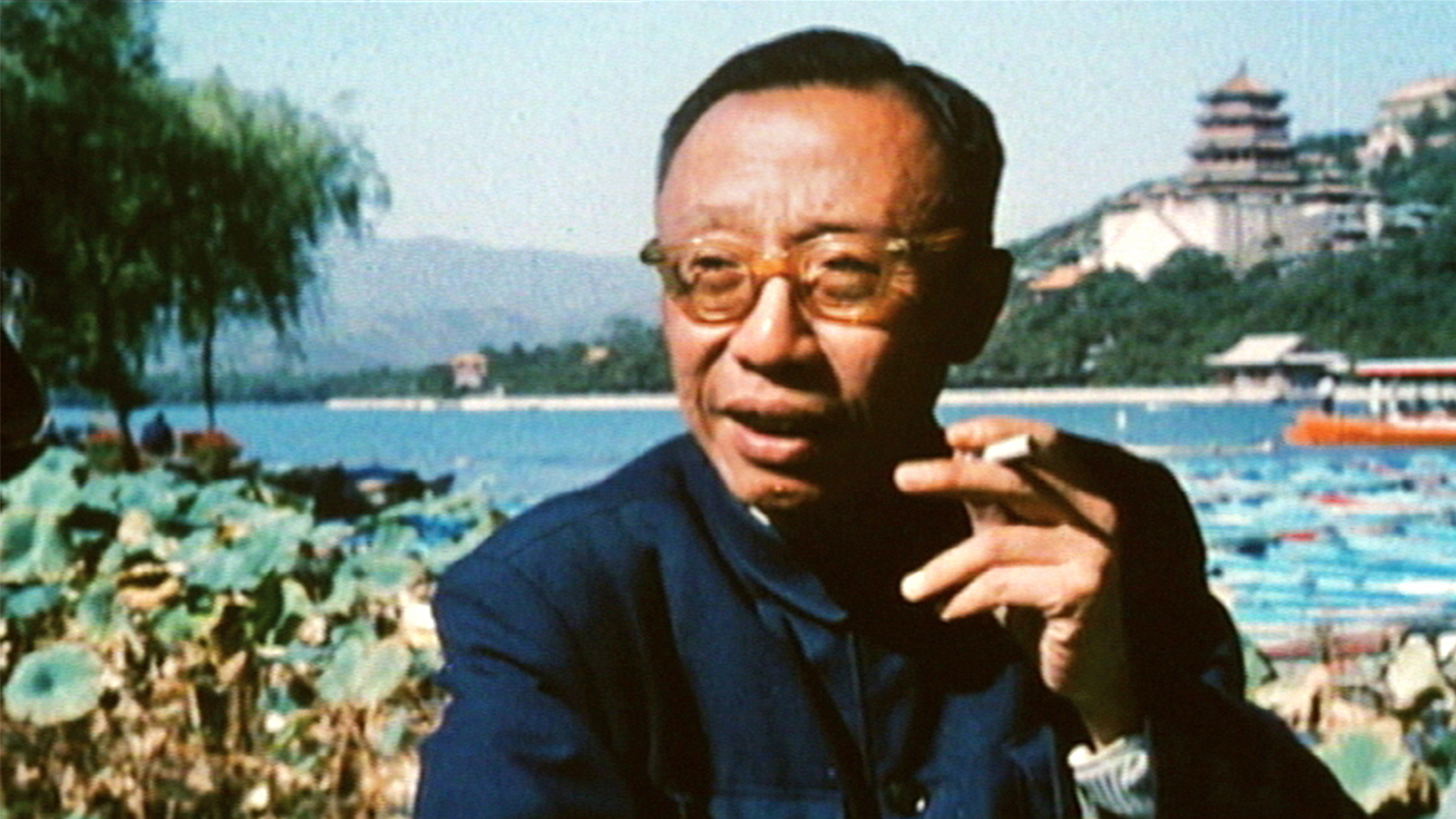

In 1959, he was pardoned. He moved back to Beijing and took a job at the Botanical Gardens. This wasn't a PR stunt; he actually worked. Imagine being a tourist in the 1960s, walking through a park, and the guy pruning the hedges is the former Son of Heaven. He even had to buy a ticket to enter the Forbidden City—his own former home.

👉 See also: Why the Siege of Vienna 1683 Still Echoes in European History Today

He wrote an autobiography called From Emperor to Citizen (or Wo De Qian Ban Sheng). While it was heavily edited by the Communist Party to fit their narrative of "redemption," it still offers a haunting look at a man who lived five different lives in one. He died in 1967, just as the Cultural Revolution was starting to tear China apart. In a way, his timing was lucky; he missed the worst of the chaos that might have seen him targeted again.

What People Get Wrong About the End of the Qing

Most people think the revolution of 1911 was a clean break. It wasn't. The transition from the last emperor of China to a modern state was messy, bloody, and confusing.

- The "Double Tenth" Revolution: It wasn't a single battle but a series of uprisings.

- The Abdication: Puyi’s mother (the Empress Dowager Longyu) signed the papers. Puyi was six. He didn't even know what was happening.

- The Eunuchs: There were about 1,000 eunuchs still in the palace when Puyi was a teen. He eventually kicked them out after they allegedly started fires to cover up their theft of palace treasures.

The nuance here is that Puyi wasn't a villain in the traditional sense. He was a man-child shaped by a system that was already dead before he was born. He was a victim, a collaborator, a prisoner, and finally, a quiet old man.

Lessons from the Last Emperor

If you’re looking for a takeaway from the life of the last emperor of China, it’s about the crushing weight of expectation. Puyi spent his whole life being what other people needed him to be. To the Qing loyalists, he was a symbol. To the Japanese, he was a puppet. To the Communists, he was a trophy of successful re-education.

How to explore this history further:

✨ Don't miss: Why the Blue Jordan 13 Retro Still Dominates the Streets

First, go watch the 1987 film The Last Emperor. It’s visually stunning, though it takes some creative liberties. Then, find a translated copy of his autobiography. It’s fascinating to read his own perspective on how "useless" he felt during his early years.

If you ever visit Beijing, don't just look at the big halls in the Forbidden City. Look at the small, dusty corners in the back. That's where a lonely boy used to play with crickets while the world outside changed forever.

Next Steps for History Buffs:

Check out the memoirs of Lady Hyegyeong or the story of Nicholas II of Russia to compare how different dynasties handled their collapses. Understanding the fall of the Qing is the only way to truly understand why modern China behaves the way it does today. Read up on the "Century of Humiliation"—it’s a term you’ll see everywhere in Chinese politics, and Puyi’s life is the literal embodiment of that era.