It is cold. That’s the first thing everyone says, but "cold" doesn't actually cover it. When you’re standing on the North Slope in the middle of February, the air doesn't just feel chilly; it feels like a physical weight pressing against your chest. We are talking about a place where the sun disappears for weeks at a time, leaving nothing but a purple-blue twilight and the industrial hum of the largest oil field in North America.

Prudhoe Bay isn't a town. Not really. If you go there looking for a Starbucks or a local library, you’re going to be disappointed. It’s a massive, sprawling industrial complex sitting on the edge of the Arctic Ocean. It exists for one reason: oil. Since the discovery of the field in 1968 by Atlantic Richfield (ARCO) and Exxon, this patch of tundra has dictated the economic heartbeat of Alaska.

But things are changing. The "glory days" of the 1980s, when the Trans-Alaska Pipeline System (TAPS) was pumping two million barrels a day, are in the rearview mirror. Today, the conversation is about carbon capture, aging infrastructure, and whether new projects like Willow can keep the lights on in Juneau.

Why Prudhoe Bay Still Matters to Your Wallet

You might live in Florida or New York and think the Arctic is someone else's problem. You'd be wrong. The production levels at Prudhoe Bay and the surrounding North Slope fields directly impact domestic energy security and global oil pricing.

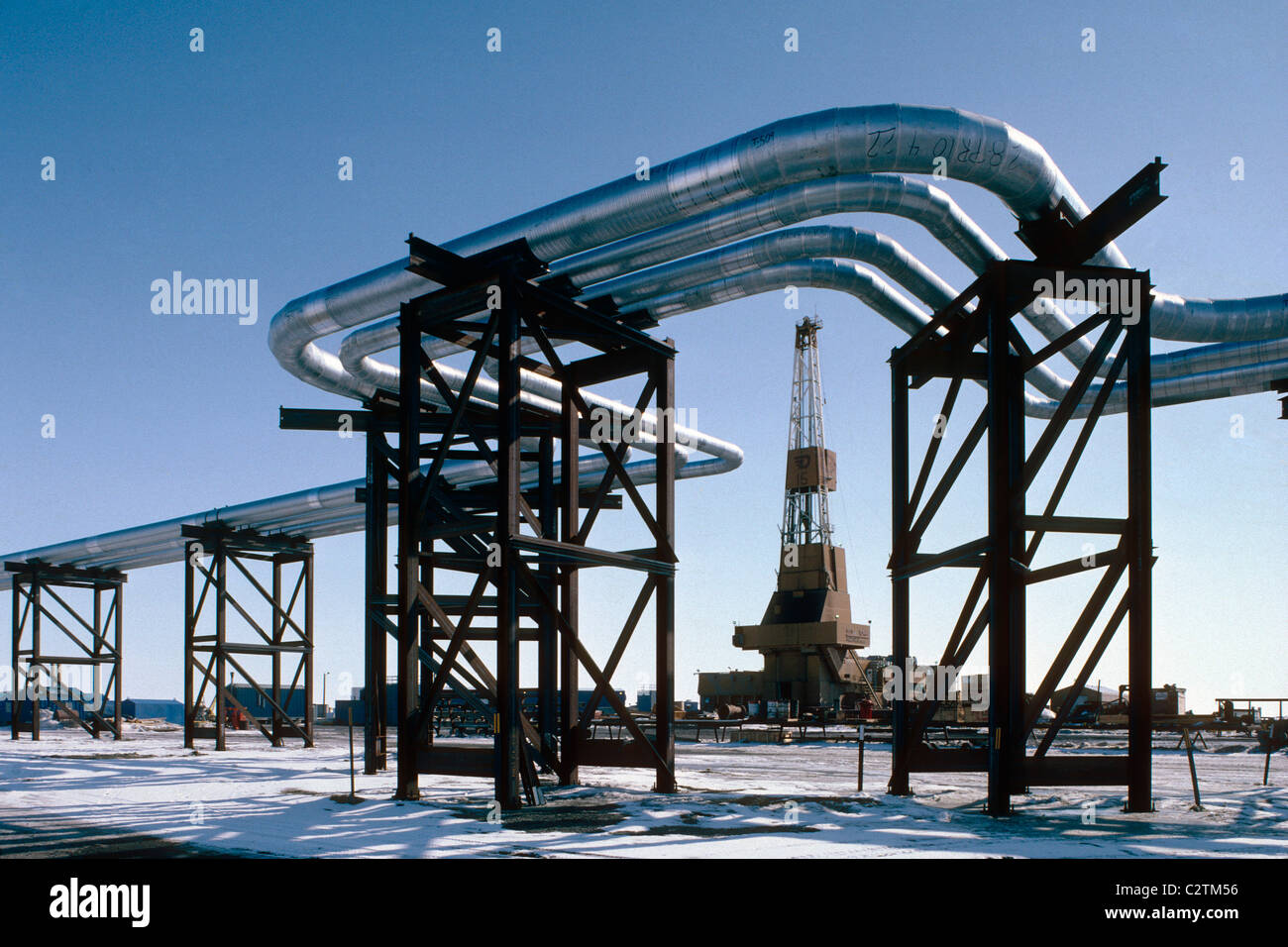

The geology here is staggering. The Prudhoe Bay Oil Pool originally contained over 25 billion barrels of oil. To put that in perspective, that’s enough to fill a medium-sized sea. However, getting it out of the ground isn't as simple as sticking a straw in the earth. The permafrost—the frozen ground that stays frozen year-round—is several hundred feet thick. If you build a warm building or a hot pipe directly on it, the ground turns into a swamp. Everything, from the massive "modules" that house the workers to the drilling rigs themselves, has to be elevated on pilings or placed on thick gravel pads.

✨ Don't miss: Syrian Dinar to Dollar: Why Everyone Gets the Name (and the Rate) Wrong

The Life of a Slope Worker

It’s a weird life. Most people work a "two-and-two" or "three-and-three" schedule. That means you fly into Deadhorse—the service area for Prudhoe Bay—and work twelve hours a day, seven days a week, for two or three weeks straight. Then you fly home to Anchorage or the Lower 48 for your weeks off.

The food is legendary. Because the work is grueling and the environment is hostile, the oil companies (mostly Hilcorp, who took over from BP in a massive 2020 deal, and ConocoPhillips) provide massive buffets. We’re talking prime rib, king crab legs, and every kind of dessert imaginable. It’s a coping mechanism. When it’s -40°F outside and you haven't seen your family in ten days, a good steak matters.

But there’s no booze. None. The North Slope is "dry." If you’re caught with a beer in your room, you’re on the next plane out, and you aren't coming back.

The Environmental Tightrope

Let’s talk about the caribou. You’ll hear two versions of the story. One side says the oil industry has destroyed the Arctic wilderness. The other side points to the Central Arctic Herd, which has actually grown in size since the pipeline was built. The truth is usually somewhere in the middle.

🔗 Read more: New Zealand currency to AUD: Why the exchange rate is shifting in 2026

The industry has gotten much better at "footprint reduction." In the 70s, they built massive gravel pads for every single well. Now, they use directional drilling. A single pad can host dozens of wells that branch out like spider legs for miles underground. This minimizes the impact on the surface.

Still, the permafrost is melting. This isn't a political debate on the North Slope; it’s an engineering nightmare. When the permafrost thaws, roads buckle and building foundations shift. Companies are now using "thermosyphons"—those weird metal tubes sticking out of the ground—to pull heat away from the soil and keep it frozen. It’s a strange irony: using technology to keep the ground frozen so we can extract the fossil fuels that contribute to the ground warming up.

The Willow Project and the Future

If you follow the news, you’ve heard of Willow. Located in the National Petroleum Reserve-Alaska (NPR-A), west of the main Prudhoe Bay hub, this ConocoPhillips project is the next big thing. It’s controversial. Environmental groups sued to stop it, citing the "carbon bomb" effect. Proponents, including many North Slope Iñupiat leaders, argue it’s vital for the local economy and the survival of Arctic communities.

The North Slope Borough relies almost entirely on property taxes from oil infrastructure to fund schools, police, and clinics. Without new projects to replace the declining output of the original fields, those communities face a bleak financial future.

💡 You might also like: How Much Do Chick fil A Operators Make: What Most People Get Wrong

Myths About the Arctic Oil Fields

- Myth 1: It’s an ecological wasteland. Honestly, it’s beautiful. In the summer, the tundra explodes in color. There are millions of migratory birds, muskoxen, and yes, plenty of bears.

- Myth 2: Anyone can just drive up there. Technically, you can drive the Dalton Highway (the "Haul Road"). But you can’t just wander into the oil fields. Security is tight. It’s private property, and you need a reason to be there.

- Myth 3: The oil is running out. There is still plenty of oil. The problem is the cost of extraction. When oil is $40 a barrel, the North Slope struggles. When it’s $90, everyone is hiring.

The technical complexity of what happens at Prudhoe Bay is mind-boggling. They don't just pump oil; they manage a massive water and gas injection system. To keep the pressure up in the reservoir, they reinject massive amounts of produced water and natural gas back into the ground. It’s a giant, closed-loop plumbing system on a planetary scale.

What Most People Miss

People forget that the North Slope is home to people who have lived there for thousands of years. The Iñupiaq people of Utqiagvik (formerly Barrow), Nuiqsut, and Kaktovik are the stakeholders here. They balance a traditional subsistence lifestyle—hunting whales and caribou—with the modern realities of an oil-driven economy.

It's a delicate balance. A spill in the Beaufort Sea wouldn't just be a corporate disaster; it would be a cultural one. That’s why the regulations here are among the strictest in the world.

Actionable Steps for Understanding the North Slope

If you’re interested in the future of energy or the Arctic, don't just read one-sided op-eds. Here is how to actually get a grip on the situation:

- Monitor TAPS Throughput: Check the Alyeska Pipeline Service Company’s website. They publish daily throughput numbers. If that number drops below a certain threshold (around 300,000 to 400,000 barrels), the oil moves too slowly, risks freezing, and the whole system faces "low flow" technical challenges.

- Follow the Alaska Department of Natural Resources (DNR): They release annual "Fall Lease Sale" reports. These tell you exactly where companies are betting their money. If you see high bids in the Beaufort Sea or the NPR-A, you know the industry is bullish.

- Research Carbon Capture Projects: The next phase of Prudhoe Bay isn't just oil; it's sequestration. Look into how Hilcorp and others are exploring using old reservoirs to store $CO_2$. This could be the key to keeping the North Slope relevant in a net-zero world.

- Look at the Arctic Council Reports: For a non-partisan view of how the environment is actually changing, the Arctic Council’s working groups provide the best data on sea ice, permafrost, and biodiversity.

The North Slope and Prudhoe Bay are at a crossroads. We are seeing a transition from a wild-west oil frontier to a highly managed, technologically advanced energy hub. Whether it remains the "Golden Goose" of Alaska for another fifty years depends on a mix of global oil prices, federal policy, and the sheer engineering will to keep operating in one of the most unforgiving places on Earth.

For anyone looking to work there or invest in the region, the days of easy oil are gone. Everything now is about efficiency, carbon intensity, and social license. It’s a tough business. But then again, nothing about the North Slope was ever supposed to be easy.