You’re walking down the street and find a $100 bill. You’re stoked. It’s a free dinner, a new pair of shoes, or just a nice ego boost. Now, imagine a different scenario: you walk down that same street, and a $100 bill falls out of your pocket. You lose it forever.

Statistically, the net change in your life is the same in both scenarios. It’s just a hundred bucks. But emotionally? Losing that money hurts way more than finding it feels good. That’s not just you being dramatic. It’s a fundamental quirk of human psychology called prospect theory.

Most of us like to think we’re rational. We believe we weigh options like a computer, calculating probabilities to maximize our gain. We don't. In 1979, two psychologists named Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky basically nuked the idea of the "rational economic actor." They realized that people don't actually care about the absolute outcome of a decision. We care about the change from our current status quo.

What Is Prospect Theory and Why Should You Care?

Basically, it’s a model that describes how people choose between probabilistic alternatives where risk is involved. Before Kahneman and Tversky, the reigning king was Expected Utility Theory. That old-school model suggested that if you had a 50% chance of winning $1,000, you’d value that "prospect" at $500. Simple math.

But real life is messier.

Prospect theory proved that we are "loss averse." We’re hardwired to avoid losses more than we’re motivated to achieve gains. Some studies suggest the pain of losing is twice as powerful as the joy of winning. This isn't just a fun trivia fact for your next dinner party; it's the reason why people hold onto tanking stocks for too long and why marketing "limited time offers" works so well.

The Reference Point Matters

Everything in your brain is relative. If you make $60,000 a year and get a $5,000 bonus, you’re on cloud nine. If your coworker makes $100,000 and gets the same $5,000 bonus, they might feel insulted. The money is identical. The reference point—where you started—is what changed the value.

Kahneman and Tversky noticed that we evaluate things based on a "neutral" starting position. If you’re used to driving a junker, a 2018 Honda Civic feels like a Bentley. If you’re used to Ferraris, that Civic feels like a golf cart. This sounds obvious, but it completely broke the way economists thought about wealth. They used to think $1,000 was just $1,000 regardless of who had it. Prospect theory says nope.

💡 You might also like: Where is the Toyota Tacoma Made? What Most People Get Wrong

The Famous "Certainty Effect"

People love a sure thing. It’s a weird obsession.

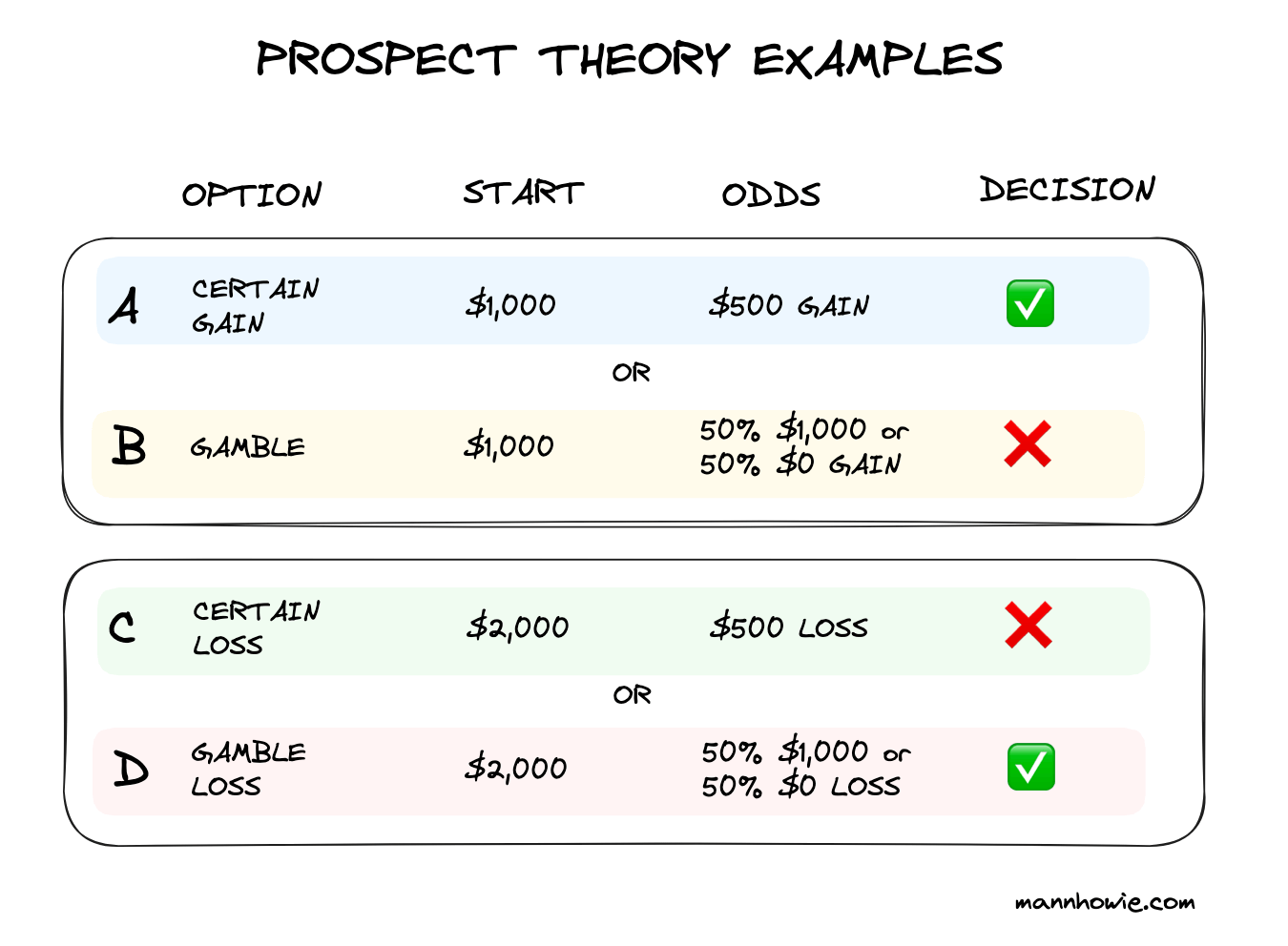

In one of their most famous experiments, Kahneman and Tversky gave participants two choices.

Choice A: A guaranteed $3,000.

Choice B: An 80% chance to win $4,000 and a 20% chance to win nothing.

Math-wise, Choice B is "worth" more ($3,200). But almost everyone picks Choice A. We overvalue certainty. We’ll take the bird in the hand even if there are three birds in the bush.

However, flip the script to losses, and we become total gamblers.

Choice A: A guaranteed loss of $3,000.

Choice B: An 80% chance to lose $4,000 and a 20% chance to lose nothing.

In this case, most people suddenly become risk-takers. They’ll gamble on that 20% chance of losing nothing, even though the "expected loss" of Choice B ($3,200) is higher than the certain loss. We hate losing so much that we’ll take massive, stupid risks just for a tiny sliver of hope that we can break even.

The Fourfold Pattern of Risk

This leads to what's often called the fourfold pattern of risk preferences. It’s kinda the "Grand Unified Theory" of why we make weird bets.

- High Probability Gains: We are risk-averse. We take the "sure thing" even if it's less than the average expected win. (Fear of disappointment).

- High Probability Losses: We are risk-seeking. We gamble to avoid a certain loss. (Desperation).

- Low Probability Gains: We are risk-seeking. This is why people buy lottery tickets. A 0.0001% chance at a million bucks feels better than the $2 in your pocket.

- Low Probability Losses: We are risk-averse. This is why we buy insurance. We pay a "certain" small loss (premium) to avoid a tiny chance of a massive catastrophe.

Real-World Consequences of Loss Aversion

Marketing departments have been using this against you for decades. Ever seen a "subscription discount" that says "Save $50" versus "Don't lose $50"? The latter usually converts better. We’re terrified of leaving money on the table.

In the stock market, this is called the Disposition Effect. Investors tend to sell their "winners" (stocks that have gone up) too early to lock in the feeling of a gain. Meanwhile, they hold onto "losers" (stocks that are crashing) for way too long, hoping they’ll "get back to even." They’re gambling on the 20% chance of a recovery because they can't stomach the "certain loss" of clicking the sell button.

👉 See also: US dollar exchange rate in Mexico: Why the Peso is Defying the Odds in 2026

It also shows up in professional sports. A study of PGA golfers found they were much more accurate when putting for par (avoiding a "loss" of a stroke) than when putting for a birdie (making a "gain"). The pressure of the loss sharpened their focus in a way the potential for a gain didn't.

Why Does Our Brain Do This?

Evolutionarily, it makes sense. If you’re a hunter-gatherer, finding an extra bush of berries is nice—it helps you thrive. But losing your current supply of berries means you starve. In the wild, "avoiding death" is a much higher priority than "getting slightly more comfortable." Our brains are still running on that 50,000-year-old software, even when we’re just looking at a Robinhood app.

The Math Behind the Emotion

Kahneman and Tversky didn't just write a bunch of observations; they created a mathematical "Value Function."

$$v(x) = \begin{cases} x^\alpha & x \geq 0 \ -\lambda(-x)^\beta & x < 0 \end{cases}$$

In this formula, $x$ is the change from the reference point. The $\lambda$ (lambda) represents the loss aversion coefficient. For most people, that number is between 1.5 and 2.5. This means a loss of $x$ hurts about twice as much as a gain of $x$ feels good.

The graph of this function isn't a straight line. It’s an S-curve. It's steep near the reference point and flattens out as you get further away. If you win $10, you're happy. If you win $100, you're happier. But the jump from $10,000 to $10,100 barely registers. This is "diminishing sensitivity."

Common Misconceptions About Prospect Theory

A lot of people think prospect theory says humans are just "dumb" or "irrational." That’s not quite it. It’s that our rationality is bounded. We have limited processing power and we use heuristics—mental shortcuts—to navigate a complex world.

Another mistake is thinking that everyone has the same reference point. Wealthy people have a different "neutral" than people living paycheck to paycheck. If you have $10 million in the bank, losing $1,000 doesn't trigger the "loss aversion" response because it doesn't threaten your status quo. For someone with $1,000 total, losing it is a catastrophe.

How to Beat Your Own Brain

Since you know your brain is biased, you can actually set up "guardrails" to stop yourself from making bad choices.

First, reframe your losses. Instead of looking at a stock that dropped 10% and thinking "I've lost $500," ask yourself: "If I had $4,500 cash today, would I buy this stock at this price?" If the answer is no, sell it. The $500 is gone regardless of whether you sell or hold.

Second, check your reference points. We often get miserable because we compare ourselves to people doing better. If you got a 5% raise, but your friend got 10%, your "reference point" shifts and you feel like you lost money. Stop that. Compare yourself to your own past performance, not someone else's highlight reel.

Third, wait 24 hours. High-stakes decisions often trigger the "fight or flight" response associated with loss aversion. When you're in that state, you're more likely to take a "desperate gamble" to avoid a loss. Sleeping on it allows your prefrontal cortex—the logical part of your brain—to take back the steering wheel.

💡 You might also like: CT Garvin Huntsville Closing: What Really Happened to This 91-Year-Old Landmark

Actionable Insights for Daily Life

- For Business Owners: Structure your pricing as "discounts for early payment" rather than "penalties for late payment." People hate penalties (losses) more than they love discounts.

- For Investors: Set "stop-loss" orders automatically. Take the emotion out of the "sell" decision so you don't fall into the trap of gambling on a dying company.

- For Negotiators: Frame your offer in terms of what the other person stands to lose if they don't take the deal. "You're losing $200 a day in efficiency" is often more persuasive than "You'll save $200 a day."

- For Personal Happiness: Practice "negative visualization." Spend a minute imagining what it would be like to lose something you have (your car, your health, your home). When you return to your "reference point," you’ll feel a surge of "gain" without actually spending a dime.

Kahneman eventually won a Nobel Prize for this work. Tversky likely would have shared it if he hadn't passed away before it was awarded. Their legacy isn't just a bunch of graphs; it's a mirror. It shows us that we aren't the logic-driven machines we pretend to be. We are emotional, loss-fearing, status-quo-clinging creatures—and once you accept that, you can finally start making better decisions.

Next Steps for You

- Audit your subscriptions: Identify "sunk costs" where you’re paying for something just because you don't want to "lose" the access, even if you don't use it.

- Re-evaluate your portfolio: Look at your biggest "loser" and ask if you'd buy it today at its current price. If not, sell it.

- Change your language: Next time you’re trying to persuade someone, focus on what they will miss out on rather than just the benefits they’ll gain.