You’re basically a walking construction site. Every single second, millions of your cells are splitting apart to make new ones. It’s a chaotic, high-stakes dance, and honestly, if it trips up even a little bit, things go south fast. Most of us learned about this in ninth-grade biology, but the textbooks usually make it sound like a boring, static list of phases. They focus on the "what" and totally skip over the "how." The truth? The prophase of mitosis is the most dramatic part of the whole process. It’s the moment the cell decides to stop being one thing and starts the violent, mechanical process of becoming two.

It isn't just a "preparation step." It’s a total cellular overhaul.

Think about it. Inside that tiny nucleus, you have six feet of DNA shoved into a space smaller than a grain of dust. If you tried to pull that apart while it was still all tangled and loose, it would snap. You’d end up with broken genetic code, which is basically a recipe for cancer or cell death. To prevent that, the cell spends prophase packing its bags with extreme precision.

The Great Condensation: DNA Goes Into Lockdown

In a resting cell (interphase), your DNA looks like a bowl of wet spaghetti. Scientists call this chromatin. It’s loose and messy because the cell needs to be able to "read" the genes to make proteins. But once the prophase of mitosis kicks off, that accessibility is over.

The DNA starts coiling. And coiling. And coiling.

This is where those iconic X-shaped chromosomes finally appear. They aren't always there! They only show up during division. A protein complex called condensin acts like a microscopic zip-tie, looping the DNA fibers tighter and tighter until they are chunky enough to move without breaking. It’s a massive structural shift. Imagine trying to move a whole house's worth of loose yarn versus moving neatly packed crates. That’s what your cell is doing.

Each chromosome consists of two identical "sister chromatids." They are joined at a "waist" called the centromere. It’s a weirdly strong bond. They have to stay together for now because the cell needs to make sure each new daughter cell gets exactly one copy. If they drift apart too early, the math won't add up later.

👉 See also: What Does DM Mean in a Cough Syrup: The Truth About Dextromethorphan

Melting the Nucleus

While the DNA is packing, something even crazier is happening. The nucleus—the "brain" of the cell—literally starts to disappear.

For the chromosomes to move to opposite sides of the cell, the nuclear envelope has to get out of the way. It doesn't just "dissolve" into nothingness, though. It actually breaks down into tiny little bubbles called vesicles. These vesicles hang out in the cytoplasm, waiting for the end of mitosis so they can be recycled to build a new nucleus later.

At the same time, the nucleolus—that dark spot inside the nucleus where ribosomes are made—just vanishes. It’s like the cell is shutting down all non-essential business. No more protein production. No more reading instructions. All energy is diverted to the split.

The Construction of the Spindle

Outside the nucleus, two little organelles called centrosomes start moving away from each other. Think of them as the poles of the cell. As they move, they trail long, thin fibers called microtubules behind them. This is the mitotic spindle.

This spindle is the cell's mechanical engine. It’s made of the same stuff as your skeleton (on a cellular level), and its job is to reach out, grab the chromosomes, and pull. Without a perfectly formed spindle during the prophase of mitosis, the chromosomes would just float around aimlessly.

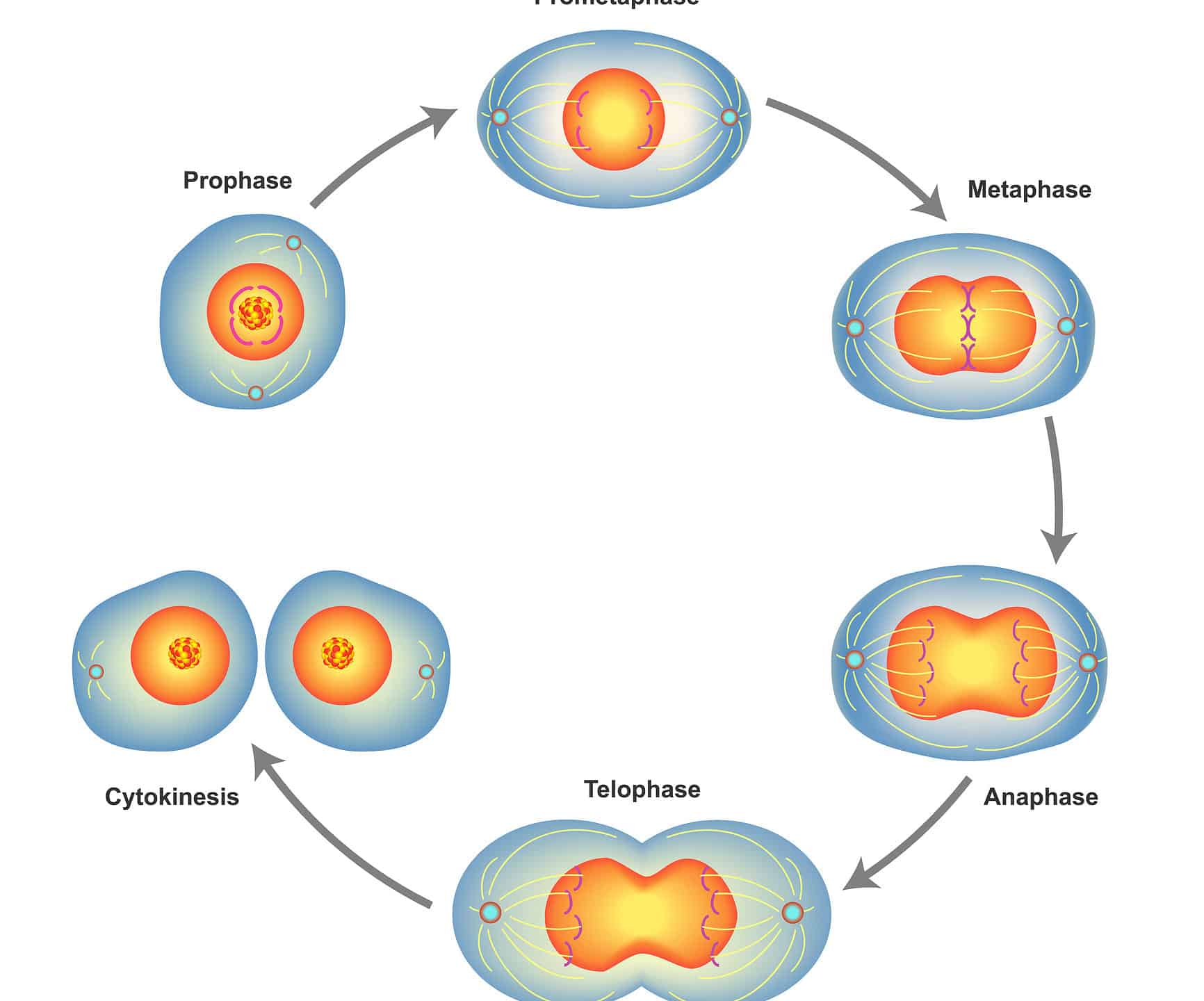

Sometimes people get confused between "early" and "late" prophase (the latter often called prometaphase). In the early stages, the spindle is just starting to grow. By the end, the nuclear wall is gone, and those spindle fibers are desperately searching for a place to hook onto the chromosomes.

✨ Don't miss: Creatine Explained: What Most People Get Wrong About the World's Most Popular Supplement

The Kinetochore: The "Hook" You Never Heard About

This is where the real nuance comes in. On each side of the chromosome's centromere, a specialized protein structure called the kinetochore forms.

It’s basically a biological trailer hitch.

The spindle fibers aren't just bumping into the chromosomes by accident. They are looking for that kinetochore. Once they "catch" it, they lock on tight. This creates a "tug-of-war" tension. If the fiber from the North Pole of the cell grabs the chromosome, a fiber from the South Pole needs to grab the other side. This tension is how the cell knows everything is lined up correctly. If the cell doesn't feel that tension, it actually triggers a "checkpoint" that pauses the whole process.

Why This Matters for Your Health

This isn't just academic trivia. Many of the most effective chemotherapy drugs used today, like Paclitaxel (Taxol) or Vincristine, work by messing with exactly what happens during prophase and its transition to metaphase.

Taxol, for instance, freezes the microtubule spindle. It prevents the fibers from breaking down or moving correctly. When a cancer cell tries to divide and hits prophase, it gets stuck. It can't complete the move, the "checkpoint" realizes something is wrong, and the cell eventually undergoes apoptosis—basically cellular suicide.

When you look at it that way, prophase is the frontline of cancer treatment.

🔗 Read more: Blackhead Removal Tools: What You’re Probably Doing Wrong and How to Fix It

Misconceptions About the Start of Mitosis

A lot of people think prophase is the longest stage of the cell cycle. It's not. That’s interphase (where the cell spends about 90% of its life). But prophase is usually the longest phase of mitosis itself. There's just so much mechanical work to do.

Another common mistake? Thinking that the DNA is replicated during prophase.

Nope.

The DNA was already copied during the S-phase of interphase. Prophase is just about organizing the copies. If you don't have two copies by the time prophase starts, the cell has already failed.

How to Visualize the Process

If you're trying to wrap your head around this for a lab or an exam, stop trying to memorize the text. Look at the structures.

- Chromosomes: Look like fat worms or Xs.

- Centrosomes: The "anchors" moving to the sides.

- Nuclear Envelope: A dashed or disappearing circle.

If you see a cell where the nucleus looks "grainy" or "streaky" under a microscope, you're likely looking at early prophase. The DNA is just starting to clump. If you see distinct X-shapes but they're all clustered in the center area without a border around them, that's late prophase.

Actionable Insights for Biology Students and Professionals

To truly master the mechanics of the prophase of mitosis, don't just read about it—interact with the concepts.

- Use Fluorescence Microscopy Images: Search for "DAPI staining prophase." You'll see the DNA in glowing blue. It helps you see the "messy" vs "organized" transition much better than a cartoon diagram.

- Study the Checkpoints: Look into the Spindle Assembly Checkpoint (SAC). Understanding why the cell stops if prophase goes wrong is the best way to understand why the phase is so important.

- Draw the Transition: Draw a cell with a solid nucleus. Then draw it with a dashed line nucleus. Then draw it with no nucleus but with a spindle. Being able to sketch the breakdown of the nuclear envelope is the "A-ha!" moment for most students.

- Connect it to Pathology: If you're into medicine, read up on aneuploidy. This is what happens when prophase or the subsequent stages fail, leading to cells with the wrong number of chromosomes (like in Down Syndrome or many types of tumors).

Prophase is the setup for the entire future of that cell line. It’s the moment of no return. Once those chromosomes condense and that nucleus breaks, the cell is committed to the split. It’s a masterpiece of biological engineering that happens trillions of times in your body every single day.