It’s kind of wild to think that one of the most beloved staples of the violin repertoire wasn't even written for the violin. Not originally, anyway. If you’ve ever sat in a concert hall and felt that breezy, neoclassical charm of the Prokofiev Violin Sonata 2, you were actually listening to a repurposed flute piece. Sergei Prokofiev was a bit of a pragmatist. He had this Flute Sonata in D Major, Op. 94, sitting around in 1943, and his friend—the legendary violinist David Oistrakh—basically nagged him into converting it. Oistrakh heard the flute version and immediately saw the potential for the bow. He realized the soaring melodies and rhythmic "bite" would translate perfectly to four strings.

The transition happened in 1944. It wasn't just a copy-paste job. Prokofiev, with Oistrakh’s technical input, had to rethink how the articulation worked. A flutist breathes; a violinist uses a bow. That change in physics changes the soul of the music.

Why the Prokofiev Violin Sonata 2 sounds so different from his other work

If you compare this to his First Violin Sonata (Op. 80), it's like looking at two different composers. The First is dark. It’s brooding, graveyard-shadow music. Prokofiev himself described parts of it as "wind passing through a graveyard." But the Prokofiev Violin Sonata 2? It’s sunshine. It was composed while he was evacuated to the Ural Mountains and later Perm during World War II, yet it feels remarkably unburdened by the conflict. While the Soviet Union was locked in a brutal struggle, Prokofiev was looking back toward the clarity of the 18th century, mixing it with his signature "wrong note" modernism.

It’s neoclassical but with a smirk.

You get these soaring, lyrical themes that feel almost Mozart-ian, and then—bam—a sudden harmonic shift that reminds you you're in the 20th century. This duality is why audiences love it. It’s accessible but never boring. It’s technically demanding for the performer but feels effortless to the listener. That’s a hard balance to strike. Most composers either make it sound hard or make it sound simple. Prokofiev makes it sound like a sophisticated joke that everyone is in on.

Breaking down the movements without the jargon

The first movement (Moderato) starts with a theme so graceful you’d swear it was written for a singer. It’s expansive. The violin climbs into the high register, shimmering over the piano’s rhythmic pulse. Honestly, the piano part here is just as important as the violin. It’s not just an accompaniment; it’s a partner in a very witty conversation.

Then comes the Scherzo. This is where the flute origins are most obvious. It’s jumpy. It’s caffeinated. There are these rapid-fire scales and percussive leaps that require a violinist to have a rock-solid left hand and a very bouncy bow arm. Prokofiev throws in these folk-like trios that feel like a brief trip to a village fair before sprinting back into the chaos.

🔗 Read more: Jack Blocker American Idol Journey: What Most People Get Wrong

The third movement (Andante) is the heart of the piece. It’s sentimental without being cheesy. In the original flute version, this movement is all about breath control. On the violin, it’s about the vibrato and the "ring" of the instrument. It’s incredibly brief—only about three or four minutes—but it stays with you.

Finally, the Allegro con brio. This is the closer. It’s big, heroic, and unapologetically loud in places. It has this stomping, rhythmic drive that feels like a celebration. When Oistrakh premiered this in Moscow on June 17, 1944, with Lev Oborin at the piano, it was an instant hit. You can hear why. It’s a "feel-good" piece that doesn't sacrifice intellectual depth.

The Oistrakh Factor: How a performer shaped the notes

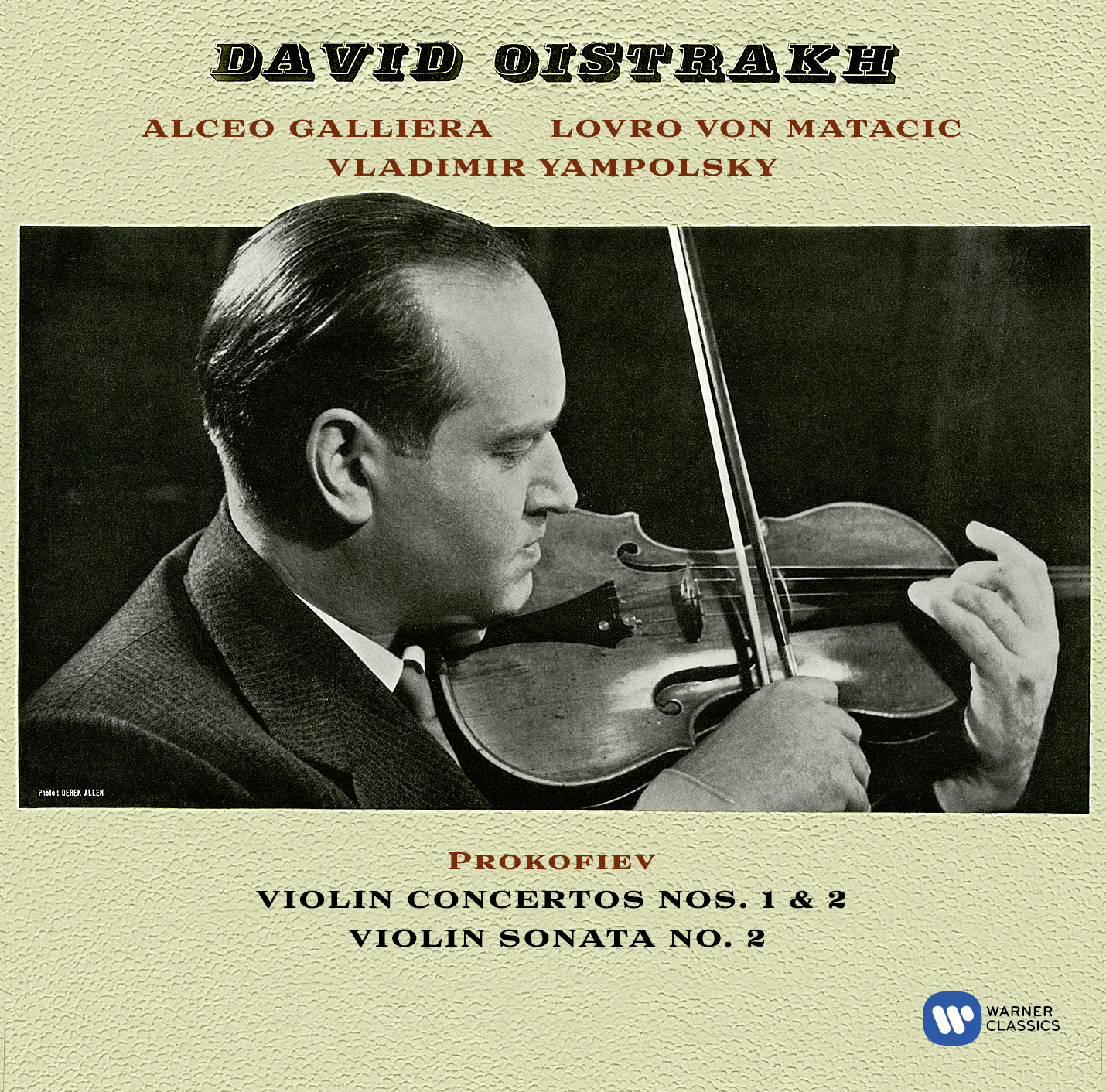

We can’t talk about the Prokofiev Violin Sonata 2 without giving credit to David Oistrakh. He didn't just ask for the transcription; he basically co-edited it. Oistrakh suggested specific fingerings and bowings that made the flute’s agile leaps work for the violin’s fingerboard. This collaboration is why the piece feels so "violinistic" despite its origins.

Oistrakh was the "King David" of the Soviet violin school. His tone was massive, warm, and chocolatey. When he played this sonata, he brought a sense of muscularity to the lyricism. If you listen to his recordings from the 1950s, you hear a version of Prokofiev that isn't just "spiky" or "mechanical." It’s human.

There’s a common misconception that Prokofiev was a cold, mathematical composer. People point to his "Scythian" period or his percussive piano concertos as proof. But the Second Violin Sonata proves the opposite. It shows he was a master of melody. He knew how to write a "hook" just as well as any pop songwriter today, he just dressed it up in complex counterpoint and bitonal harmonies.

The debate: Flute or Violin?

Purists often argue about which version is superior. Flutists will tell you the original Op. 94 has a lightness and a "silver" quality that the violin can't match. They’ll point to the way the air moves through the instrument in the third movement.

💡 You might also like: Why American Beauty by the Grateful Dead is Still the Gold Standard of Americana

Violinists, obviously, disagree. They argue the violin adds a layer of grit and dynamic range that the flute lacks. The violin can growl in the lower register and scream in the upper. It can play double stops (two notes at once), which Prokofiev added for the violin version to fill out the texture.

Honestly? Both are great. But the violin version has undeniably become the more famous of the two. It’s performed more often in major recitals, and it’s a required piece for many international competitions. It’s become a benchmark for a violinist’s ability to handle "lyrical modernism."

Technical hurdles for the modern player

If you’re a violinist looking to tackle the Prokofiev Violin Sonata 2, you’ve got your work cut out for you. It looks easier on the page than it feels in the hands. The biggest challenge isn't the fast notes—it's the intonation. Prokofiev loves to shift keys when you least expect it. You’ll be cruising along in D Major, and suddenly he drops a flattened second or a sharp fourth that feels completely alien. If you don't have a "true" ear, those notes just sound like mistakes.

Then there’s the rhythm. Prokofiev’s music has a motoric quality. It needs to drive forward like a machine, but it can’t sound stiff. You need to find the "groove" in the Scherzo without letting it turn into a technical exercise.

- Work on the "Prokofiev Sound": This means a bow stroke that is crisp and percussive but capable of sudden, lush warmth.

- Focus on the piano cues: You cannot play this piece in a vacuum. The piano sets the harmonic "vibe." If you aren't listening to the left hand of the piano, your intonation will suffer.

- Don't over-sentimentalize: It’s tempting to play the Andante like Tchaikovsky. Don't. Prokofiev needs a bit of distance. It’s cool, detached beauty, not heart-on-sleeve romanticism.

Where to start your listening journey

If you want to understand this piece, you need to hear a few different interpretations. Start with Oistrakh, obviously. He’s the source code. His 1955 recording with Vladimir Yampolsky is the gold standard.

Next, check out Itzhak Perlman. He brings a sweetness to the melodies that really highlights the "flute-like" origins of the work. For something more modern and perhaps a bit more "edgy," listen to Viktoria Mullova. She captures that Soviet "steel" that lies just beneath the surface of the pretty tunes.

📖 Related: Why October London Make Me Wanna Is the Soul Revival We Actually Needed

You’ll notice that everyone takes the tempi slightly differently. Some people treat the first movement as a leisurely stroll; others treat it like a brisk walk. There’s no "right" way, which is the beauty of the Prokofiev Violin Sonata 2. It’s flexible enough to handle different personalities.

Actionable insights for enthusiasts and performers

If you're an audience member, look for the "cat and mouse" games between the instruments. In the finale, notice how the violin and piano trade off these explosive rhythmic motifs. It’s almost like they’re trying to out-shout each other before coming together for the big finish.

For students or teachers:

- Study the Flute Score: Seriously. Looking at the original Op. 94 will show you exactly what Prokofiev added and what he changed. It helps you understand which parts of the violin version should feel "light" and "airy."

- Balance the Dynamics: The piano part is dense. In many modern halls, the piano can easily swallow the violin. Work on the balance early in the rehearsal process.

- Embrace the Irony: Don't play the pretty parts too seriously. There’s always a little bit of a "wink" in Prokofiev’s writing.

This sonata remains a staple because it captures a specific moment in history—a moment where a composer under immense political pressure decided to write something purely, stubbornly beautiful. It’s a testament to the idea that music doesn't always have to reflect the darkness of its time. Sometimes, it can be the light that helps you get through it.

To really get inside the head of a composer like Prokofiev, it helps to realize he wasn't trying to change the world with this specific piece. He was just trying to write a damn good sonata. And in doing so, he gave the violin world one of its most enduring gifts. Whether you’re a pro or just someone who likes to listen while you drink your coffee, the Prokofiev Violin Sonata 2 has something for you. It’s sophisticated, it’s fun, and it’s just a little bit weird. Exactly like the man who wrote it.

Check out the score, find a good recording, and just let the music do the talking. You won't regret the 25 minutes you spend with it. It’s one of those rare pieces that feels fresh every single time you hear it, no matter how many times you’ve been through the "wrong notes" and the soaring D-major themes.