You've probably been there. Your team spends three months building a feature, launching a marketing campaign, or restructuring a department, only to realize the "fix" didn't actually fix anything. It’s frustrating. It's expensive. Honestly, it’s usually because you started running before you knew where the finish line was. Most people think they know what a problem is, but they rarely take the time to actually pin it down. That’s where the definition of problem definition comes in—it sounds like academic jargon, but it’s actually the difference between a genius pivot and a total waste of money.

Basically, a problem definition is the formal process of identifying the gap between where you are and where you want to be. It’s not just "we're losing money." That's a symptom. A real definition digs into the why, the who, and the so what. If you can't describe the problem in two sentences without using buzzwords, you don't have a definition; you have a complaint.

Charles Kettering, the legendary head of research for General Motors, famously said that a problem well-stated is a problem half-solved. He wasn't being poetic. He was being practical. When you narrow the scope, the solution often stares you right in the face.

What Most People Get Wrong About Problem Definition

We are hardwired to be "fixers." In a high-pressure business environment, "thinking" often feels like "stalling." If you’re sitting in a meeting and say, "Let’s spend another week defining this," someone is going to roll their eyes. They want action. But action without definition is just expensive guessing.

One of the biggest mistakes is confusing the definition of problem definition with a "solution in disguise."

For example, a manager might say, "The problem is we don't have an AI chatbot." No. That’s a solution. The problem might be that customer wait times are over twenty minutes, or that support staff are overwhelmed by repetitive queries. By defining it as "lacking a chatbot," you’ve already killed every other potential solution, like improving the FAQ page or hiring more staff. You've blinded yourself.

Nuance matters here. A good definition is "solution-agnostic." It describes a state of affairs, not a missing tool. It focuses on the pain, not the medicine.

The Core Elements of a Tight Definition

If you want to do this right, you need to look at specific dimensions. Harvard Business School professor Clayton Christensen often talked about the "Jobs to be Done" framework. This is a great way to approach a definition. What "job" is the customer or the business trying to do that they currently can't?

The Gap Analysis

Every problem is a gap.

- Current State: "We are here." (e.g., 15% churn rate)

- Desired State: "We want to be here." (e.g., 5% churn rate)

- The Barrier: "This is what's stopping us." (e.g., users find the onboarding process too technical)

The Stakeholders

Who is actually bleeding? Sometimes the person complaining isn't the one with the problem. If a CEO says the problem is "low productivity," but the employees say the problem is "broken software," you have two different definitions. You have to decide which one is the root. Honestly, it's usually the one closest to the actual work.

Constraints and Scope

A definition that is too broad is useless. "The problem is our company culture" is a nightmare to solve. It’s too big. "The problem is that the engineering team doesn't receive clear specifications from product managers, leading to 20% rework" is something you can actually fix. You need boundaries. What is not part of this problem?

Why the Definition of Problem Definition Varies Across Industries

In medicine, a problem definition is a diagnosis. If a doctor defines your problem as "stomach pain," they haven't done their job. They need to know if it's an ulcer, stress, or a pulled muscle. The definition dictates the surgery.

In software engineering, this often takes the form of "Requirements Gathering." If the developer defines the problem differently than the user, you get a "perfect" piece of software that nobody wants to use. It’s the classic "The operation was a success, but the patient died" scenario.

In social sciences, it's about framing. Look at how we talk about "urban poverty." If the problem is defined as "lack of character," the solutions are educational and moral. If the problem is defined as "lack of access to capital," the solutions are economic and systemic. The way you define the problem literally creates the reality of the solution.

The "Five Whys" and Other Tools That Actually Work

You've probably heard of the Five Whys. It was developed by Sakichi Toyoda and used heavily at Toyota. It’s simple, but people rarely do it because it feels awkward.

- Why is the machine stopped? (A fuse blew.)

- Why did the fuse blow? (The bearing was overloaded.)

- Why was the bearing overloaded? (It wasn't lubricated enough.)

- Why wasn't it lubricated enough? (The pump wasn't pumping.)

- Why wasn't it pumping? (The shaft was worn.)

If you stopped at the first "Why," you’d just change the fuse. And it would blow again an hour later. That’s the power of a deep definition of problem definition. It gets you to the worn shaft, not just the blown fuse.

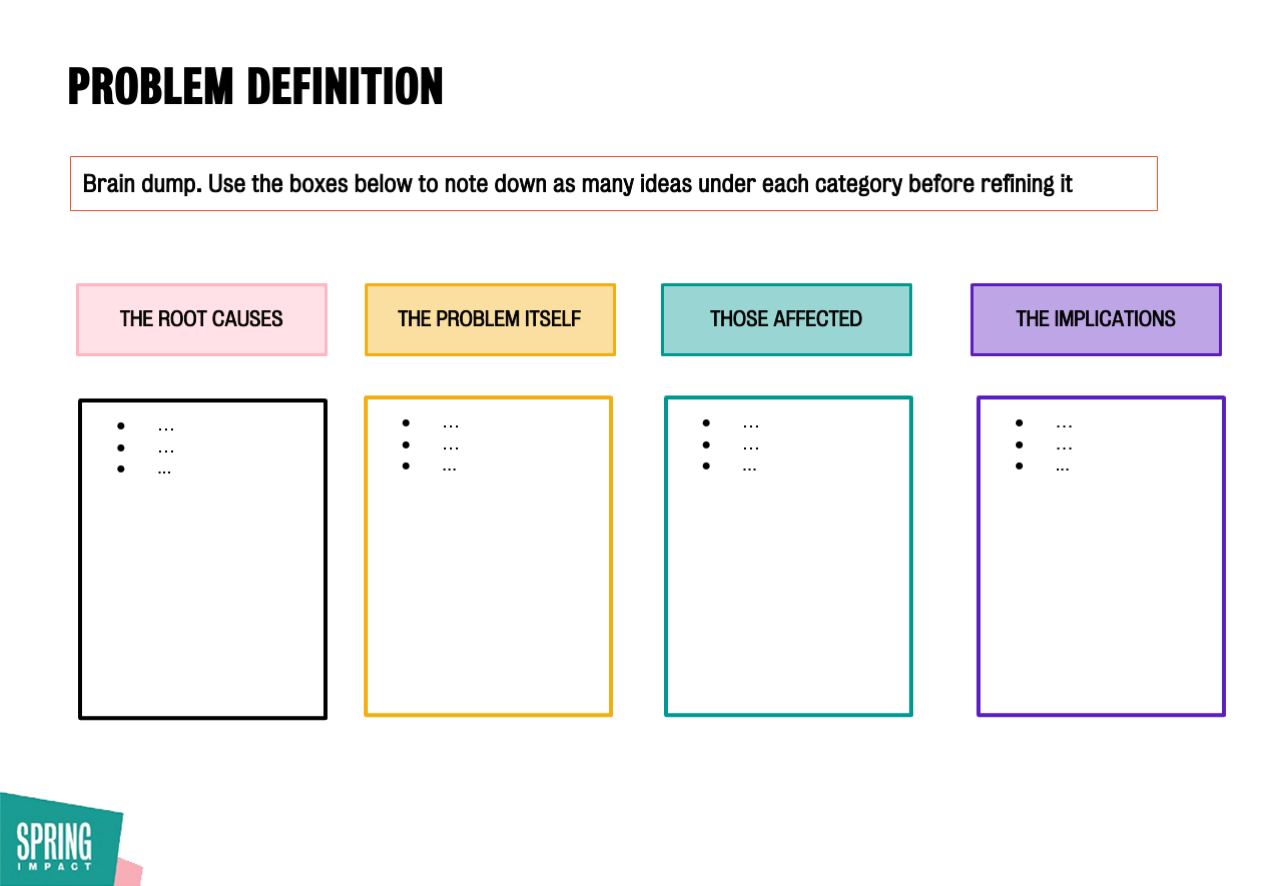

Another tool is the "Problem Statement Canvas." It’s a bit more formal but keeps teams aligned. You list the context, the impact, and the "success criteria." If you can't measure success, your problem isn't defined well enough yet. You need numbers. You need dates. You need specific outcomes.

Cognitive Biases That Mess With Your Head

We aren't as logical as we think. Several biases actively work against us when we try to define problems.

Anchor Bias: We get stuck on the first piece of information we hear. If a client says "our website is slow," we define the problem as a technical performance issue. We might ignore the fact that the actual problem is the confusing navigation, which makes the user feel like the site is slow because they can't find what they want.

Availability Heuristic: We define problems based on recent events. If we just dealt with a security breach, every new problem looks like a security threat.

Confirmation Bias: We define the problem in a way that confirms what we already believe. If a manager thinks a certain employee is lazy, they will define a drop in team output as a "personnel issue" rather than a "supply chain delay."

To fight these, you need a "Devil's Advocate." You need someone in the room whose only job is to say, "What if the problem is actually the exact opposite of what we just said?"

A Real-World Example: The Slow Elevator

There’s a classic case study in management circles about a building where tenants complained that the elevators were too slow.

The initial definition: "The elevators are too slow."

Solutions: Faster motors, better algorithms, or installing more elevators. All were incredibly expensive.

The redefined problem: "The wait is annoying."

Solution: They put mirrors next to the elevators.

People stopped complaining because they were distracted by looking at themselves. The "problem" wasn't the mechanical speed; it was the psychological boredom of waiting. By changing the definition of problem definition, the building owners saved hundreds of thousands of dollars. They solved the human problem, not the mechanical one.

The Risks of Getting It Wrong

What happens when you skip this?

You get "Solution Fatigue." This is when a company tries ten different things, none of them work, and the staff becomes cynical. They start to think nothing will work. But the issue wasn't the effort; it was the target.

👉 See also: Reince Priebus Net Worth: What Most People Get Wrong

You also waste "Opportunity Cost." Every hour spent solving the wrong problem is an hour you didn't spend solving the right one. In a competitive market, that's a death sentence. While you're fixing your "speed" problem by installing mirrors, your competitor might be fixing the "location" problem by moving to a better building. You have to be sure you're fighting the right war.

Step-by-Step: How to Write a Problem Statement That Works

Don't overcomplicate this. Use a simple template to get started, but be prepared to iterate.

- Identify the "Ideal": In a perfect world, how would this process look?

- State the "Reality": What is happening right now? Be brutal. Use data.

- Quantify the "Consequences": What is this costing us? Time? Money? Reputation? Employee burnout?

- Draft the "Statement": "We aimed for [Goal], but [Reality] is happening because [Root Cause], resulting in [Impact]."

Keep it under 50 words. If it's longer than that, you're still rambling.

Actionable Insights for Your Next Project

Stop the meeting. Seriously. The next time you're in a "solutioning" session, pause and ask everyone to write down what they think the problem is on a sticky note.

You will be shocked. If you have ten people, you’ll likely get eight different definitions. That’s your first problem. You can't solve a mystery if everyone is reading a different book.

- Interview the front lines: Don't just look at dashboards. Talk to the people who deal with the problem every day. They usually know the "Why" better than the "Who."

- Write it down: A verbal definition is a ghost. It changes every time someone speaks. Put it in writing and put it on the wall.

- Check your ego: Are you defining the problem to make yourself look good, or to actually fix the mess? Be honest.

- Review and Revise: As you learn more, change the definition. It's not a contract; it's a compass. If the compass is pointing the wrong way, turn it.

The definition of problem definition isn't about being smart; it's about being disciplined. It's about having the guts to say "I don't know what's wrong yet" instead of pretending you have all the answers. In the long run, the person who spends the most time understanding the problem usually spends the least time fixing it.

Next Steps for Implementation

Start by auditing your current projects. Take your top three active initiatives and try to write a one-sentence problem statement for each. If you find that an initiative is "to implement [X] software," stop. Redefine it based on the pain that software is supposed to alleviate. If you can't find the pain, you might be working on a "ghost project" that doesn't need to exist at all. Move your resources to the problems that actually have a measurable impact on your bottom line or your users' lives.