History has a funny way of flattening people into footnotes. If you’ve heard of the assassination at Sarajevo—the spark that blew up the world in 1914—you know about Archduke Franz Ferdinand. But most people totally breeze past his kids. Especially Ernst. Prince Ernst of Hohenberg wasn't just some pampered royal hanging around a palace waiting for a crown that would never come. He was a man who ended up in a concentration camp because he refused to shut up about what he believed in.

He was the youngest son. Born in 1904, his life started with a silver spoon and ended up facing down the SS. It’s a wild story, honestly.

The Sarajevo Trauma and the Hohenberg Exile

Imagine being ten years old and losing both parents to an assassin's bullet. That was Ernst's reality. Because his mother, Sophie Chotek, wasn't of "equal birth" to the Archduke, the Habsburg rules were brutal. Ernst and his siblings, Maximilian and Sophie, were basically sidelined. They weren't considered dynastic heirs to the Austro-Hungarian throne. This "morganatic" status meant they were insiders who were also perpetual outsiders.

When the shots rang out in Sarajevo, the kids were at Belvedere Palace. They didn't just lose their parents; they lost their status. After the war ended and the empire collapsed in 1918, the new Czechoslovakian government wasn't exactly feeling warm and fuzzy toward anyone named Hohenberg. They got kicked out. Exiled. They lost their estates at Konopiště and had to scramble to find a footing in a world that was rapidly turning its back on monarchy.

Ernst went to school. He studied law. He tried to live a life that made sense in a crumbling Europe. He was known for being the "joker" of the family—more easygoing than his older brother Max, but with a streak of stubbornness that would eventually get him into a lot of trouble.

👉 See also: Who's the Next Pope: Why Most Predictions Are Basically Guesswork

Why the Nazis Hated Prince Ernst of Hohenberg

By the 1930s, Austria was a mess. You had the Rise of the Fatherland Front, a lot of political infighting, and the looming shadow of Adolf Hitler across the border. Unlike a lot of aristocrats who thought they could "manage" the Nazis or use them to get their land back, the Hohenberg brothers weren't buying it.

They were staunch legitimists. Basically, they wanted the Habsburgs back, but they also believed in a sovereign Austria. They saw Hitler as a vulgar threat to everything they stood for.

Ernst didn't hide his feelings. He spoke out. He joined the Austrian resistance movements. When the Anschluss happened in March 1938—that’s when Germany officially annexed Austria—the Nazis didn't wait. They didn't care about his title. Or maybe they cared too much. They wanted to make an example of the sons of the man whose death started the Great War.

The Horror of Dachau

The arrest was quick. On April 1, 1938, both Ernst and Maximilian were deported to Dachau. Think about that for a second. These were the nephews of the late Emperor Franz Joseph, and they were suddenly wearing striped pajamas and pushing wheelbarrows full of stones.

✨ Don't miss: Recent Obituaries in Charlottesville VA: What Most People Get Wrong

The SS took a special, twisted pleasure in humilitating them. They were assigned to the "Scheisskompanie"—the latrine squad. They spent their days cleaning toilets with their bare hands while guards mocked their "royal" heritage.

Max was eventually released after about six months, largely due to international pressure and his wife’s tireless campaigning. But Ernst? Ernst was a different story. The Nazis kept him for much longer. He was transferred to Buchenwald and then back to Dachau. He spent years in the system.

Why? Because he was "unreformable." He wouldn't bow. He wouldn't sign papers supporting the regime. He stayed in the camps until 1943. Five years. That kind of experience changes a person’s DNA. He survived, but he wasn't the same man who went in. His health was wrecked. His spirit, though, remained surprisingly intact for a guy who had been through literal hell.

Life After the Wire

When he finally got out, he was kept under a sort of loose house arrest. He couldn't really do much until the war ended in 1945. After the liberation, you’d think he’d just want to retire and disappear, right?

🔗 Read more: Trump New Gun Laws: What Most People Get Wrong

Not Ernst.

He stayed active in Austrian politics. He was deeply involved in the Austrian People's Party (ÖVP). He cared about the reconstruction of his country. He eventually got married to Marie-Thérèse Wood, and they had two sons, Franz Ferdinand and Ernst.

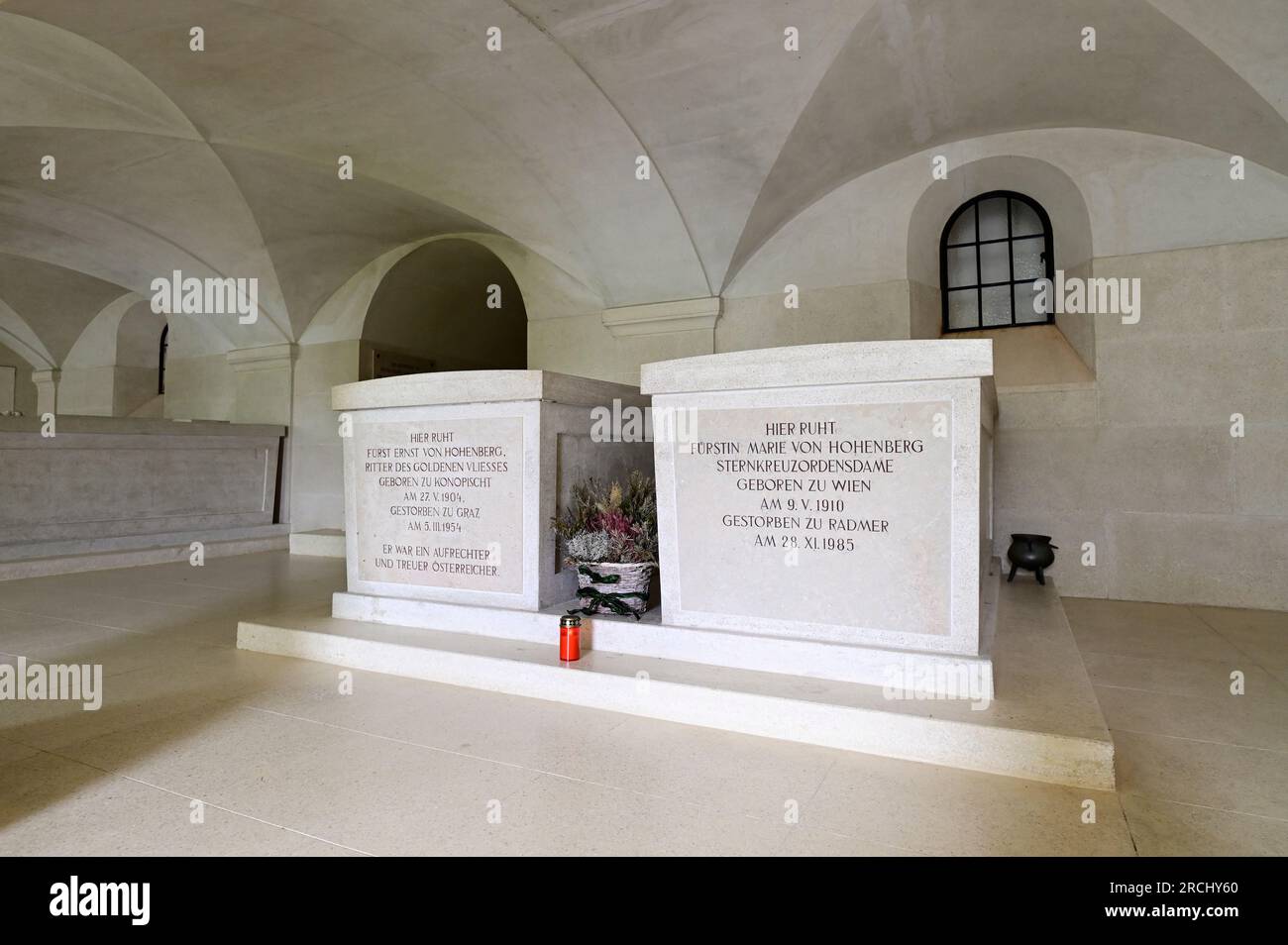

There's this misconception that all these old royals just sat around pining for the "Good Old Days." Ernst was more practical. He knew the empire was gone. He focused on ensuring the new Austria didn't fall back into the traps of extremism. He died in Graz in 1954, only 50 years old. Those years in the camps definitely shaved decades off his life.

What We Get Wrong About the Hohenbergs

A lot of historians treat the Hohenberg children as tragic victims or passive observers. That's a mistake. They were active participants in a resistance that cost them everything. Ernst wasn't just a "Prince." He was a political prisoner who chose a concentration camp over collaboration.

- He wasn't a "German Nationalist." Many Austrian nobles fell for the Pan-German trap. Ernst stayed loyal to the idea of a multi-ethnic, independent Austria.

- His survival wasn't "luck." It was a grueling daily battle of wills against the SS.

- The titles mattered less than the character. In Dachau, a prince's blood is the same color as anyone else's when a guard hits them. He lived that reality every day.

How to Explore This History Further

If you’re interested in the deeper nuances of the Hohenberg family and the Austrian resistance, you shouldn't just stop at a Wikipedia page. History is best understood through the locations and primary documents that survived the chaos of the 20th century.

- Visit Artstetten Castle: This is the family seat in Lower Austria. It’s where Franz Ferdinand and Sophie are buried because they weren't allowed in the Imperial Crypt in Vienna. The museum there has an incredible collection of personal items and documents that detail the lives of the children after 1914. It gives a very human face to the "Sarajevo orphans."

- Research the "Legitimist" Resistance: Look into the work of historians like Brooke-Shepherd. Understanding why the Nazis feared the return of the Habsburgs helps explain why Ernst was treated with such specific cruelty.

- Check the Dachau Memorial Archives: The records of the prisoners are meticulous. Seeing Ernst’s name on a transport list alongside common criminals and political dissidents is a stark reminder of the "leveling" effect of the Holocaust.

- Read up on the Anschluss: To understand Ernst, you have to understand the atmosphere of March 1938. It wasn't just a military parade; it was a systematic purge of anyone who represented the "Old Austria."

Ernst of Hohenberg represents a very specific type of courage. It’s the courage of someone who has everything to lose—status, wealth, safety—and decides that none of it is worth more than their integrity. He didn't have to be a hero. He could have stayed quiet and lived a comfortable, quiet life under the radar. He chose the hard path instead. That’s why we should remember him.