Prime factorization for 40 isn't exactly a topic that keeps people up at night. Honestly, most folks haven't thought about it since eighth-grade pre-algebra, yet it’s the backbone of how your credit card transactions stay secure and how computers talk to each other without losing their minds. When you break 40 down into its DNA, you aren't just doing "math homework." You're performing a fundamental operation that clarifies the very structure of the number itself.

It’s basic. But also kind of profound if you look at it the right way.

Why Prime Factorization for 40 Matters More Than You Think

Most people think of 40 as just a round number. It’s two score. It’s the number of winks in a nap. But in mathematics, the prime factorization for 40 is a specific set of building blocks that cannot be broken down any further. Think of it like chemistry. If 40 is a molecule, its prime factors are the atoms. You can’t slice an atom and keep the same element.

The actual result is $2^3 \times 5$. Or, if you want to be old school about it: $2 \times 2 \times 2 \times 5$.

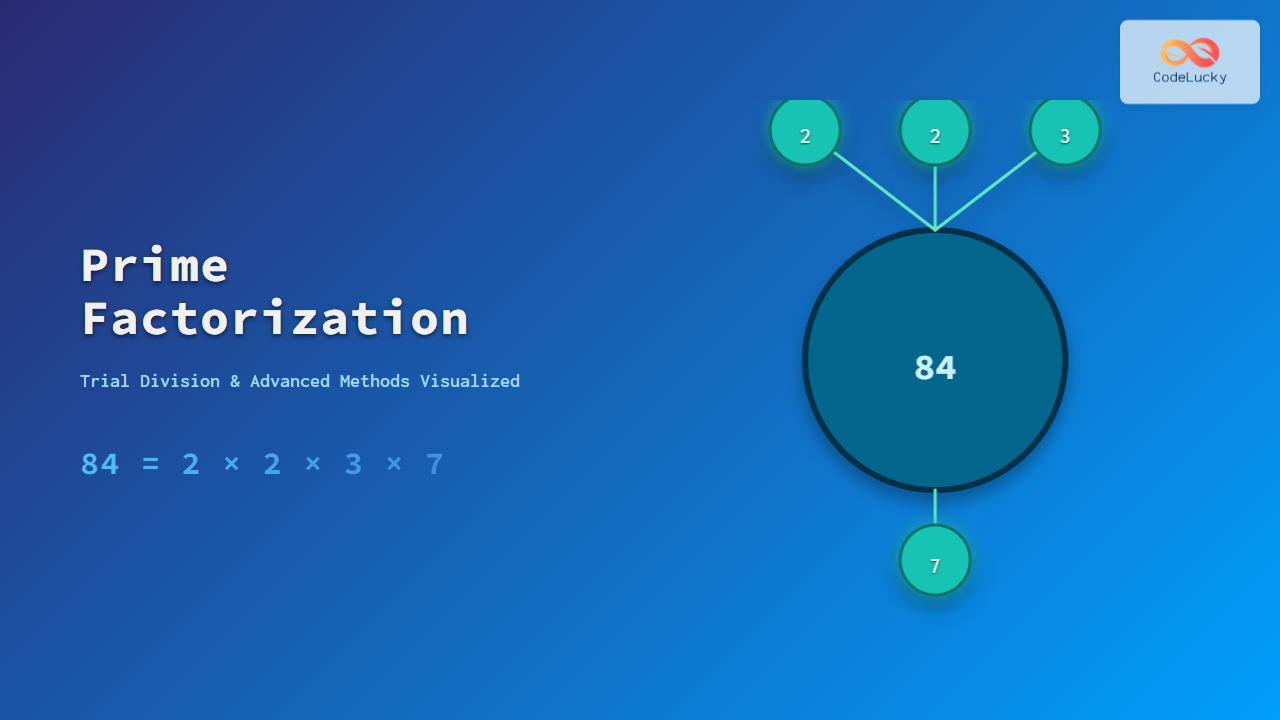

The Factor Tree Method (The Visual Way)

If you’re a visual learner, you probably remember the factor tree. It’s that sprawling, chaotic diagram that starts with a single number and branches out until you hit a dead end. For 40, you start by picking any two numbers that multiply to get there. Maybe you pick 4 and 10.

Now, look at those branches. Is 4 prime? No. It’s a composite number. You split it into $2 \times 2$. Both of those are prime, so that branch stops. What about 10? Again, not prime. You split 10 into $2 \times 5$. Both of those are prime.

Look at what’s left at the tips of the branches. You have three 2s and one 5.

It doesn't actually matter which numbers you start with. If you started with 2 and 20, you’d still end up at the exact same destination. That’s the Fundamental Theorem of Arithmetic in action. It basically says that every integer greater than 1 is either prime itself or can be represented by a unique product of prime numbers. There is no other combination of primes in the universe that will ever multiply to exactly 40.

The Upside-Down Division (The Clean Way)

Some people hate the messiness of trees. They prefer "ladder division" or the "cake method." You start with 40 and divide by the smallest prime number possible.

- 40 divided by 2 is 20.

- 20 divided by 2 is 10.

- 10 divided by 2 is 5.

- 5 divided by 5 is 1.

Once you hit 1, you're done. The column of numbers you used to divide—2, 2, 2, and 5—is your answer. It’s efficient. It’s clean. It’s the way engineers usually prefer to visualize the prime factorization for 40.

Common Misconceptions About Factors

A huge mistake people make is confusing "factors" with "prime factors." They aren't the same thing.

The factors of 40 are 1, 2, 4, 5, 8, 10, 20, and 40. Those are all the numbers that can divide into 40 without leaving a remainder. But prime factors are a specific subset. 4 isn't a prime factor. Neither is 10. They are composite.

Another weird thing? 1 is not a prime number.

I know, it feels like it should be. It’s "prime" in the colloquial sense of being first, but mathematically, a prime number must have exactly two distinct factors: 1 and itself. Since 1 only has one factor (itself), it doesn't count. So, when you're listing the prime factorization for 40, never include 1. It just clutters the math.

Real-World Applications

You might be wondering why anyone cares about this outside of a classroom.

Cryptography.

Modern encryption, like RSA, relies on the fact that while it’s easy to multiply two massive prime numbers together, it is incredibly difficult for a computer to do the reverse—finding the prime factorization of a giant number. While finding the factors of 40 is a split-second task for a human, finding the prime factors of a 200-digit number could take a supercomputer years.

📖 Related: Buying a TV LED Smart 4K? Here is What Salespeople Won't Tell You

Understanding the "why" behind 40 helps you grasp the "how" of the digital world.

Breaking Down the Math

When we write the result as $2^3 \times 5$, we’re using exponential notation. It’s just shorthand. It looks sophisticated, but it’s really just a way to avoid writing "2" over and over again.

- 2 is the smallest and only even prime number.

- 5 is a Fermat prime (a specific type of prime number that fits a certain formula).

When you combine three 2s, you get 8. Multiply that 8 by 5, and you’re back at 40.

Why the Number 40?

In many cultures and historical contexts, 40 is a "completion" number. In the Bible, it rained for 40 days and 40 nights. Lent is 40 days. In some biological contexts, pregnancy is roughly 40 weeks. Mathematically, it’s a composite number, an octagonal number, and a Harshad number (which means it’s divisible by the sum of its digits: $4 + 0 = 4$; 40 is divisible by 4).

Knowing the prime factorization for 40 gives you a deeper look into why this number behaves the way it does in division and patterns.

Practical Next Steps

If you want to master this, don't just stop at 40. Try these steps to solidify your understanding:

👉 See also: How to change primary email on Apple ID without losing your data

- Try the "Reverse" Method: Take the prime factors of another number, say 60 ($2 \times 2 \times 3 \times 5$), and see how many different factor trees you can draw that all lead to that same result.

- Check for Primality: Use the divisibility rules. If a number ends in 0, it’s always divisible by 2 and 5. This makes the prime factorization for numbers like 40, 50, and 100 much faster because you already know two of the "DNA" components.

- Use a Calculator Sparingly: Use tools like WolframAlpha to check your work, but try the ladder method by hand first. It builds a type of "number sense" that helps with mental math in daily life, like splitting a bill or calculating a tip.

Prime factorization is essentially the art of simplifying the complex. Once you can tear down a number like 40 into its core elements, you start seeing the underlying logic in every other mathematical system you encounter.