Ever noticed that tiny checkbox on your tax return asking if you want to send $3 to the Presidential Election Campaign Fund? Most people breeze right past it. Honestly, it feels like one of those weird relics of the 1970s, like disco or fondue sets. But that little box is actually the heartbeat of a massive, albeit struggling, experiment in American democracy.

You’ve probably heard people say it "costs you money" or "lowers your refund." That’s a total myth. Checking the box doesn't change your tax bill by a single cent. It just tells the Treasury to move $3 from the general tax pool into this specific bucket. It’s basically a way to say, "I want a tiny slice of my taxes to go toward keeping candidates away from big-money lobbyists."

The $3 Choice: Why Nobody Is Checking the Box Anymore

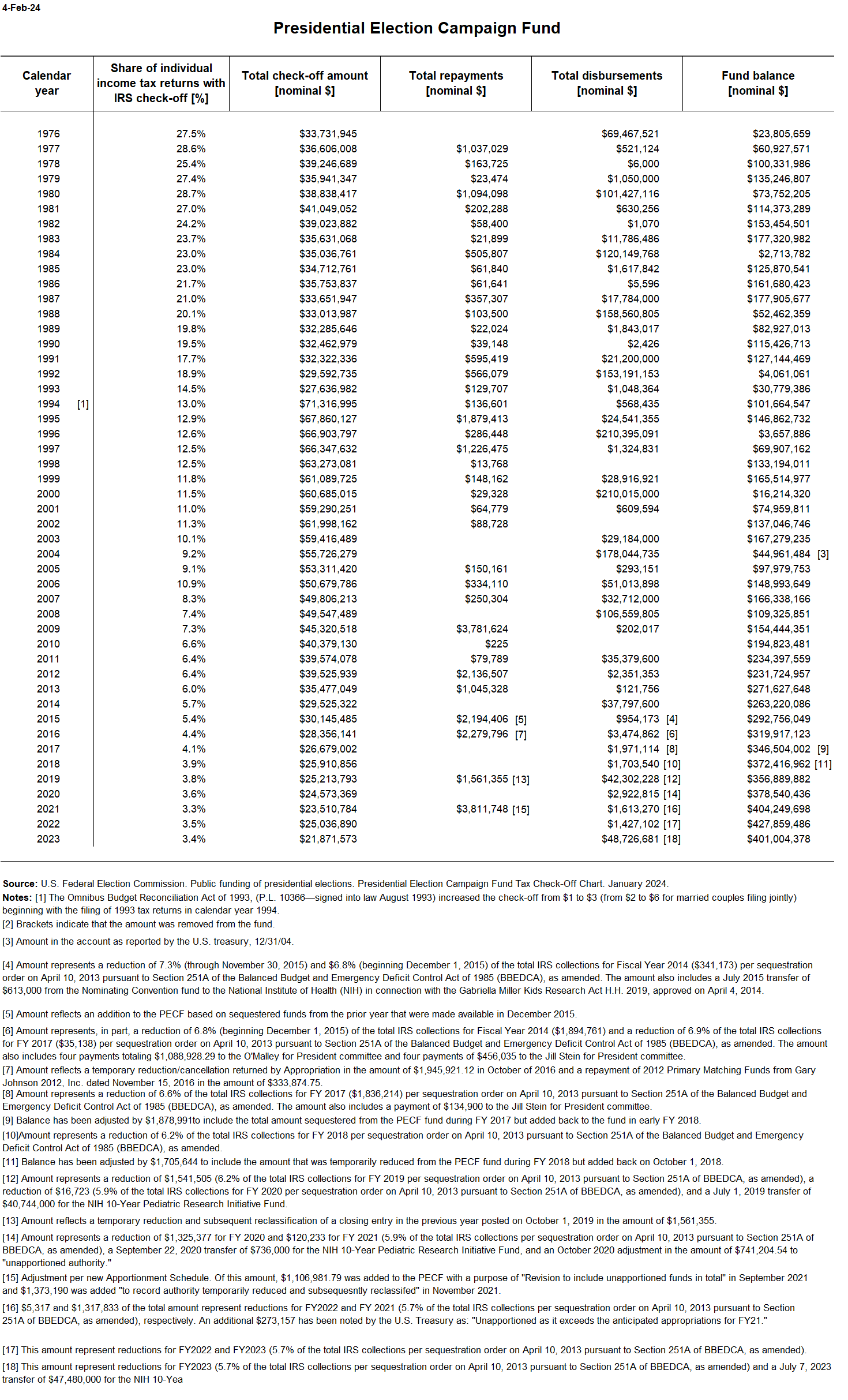

Back in the late 70s, nearly 30% of taxpayers were hitting that "Yes" button. People were still reeling from the Watergate scandal and liked the idea of a clean, publicly funded election. Fast forward to the 2020s, and that number has cratered. According to the FEC, participation has dropped to somewhere around 3.5%.

Why the ghosting? Part of it is just lack of awareness. But there’s a bigger, kinda cynical reason: the fund has become a bit of a dinosaur. In 2024, the general election grant was set at roughly $123.5 million. That sounds like a fortune, right? It’s not. Not in modern politics. When you have candidates raising $1 billion or more through private donations and Super PACs, $123 million feels like showing up to a Ferrari race on a tricycle.

If a major party candidate accepts that money, they have to stop raising private cash. They’re capped. For someone like Kamala Harris or Donald Trump in 2024, taking the "clean" money would have been a tactical suicide mission. They can raise ten times that amount on their own. So, the fund just sits there, growing dusty, while the candidates go where the big checks are.

📖 Related: What Really Happened With Trump Revoking Mayorkas Secret Service Protection

How the Money Actually Gets Used (When it Happens)

The fund isn't just for the big November showdown. It’s split into three main areas, though one of them got "hacked" by Congress a few years ago.

- Primary Matching Funds: This is for the early stages. If a candidate can prove they have broad support—raising over $5,000 in small donations in 20 different states—the government will match the first $250 of every individual contribution. It’s great for "outsider" candidates who need a boost to get off the ground.

- General Election Grants: This is the big lump sum for the final two nominees. But again, nobody has touched this since John McCain in 2008. Obama skipped it that year, realized he could raise way more privately, and changed the game forever.

- The Pediatric Research Pivot: Here’s a weird fact. Since 2014, the money that used to pay for the big party conventions (the balloons, the stages, the confetti) was diverted. Thanks to the Gabriella Miller Kids First Research Act, that money now goes to the National Institutes of Health for pediatric cancer research.

So, if you check the box today, you’re technically supporting a mix of potential candidate matching and kids' medical research. Not a bad deal for $0 out of pocket.

What Happens to the "Leftover" Cash?

People always ask what happens to the millions of dollars that candidates raise but don't spend. Politics is messy, and sometimes a campaign ends with a mountain of cash still in the bank.

The FEC is super strict here: no personal use. You can’t buy a beach house or a new Tesla with leftover campaign funds. Candidates usually do one of four things. They might save it for a future run, which is why you see some politicians with "zombie" accounts that stay active for years. They can also donate it to their political party, give it to other candidates (within certain limits), or hand it over to a charity.

👉 See also: Franklin D Roosevelt Civil Rights Record: Why It Is Way More Complicated Than You Think

For the Presidential Election Campaign Fund specifically, if the money isn't used by candidates, it just stays in the Treasury account for the next cycle. It doesn't disappear; it just waits for a candidate brave (or desperate) enough to accept the spending limits that come with it.

Current 2025-2026 Contribution Limits

If you're looking to skip the public fund and give directly to a candidate for the 2026 midterms or the next big race, the rules just changed. The FEC recently bumped the limits for the 2025-2026 cycle.

- Individual to Candidate: You can now give $3,500 per election. Since the primary and general count separately, that’s $7,000 total.

- National Party Committees: The limit is now $44,300 per year.

- PACs: Multicandidate PACs can still give $5,000 per election.

These numbers are indexed for inflation, which is why they keep creeping up every two years.

The Reality Check

Is public funding dead? Sorta. Unless Congress decides to massively increase the payout to match the "billion-dollar campaign" era, the fund will likely remain a ghost town for major candidates.

✨ Don't miss: 39 Carl St and Kevin Lau: What Actually Happened at the Cole Valley Property

However, for minor party candidates—the ones who get at least 5% of the vote—this fund is a lifeline. It’s the only way they can even dream of competing with the blue and red machines. If a third-party candidate hits that 5% threshold, they qualify for a proportional share of the funds, which can be the difference between a campaign that vanishes and one that actually builds a movement.

Your Next Steps

If you want to have a say in how this works, you've actually got a few options:

- Check the Box: Look for the Presidential Election Campaign Fund line on your next 1040. It doesn't cost you anything, and it keeps the option of public funding alive.

- Track the Money: Use the FEC.gov "Campaign Finance Data" portal. You can search for your own zip code and see exactly who your neighbors are funding. It’s surprisingly eye-opening.

- Small Dollar Power: If you hate the idea of big-money PACs, consider a small donation (even $10) to a candidate you like. The "matching funds" part of the system is designed to make those small checks count for more.

The system is definitely broken, but it’s the only one we’ve got. Whether you're checking the box or writing a check yourself, knowing where the money goes is the first step in not being cynical about the whole process.