History is messy. We like to think of the leaders of the free world passing away in quiet, dignified rooms, surrounded by weeping family and the heavy weight of legacy. Sometimes that's true. Other times, it's a chaotic scramble in a boarding house across from a theater or a sudden collapse on a bathroom floor. When you dig into the actual presidential death dates, you start to see patterns that feel almost too scripted to be real. It isn't just a list of numbers on a spreadsheet; it’s a bizarre collection of cosmic timing and medical mysteries.

Take the 4th of July. You probably know the trivia, but have you actually sat with how improbable it is?

In 1826, the United States was celebrating its 50th anniversary. Thomas Jefferson and John Adams, the two titans of the Revolution who had turned into bitter rivals and then late-life pen pals, were both fading. Jefferson went first at Monticello. A few hours later, unaware his friend had passed, Adams uttered his famous last words, "Jefferson survives," before dying himself. They died on the exact same day—the Golden Jubilee of the nation they built. Then, just five years later, James Monroe died on July 4th too. It’s the kind of thing a screenwriter would reject for being too "on the nose," yet it happened.

Why Certain Presidential Death Dates Feel Like a Glitch in the Matrix

It’s easy to get obsessed with the July 4th trio, but the calendar has other weird quirks. Honestly, if you look at the timeline of the early 19th century, death was an ever-present shadow. People forget how young these men were in "political years" compared to the gerontocracy we see today.

William Henry Harrison is the classic cautionary tale. He died just 31 days into his term. For years, the narrative was that he caught pneumonia because he was stubborn and didn't wear a coat during his two-hour inaugural address in the freezing rain. Recent medical analysis, specifically a 2014 study published in The Journal of Infectious Diseases by Jane McHugh and Philip A. Mackowiak, suggests something much grosser. They argue Harrison likely died of enteric fever caused by the White House's proximity to a literal marsh of raw sewage. The "death date" of April 4, 1841, wasn't a result of a cold; it was a result of bad plumbing.

📖 Related: Why Transparent Plus Size Models Are Changing How We Actually Shop

The Summer of Suffering

James A. Garfield’s death is perhaps the most frustrating. He was shot in July 1881, but he didn't actually die until September. His presidential death date of September 19 is a testament to the horrors of pre-antiseptic medicine. Doctors literally stuck their unwashed fingers into the wound looking for the bullet. Alexander Graham Bell—yes, the telephone guy—even brought an early metal detector to the White House to find the slug. It failed because Garfield was lying on a bed with metal springs, which the doctors didn't account for. The infection killed him, not the assassin's lead.

The Modern Era and the Shift in Longevity

The way we record and experience these dates changed with the advent of mass media. When JFK died on November 22, 1963, it wasn't a footnote in a weekly paper; it was a live trauma. That date is burned into the collective memory of an entire generation.

But look at the other side of the coin: longevity.

Modern medicine has stretched the gap between the end of a presidency and the final date on a headstone. Jimmy Carter has redefined the "post-presidency" entirely. As of early 2026, we are witnessing a record-breaking stretch of survival. For a long time, Herbert Hoover held the record for living 31 years after leaving office. Carter blew past that over a decade ago.

👉 See also: Weather Forecast Calumet MI: What Most People Get Wrong About Keweenaw Winters

Does the Stress Actually Kill Them?

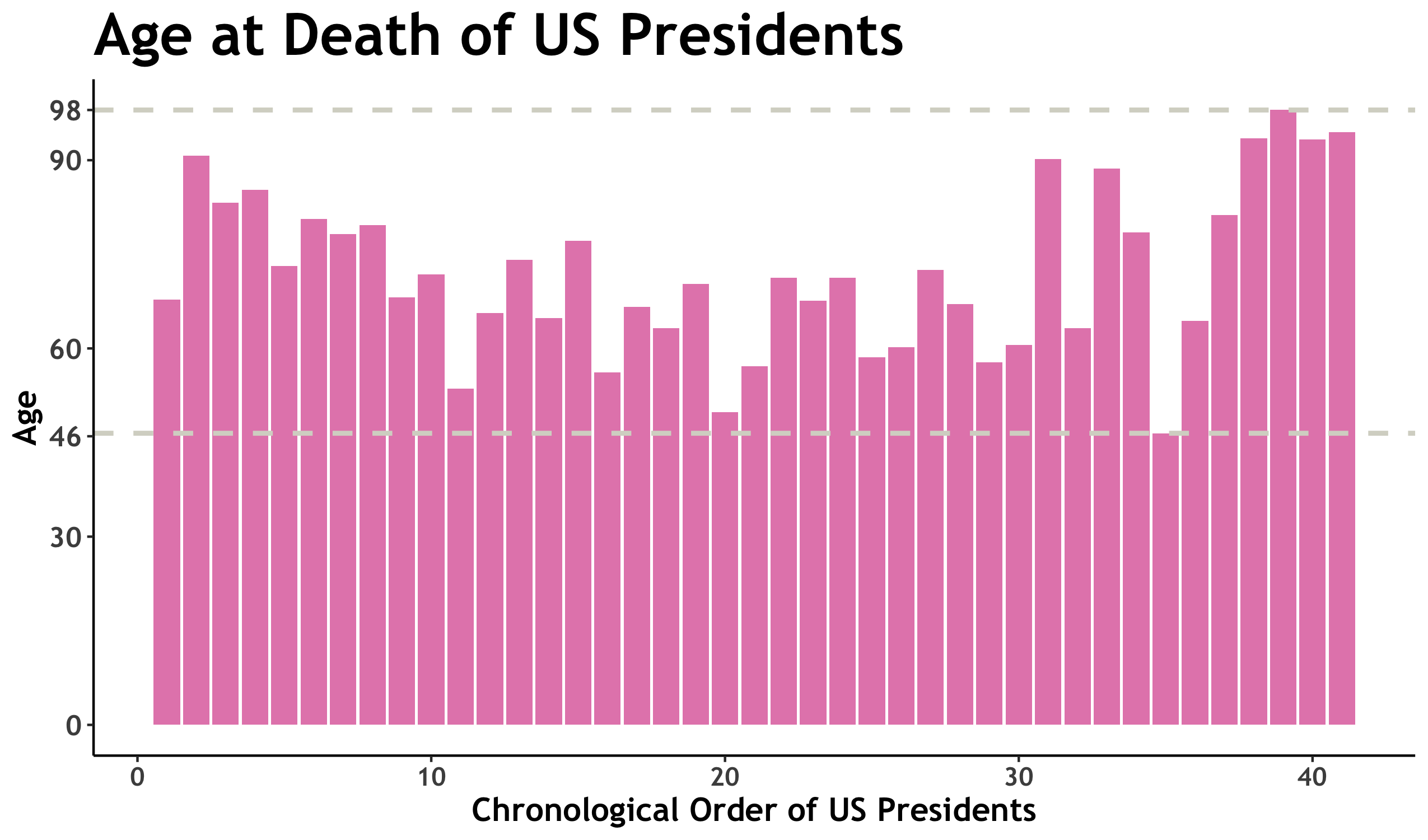

There is this persistent myth that the presidency "ages" a man and leads to an early grave. You've seen the side-by-side photos. Dark hair turns silver; skin sags. However, Dr. S. Jay Olshansky, a researcher at the University of Illinois at Chicago, found that most presidents actually live longer than their peers.

- They are usually wealthy.

- They have access to the best healthcare on the planet.

- They are typically highly educated, which correlates with lifespan.

Basically, while the job is a pressure cooker, the perks of the position act as a biological buffer. Except for the four who were assassinated and the four who died of natural causes in office, most former presidents enjoy a very long sunset.

Mapping the Trends

If you want to understand the timeline, you have to look at the clusters. We had a strange run in the early 1970s. Harry Truman died in December 1972. Just a month later, Lyndon B. Johnson died in January 1973. It felt like the mid-century version of the country was being swept away all at once.

Then you have the outliers.

✨ Don't miss: January 14, 2026: Why This Wednesday Actually Matters More Than You Think

- John Tyler: He died in 1862 during the Civil War. Because he had joined the Confederacy, he is the only president whose death wasn't officially mourned in Washington D.C. at the time. He’s buried under a Confederate flag.

- Richard Nixon: His death in 1994 marked the end of a very long, very complicated attempt at career rehabilitation.

- George H.W. Bush: He died in late 2018, just months after his wife Barbara. There’s a medical phenomenon called "broken heart syndrome," or takotsubo cardiomyopathy, that often strikes long-married couples. While his official cause of death was related to Parkinson’s, the timing is a classic human story.

What You Can Actually Do with This Info

If you're a history buff, a teacher, or just someone who likes winning bar trivia, don't just memorize a list of dates. That’s boring. Instead, look at the historical context of each presidential death date to understand the state of the union at that moment.

Step 1: Visit the Sites

You can't truly feel the weight of this history through a screen. Most presidential gravesites are part of the National Park Service or private foundations. Mount Vernon (Washington) and Monticello (Jefferson) are the big ones, but places like the James A. Garfield National Historic Site in Ohio give you a much more intimate look at the tragedy of a life cut short.

Step 2: Use the Digital Archives

The Miller Center at the University of Virginia has an incredible repository of "Life Before the Presidency" and "Death of the President" essays. They go into the gritty, unvarnished medical details that textbooks skip. If you want to know exactly what the doctors found during the autopsy of Zachary Taylor (to debunk those arsenic poisoning rumors), that's where you go.

Step 3: Track the "Living Presidents" Metric

Keep an eye on how many former presidents are alive at any given time. The record is six. This happened during the Trump administration and again briefly during the Biden years. It’s a fascinating barometer of political transition.

The timing of a death often defines a legacy as much as the life itself. Lincoln’s death on Good Friday 1865 turned him into a secular martyr. FDR’s death in April 1945, just months before the end of WWII, left the world in a state of shock just as the nuclear age was dawning. These dates aren't just points on a line; they are the hinges upon which American history swung.

To dig deeper, start by visiting the National Archives online. Look up the specific funeral proceedings for the president you're most interested in. The logistics of a state funeral—the planning, the guest list, the train routes—reveal more about the era’s social hierarchy than almost any other event. Or, if you're near D.C., take a day trip to Congressional Cemetery. Not many presidents are there, but the "cenotaphs" designed by Benjamin Henry Latrobe for early congressmen give you a visceral sense of how the capital used to mourn its leaders.