You’ve seen him. Every time you pull a twenty-dollar bill out of your wallet, there he is—the wild hair, the intense gaze, the vibe of a man who just survived a duel (which he probably had). But honestly, the version of the seventh president we carry around in our pockets is only a tiny slice of the story.

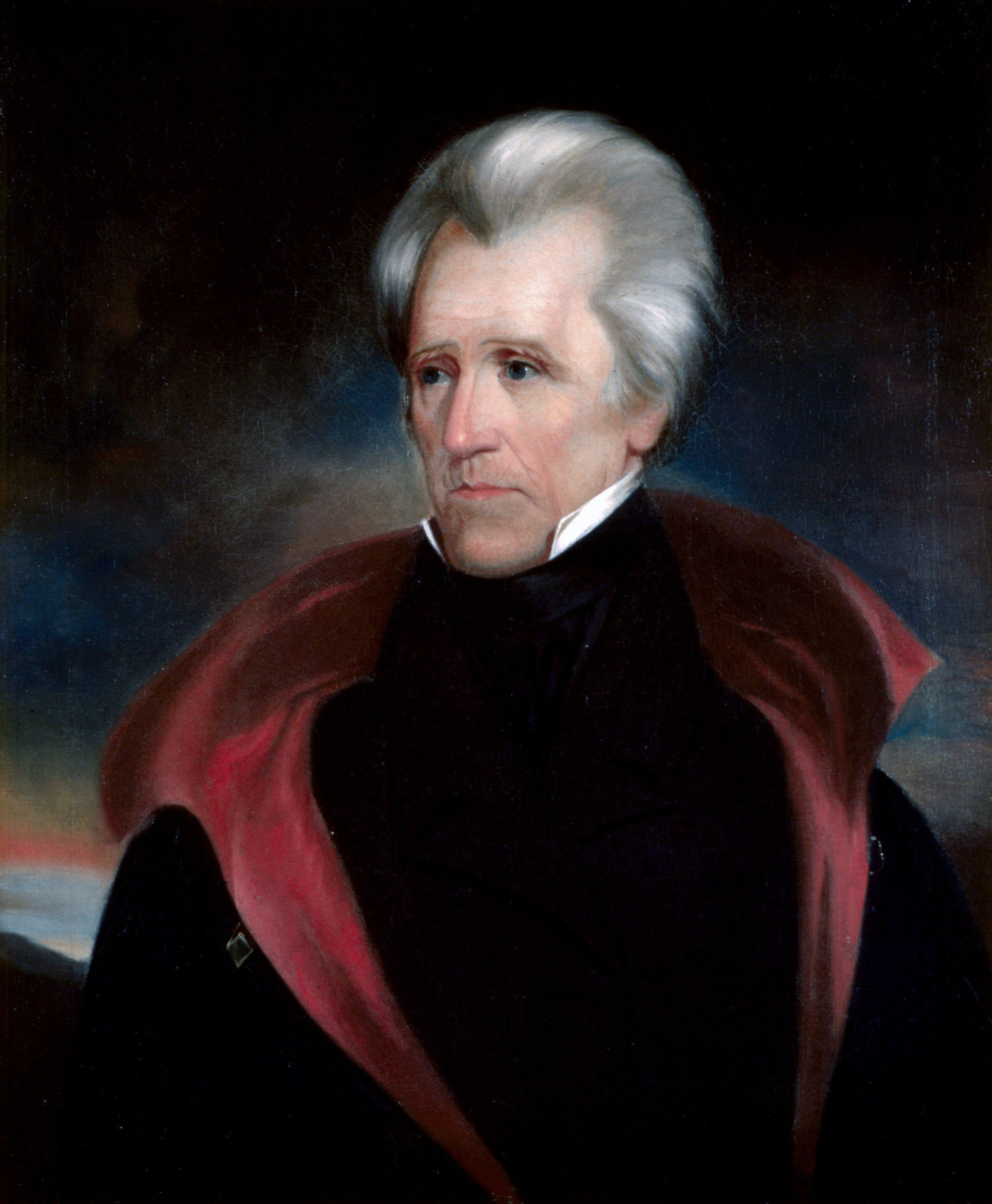

When people search for president andrew jackson pictures, they usually expect a standard gallery of stiff, 19th-century oil paintings. What they find instead is a weirdly complex PR campaign that started two centuries ago and hasn’t really stopped.

He was the first "common man" president, yet he spent a staggering amount of time posing for artists to make sure he looked like an elite statesman. It's kinda ironic. He hated paper money, yet his face is now the literal definition of it.

The "Court Painter" and the Art of the Spin

Most of the president andrew jackson pictures you’ll find in museums like the National Portrait Gallery weren't just "captured moments." They were carefully managed.

Enter Ralph E.W. Earl.

Earl was Jackson’s "court painter." He lived at the White House for all eight years of Jackson’s presidency. That’s not a joke. He actually moved in. Earl was basically the 1830s version of a social media manager. He painted so many portraits of Jackson—standing, sitting, in uniform, in a suit—that people started calling him "the King’s painter."

Earl’s job was to take a man who had a reputation for being a violent, unrefined "backwoods" brawler and turn him into someone who looked like he belonged in a parlor. He created "Farmer Jackson" to appeal to the working class and "The National Picture" to make him look as dignified as George Washington.

📖 Related: Short Curly Single Braids: Why This Style Is Actually Taking Over Right Now

One of his most famous works from 1817 shows Jackson in full military regalia. It celebrates the hero of the Battle of New Orleans. But as Jackson moved into politics, Earl shifted the focus. He started painting Jackson in civilian clothes, looking more like a thoughtful patriarch than a general.

That Infamous $20 Bill Portrait

If you’re looking for the most famous president andrew jackson pictures, you have to look at Thomas Sully.

Sully didn't live at the White House, but he was the heavy hitter of the era. He first painted Jackson in 1824 when he was a senator. The portrait you see on the $20 bill today? It’s actually based on an 1845 painting Sully did right before Jackson died.

The U.S. Treasury didn't start putting Jackson on the twenty until 1928. There’s a lot of debate about why they chose him, especially since Jackson famously spent his presidency trying to destroy the Second Bank of the United States. He thought paper money was a scam. Now he's the face of it.

The Real Face: The Daguerreotypes

Paintings are one thing. They can be edited. The artist can smooth out the wrinkles or make the eyes look a little more heroic. But in 1845, a new technology arrived: the daguerreotype.

📖 Related: Finding the Best Hartford Road Pizza Manchester: What You Need to Know

Basically, the first "real" photos.

There are only about four surviving daguerreotypes of Jackson, and they are… intense. Taken at his home, The Hermitage, just months before he died, they show a man who was toothless, constantly in pain, and utterly exhausted.

- The Dan Adams Portrait (April 15, 1845): This is the one that usually shocks people. Jackson is propped up against a pillow. He looks grumpy. He actually reportedly said, "Humph! Looks like a monkey!" when he saw it.

- The Edward Anthony Version: This was later copied by the famous Mathew Brady. It shows Jackson in a dark cloak, his hair still wild and white, looking like a ghost of his former self.

These photos are the most honest president andrew jackson pictures we have. They strip away the "Hero of New Orleans" mythology and show a 78-year-old man who had lived through multiple wars, countless duels, and the brutal politics of the 1830s.

Why the Images Are Still Controversial

History isn't static. In 2026, we look at these pictures differently than people did in 1926.

For a long time, the portraits of Jackson were seen as symbols of American strength and the expansion of democracy. Today, critics and historians point to the "Trail of Tears" and Jackson’s aggressive Indian Removal policies. When you look at a romanticized painting of him now, you’re seeing the "purposeful effort to make him into who he was not," as Smithsonian curator Philip Kennicott once put it.

There was a big push a few years back to replace him on the $20 bill with Harriet Tubman. The plan was to move Jackson to the back of the bill. As of now, he's still there, staring out with that same piercing look.

Where to See Them for Yourself

If you’re a history nerd and want to see these in person, you’ve got options:

- The National Portrait Gallery (Washington D.C.): They have the "America’s Presidents" exhibit. It’s the only place with a portrait of every single president.

- The Hermitage (Nashville, TN): This was Jackson’s actual home. You can see where those final daguerreotypes were taken and view many of Ralph Earl's original works.

- The White House Collection: They own the 1835 Earl portrait and the 1817 John Wesley Jarvis painting.

Actionable Insights for Your Search

If you are looking for high-quality president andrew jackson pictures for a project or just curiosity, don't just stick to Google Images.

💡 You might also like: Natural Long Grey Hair: What Most People Get Wrong About the Transition

Go to the Library of Congress digital archives. They have the high-resolution scans of the original daguerreotypes. They are public domain, so you can zoom in and see the actual texture of his skin and the fraying of his collar.

Check the National Gallery of Art website. They have an "Open Access" policy, meaning you can download the Thomas Sully paintings in massive file sizes for free. It's way better than a grainy screenshot.

Comparing the Earl paintings to the Dan Adams photograph is a great exercise. It shows you exactly how much "filtering" went on in the 19th century. One is the image he wanted to leave behind; the other is the man he actually was.