You’ve probably seen it. That dry, gray, slightly metallic-tasting slice of meat at a holiday dinner that requires a gallon of gravy just to swallow. It’s a tragedy. Honestly, preparing leg of lamb for roasting shouldn’t be a gamble, but most home cooks treat it like a chore rather than a process. They buy the meat, rip off the plastic, and shove it in the oven. Stop doing that.

Lamb is expensive. It’s also a muscle that works hard, which means it has character, fat, and connective tissue that need respect. If you want that blushing pink interior and a crust that actually tastes like something, you have to start long before the oven dial even turns.

The Bone-In vs. Boneless Debate

Most people go for boneless because it’s easier to carve. I get it. But you’re losing flavor. A bone-in leg of lamb acts like a heat conductor. The bone heats up and helps cook the meat from the inside out, which often results in a more even roast. Plus, the marrow and connective tissue around the bone add a depth of flavor you just won't get from a net-wrapped lump of meat.

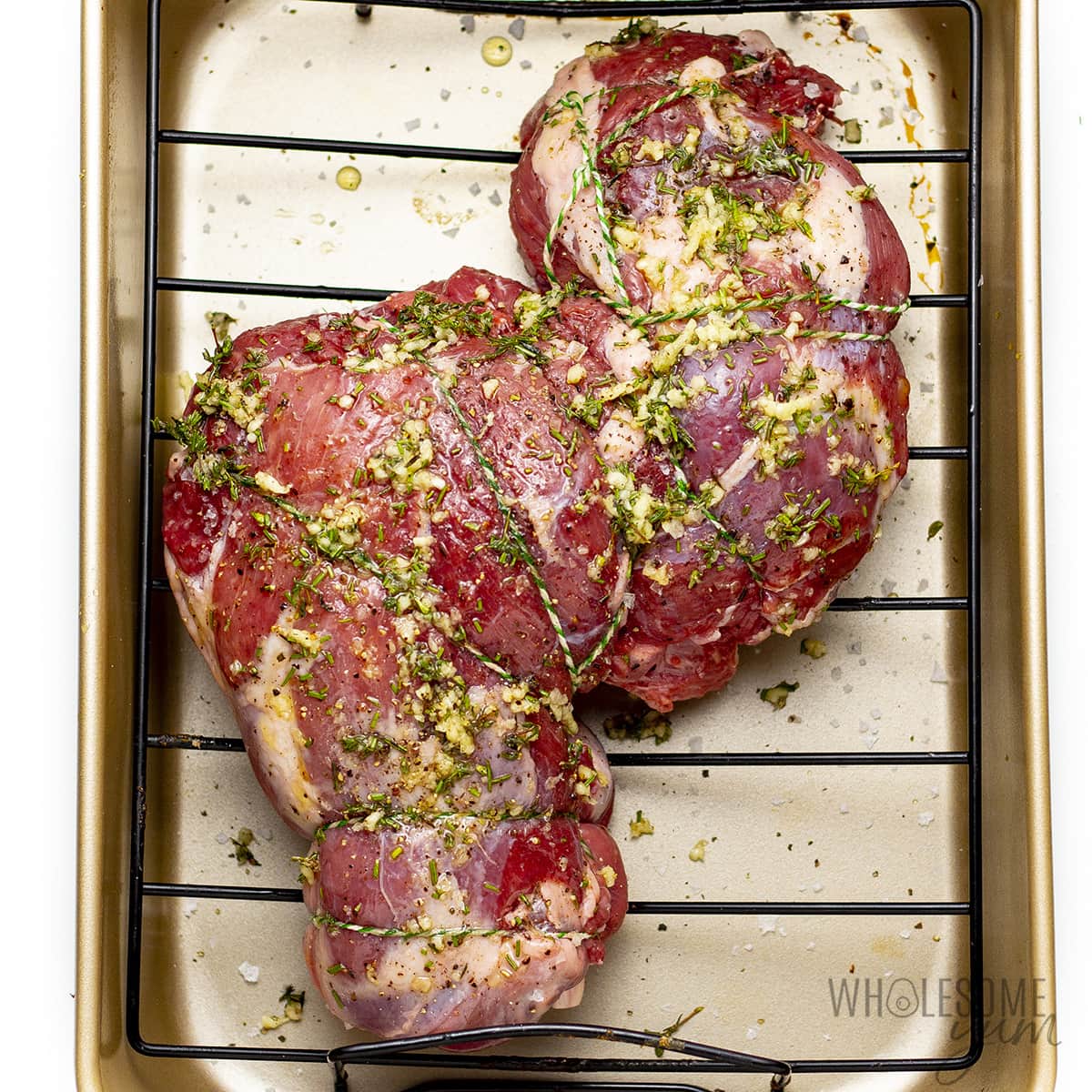

If you do go boneless, make sure it’s tied tightly. If it’s floppy, it’ll cook unevenly. One end will be shoe leather while the middle is raw. Use kitchen twine. Don't be shy about it. Loop it every inch or so to create a uniform cylinder. This is the first real step in preparing leg of lamb for roasting that actually matters for the final texture.

📖 Related: Why the Princess of Wales in Philippa Lepley for the State Dinner was a Royal Fashion Reset

The Secret is the Surface

Ever notice that weird, thin white skin on the outside of the lamb? That’s the "fell." Some butchers remove it; some don't. You want it gone. It’s papery and can have a funky, overly "muttony" taste that ruins the experience for people who think they don't like lamb. Take a sharp knife—I mean a really sharp paring knife—and slip it under that skin to peel it away.

Fat is good, though. Don’t trim every bit of white off the meat. You want a thin layer, maybe an eighth of an inch, to baste the meat as it roasts. Without it, the roast dries out. Simple as that.

Salt is a Time-Release Tool

Do not salt your lamb right before it goes in the oven. That’s a rookie mistake. Salt needs time to penetrate. If you salt the surface five minutes before roasting, the salt draws moisture out to the surface, where it evaporates, leaving the inside bland.

Instead, salt it at least 24 hours in advance. Use Kosher salt. Rub it in. Put the lamb on a wire rack in the fridge, uncovered. This does two things:

- The salt travels into the muscle fibers, seasoning the whole roast.

- The air in the fridge dries out the skin.

A dry surface equals a crispy crust. It’s science. If the surface is wet when it hits the heat, it steams. Steamed lamb is sad lamb. You want Maillard reaction—that beautiful browning that happens when proteins and sugars get hit with high heat.

🔗 Read more: Finding the Gucci Factory Outlet in Los Angeles: What Most People Get Wrong

Building the Flavor Profile

Lamb loves aromatics. Garlic is non-negotiable. Don't just rub it on the outside; it’ll burn and turn bitter. Take your paring knife and poke deep, narrow slits all over the roast. Stuff slivers of raw garlic and small sprigs of fresh rosemary into those holes.

As the lamb roasts, the fat melts around the garlic and rosemary, carrying those oils deep into the meat. It's like a flavor injection system.

- Anchovies: Trust me on this. Finely chop two or three anchovies and mix them into your herb rub. You won't taste fish. You'll taste a massive hit of "umami" that makes the lamb taste more like itself.

- Lemon Zest: It cuts through the heavy fat.

- Dijon Mustard: Use it as a binder for your herbs.

Temperature Control is Everything

You cannot cook a leg of lamb by time. I don't care what the recipe card says. "20 minutes per pound" is a lie because every oven is different and every leg of lamb has a different shape.

Buy a meat thermometer. A good one.

When preparing leg of lamb for roasting, you need to understand the carry-over cook. If you want medium-rare (around 130°F to 135°F), you must pull that lamb out of the oven when the internal temperature hits 125°F. The heat on the surface of the meat will continue to move inward while it rests, raising the internal temp by another 5 to 10 degrees.

The Importance of the Rest

This is where the impatient fail. If you cut into a leg of lamb the second it comes out of the oven, all the juice will run out onto the cutting board. Your plate will be a puddle and your meat will be dry.

Let it rest for at least 20 to 30 minutes. Tent it loosely with foil. This allows the muscle fibers to relax and reabsorb the juices. It’s the difference between a "good" roast and a "legendary" one.

Practical Next Steps for Your Roast

Now that you know the theory, here is how you actually execute this for your next dinner.

First, check your equipment. You need a heavy roasting pan and a rack. You don't want the lamb sitting in its own rendered fat, or the bottom will be soggy. If you don't have a rack, make one out of thick-cut onions, carrots, and celery.

Second, get the lamb out of the fridge an hour before you plan to cook. Cold meat in a hot oven results in uneven cooking. Let it come to room temperature. This is vital.

Third, start high, then go low. Blast the lamb at 425°F for about 15 or 20 minutes to get the browning started. Then, drop the temperature to 325°F for the remainder of the cook. This ensures a crusty exterior and a tender, juicy interior.

Finally, carve against the grain. Look at the meat; the muscle fibers run in one direction. Slice perpendicular to those fibers. This makes the meat much easier to chew and gives it a better mouthfeel. If you have a bone-in leg, slice down to the bone and then run your knife along the bone to release the slices.

Don't overthink it. Focus on the salt, the temperature, and the rest. The lamb will do the rest of the work for you.