It’s the most recorded gospel song in history. Honestly, it’s not even close. When you look at the Precious Lord Take My Hand song lyrics, you aren't just looking at a Sunday morning hymn. You’re looking at a suicide note that turned into a prayer.

Thomas A. Dorsey wrote it. Not the big band leader Tommy Dorsey, but the man known as the "Father of Gospel Music." Before he was writing about the Lord, he was "Georgia Tom," a blues pianist playing in rowdy Chicago barrelhouses. He lived a double life. Saturday night was for the blues; Sunday morning was for the pews. But in 1932, his world didn't just crack. It shattered.

Dorsey was scheduled to be the featured soloist at a giant revival meeting in St. Louis. He left his pregnant wife, Nettie, at home in Chicago. During the performance, a messenger ran onto the stage with a telegram. It was brief. It was brutal. His wife had died during childbirth. He rushed home, only to find that his newborn son had passed away just hours after the mother.

He was done. Dorsey swore he’d never write another note of music. He felt God had ghosted him. He told his friends he was going back to the jazz clubs because the church hadn't saved his family. But a few days later, while sitting at a piano in the quiet of a friend's music room, the melody came. The words followed.

Why These Lyrics Hit Differently Than Other Hymns

Most hymns from that era were stiff. They were formal. They used "thee" and "thou" and felt like they were written by people who had never had a bad day in their lives. Dorsey changed that. He brought the "blue note" into the sanctuary.

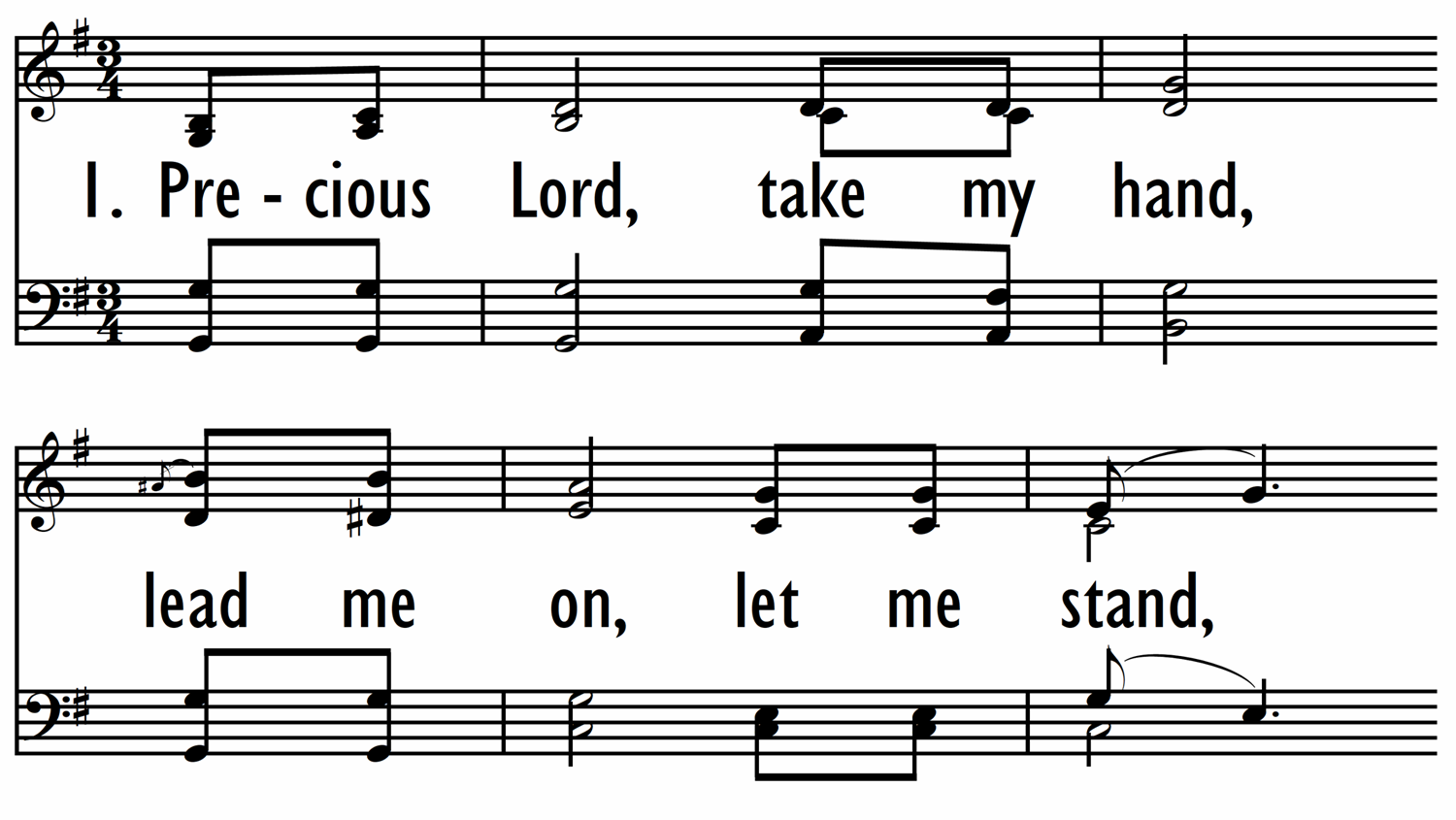

When you read the Precious Lord Take My Hand song lyrics, you notice they are remarkably simple. "Precious Lord, take my hand / Lead me on, let me stand." It’s the language of a child who is lost in a grocery store. There is no ego here. There is no complex theology. It is a desperate plea for basic stability.

The song actually borrows its melody from an older 1844 hymn tune called "Maitland" by George N. Allen. But Dorsey slowed it down. He added the swing of the Southside Chicago blues. He made it ache.

👉 See also: The Real Story Behind I Can Do Bad All by Myself: From Stage to Screen

- The Weariness: "I am tired, I am weak, I am worn." This isn't just physical fatigue. It's the spiritual exhaustion of a man who has buried his entire world in a single weekend.

- The Darkness: "Through the storm, through the night." He’s acknowledging that the light hasn't come yet. He’s still in the tunnel.

- The Request: "Take my hand." This is the core of the song. It’s a surrender of agency.

Mahalia Jackson, the greatest gospel singer to ever live, made this her signature song. She sang it at the funeral of Martin Luther King Jr. because it was his favorite. It’s been covered by everyone from Elvis Presley to Aretha Franklin to Beyoncé. Why? Because everybody knows what it feels like to be "worn."

The Blues Roots of a Sacred Classic

Dorsey was a pioneer because he realized that the pain in a blues club and the pain in a church are the exact same pain. They just have different solutions.

When he first started shopping his "gospel songs" around Chicago, the established preachers hated them. They called it "devil's music" brought into the house of God. They didn't like the syncopated rhythms. They didn't like how raw the lyrics were. They wanted songs about the Pearly Gates, not songs about being "weak and worn."

But the people in the pews? They couldn't get enough. They were living through the Great Depression. They were migrating from the Jim Crow South to the cold, industrial North. They didn't need a lecture; they needed a hand to hold.

A Breakdown of the Verses

- The First Verse: This is the setup. It establishes the physical and mental state of the singer. You can almost hear the heavy sigh before the first note.

- The Second Verse: "When my way grows drear / Precious Lord, linger near." This is about the fear of abandonment. When you're grieving, you don't just feel sad; you feel invisible.

- The Third Verse: "At the river I stand / Guide my feet, hold my hand." This is the traditional "crossing over" imagery common in African American spirituals, referencing the Jordan River or the transition from life to death.

Dorsey’s genius was in the phrasing. He didn't write "I am experiencing a period of melancholy." He wrote "I am tired." That’s the difference between a textbook and a masterpiece.

The MLK Connection and the Civil Rights Era

It is impossible to talk about the Precious Lord Take My Hand song lyrics without talking about the Civil Rights Movement. It became the unofficial anthem of the weary activist.

✨ Don't miss: Love Island UK Who Is Still Together: The Reality of Romance After the Villa

On April 4, 1968, moments before he was assassinated on the balcony of the Lorraine Motel, Martin Luther King Jr. leaned over the railing. He saw musician Ben Branch in the courtyard. King asked him to play "Precious Lord" at the meeting that night. He told him, "Play it real pretty."

It was the last thing he ever said.

When Mahalia Jackson stood to sing it at his funeral, she didn't just sing. She wailed. She channeled the grief of an entire nation into Dorsey's lyrics. That moment cemented the song as more than just a hymn; it became a historical monument. It showed that the song could carry the weight of a national tragedy just as easily as it carried the weight of one man’s lost wife and child.

Technical nuances of the melody

Musically, the song is a marvel of restraint. It usually stays within a single octave. This makes it accessible. You don't have to be an opera singer to sing it. You just have to be able to groan.

If you’re a musician looking to play it, the key is the "vamp." In gospel music, the vamp is where the singer repeats a phrase over and over, building emotional intensity. With "Precious Lord," the vamp usually happens on the phrase "Take my hand." It becomes a rhythmic chant. It’s meant to induce a trance-like state of comfort.

Interestingly, Dorsey didn't want it to be a fast song. Never. He used to get annoyed when choirs would try to "jazz it up" too much. He wanted the listener to feel every syllable of the word "precious."

🔗 Read more: Gwendoline Butler Dead in a Row: Why This 1957 Mystery Still Packs a Punch

Common Misconceptions

- Did he write it alone? Mostly, though as mentioned, the tune was adapted. He credited the inspiration to a higher power, often saying the music "fell out of the sky."

- Is it just a "funeral song"? People think so, but Dorsey wrote it as a "survival song." There’s a big difference. One is for the dead; the other is for those left behind.

- The Elvis Version: Elvis’s 1957 recording is actually very faithful to the original slow tempo. It helped introduce the song to a white, secular audience who had never heard of Thomas Dorsey.

How to use these lyrics for personal reflection

If you're looking at these lyrics today, maybe you're not just curious about the history. Maybe you're the one who is "tired, weak, and worn."

The power of the song isn't in the answers it gives. It doesn't actually give any answers. It doesn't explain why bad things happen. It doesn't justify the loss of Dorsey's wife or King's life.

Instead, it offers a physical gesture: holding a hand. In psychology, we talk about "grounding techniques" for people having panic attacks. This song is essentially a spiritual grounding technique. It’s about finding one point of contact when everything else is spinning out of control.

Actionable Insights for Using the Song

- Listen to the 1968 Mahalia Jackson version. It is the definitive emotional benchmark. If you want to understand the "soul" of the lyrics, start there.

- Read the lyrics as poetry. Strip away the music and just read the words. Notice the lack of multi-syllabic words. It’s a masterclass in "less is more."

- Journal through the "Worn" list. Dorsey identifies three states: Tired, Weak, and Worn. If you're using this for reflection, ask yourself which one you are today. "Worn" is the most interesting—it implies something that was once strong but has been used until it’s thin.

The Precious Lord Take My Hand song lyrics remind us that it’s okay to be at the end of your rope. Dorsey was there. He almost stayed there. But he reached for the piano keys instead of the exit door, and in doing so, he gave the world a way to talk to God when they've run out of fancy words.

To truly appreciate the depth of this work, compare it to Dorsey's earlier blues hits like "Tight Like That." The contrast shows the transformation of a man's soul through the crucible of grief. He didn't lose his blues; he just gave them a destination.

Next time you hear it, remember the telegram in St. Louis. Remember the man who wanted to quit. And remember that sometimes, the best things we ever create come from the moments when we are the most broken.

To deepen your understanding, research the "Chicago Gospel" movement of the 1930s. It provides the essential cultural context for why Dorsey’s specific style of "Precious Lord" was so revolutionary for the African American church at the time. You can also look into the work of the Thomas A. Dorsey National Convention of Gospel Choirs and Choruses, which still preserves his specific "Dorsey Style" of performance to this day.