The 1930s was a mess. Let’s be real. Between the global economic collapse of the Great Depression and the ominous drumbeat of a second World War, you’d think art would have just curled up and died. Instead, we got some of the most aggressive, beautiful, and weirdly optimistic visual communication in history.

Posters from the 1930s weren't just "pretty pictures" for a bedroom wall. They were survival tools. They were screaming for your attention from brick walls and subway stations, trying to convince you to buy a train ticket, join a labor union, or trust the government again. Honestly, if you look at a poster from 1935 and compare it to a sleek tech ad from today, you can see the DNA. It’s all there. The bold fonts. The simplified shapes. The way they used color to make you feel like everything was going to be okay, even when it definitely wasn't.

The Federal Art Project and the "Work Pays America" Vibe

When FDR launched the New Deal, he didn't just want to build bridges. He wanted to employ artists. The Works Progress Administration (WPA) created a specific division called the Federal Art Project (FAP), and this is where things get interesting.

Before this, posters were mostly lithographs—expensive and slow. But the WPA artists leaned hard into screen printing. It was cheap. It was fast. It allowed for those flat, vibrant blocks of color that we now associate with "vintage" style. Artists like Anthony Velonis basically championed the serigraph as a fine art form during this era. They weren't just making announcements; they were creating a brand for the United States government.

🔗 Read more: The Apple Crisp Recipe New York Times Readers Keep Obsessing Over

You've probably seen the National Parks posters. They have that iconic, layered look. Deep greens for the forests of Yellowstone, burnt oranges for Zion. Those posters were meant to encourage "domestic tourism" because, well, nobody could afford to go to Paris. They sold the American landscape as a cathedral for the common man. It worked.

The WPA produced over 2,000 designs, and over 2 million posters were printed. That’s a staggering amount of ink. But it wasn't just about trees. They tackled public health, too. "Clean Your Teeth!" or "Keep Your Teeth Clean!" posters were everywhere. It sounds silly now, but in the 30s, basic hygiene was a massive public health push. The designs were often stark—maybe just a giant toothbrush and a minimalist face—indebted to the European avant-garde but simplified for a weary American public.

Art Deco vs. The Machine Age

While the WPA was busy with social uplift, the commercial world was obsessed with "Streamlining." This is the Art Deco influence, but evolved. Think of the 1933 Chicago World’s Fair. The posters for "A Century of Progress" are all about speed.

Lines are diagonal.

Everything looks like it’s moving at 100 miles per hour.

Trains look like silver bullets.

The Nord Express posters by A.M. Cassandre are the gold standard here. Cassandre was a genius. He understood that in a fast-moving world, people don't read; they glimpse. His 1930s work for rail companies and booze brands like Dubonnet used "kinetic" typography. He’d make the letters get bigger or smaller to suggest perspective or motion. It was basically the birth of modern graphic design. If you look at his 1935 poster for the SS Normandie, the ship looks like a massive, unstoppable wall of steel. It’s terrifying and majestic at the same time.

But there’s a nuance here most people miss. While French Art Deco was about luxury—champagne, silk, ocean liners—American Art Deco in the 30s was about "The Machine." We call it Streamline Moderne. It was more industrial. The posters reflected this with heavy shadows and a sense of weight. They wanted you to believe in the power of the factory.

The Darker Side: Propaganda and the Rise of Shadows

We can't talk about posters from the 1930s without acknowledging the elephant in the room: political radicalization. In Europe, the 1930s saw the poster become a weapon.

In Germany, the National Socialists were perfecting a horrific but effective visual language. They moved away from the "degenerate" modernism of the 1920s and back toward a hyper-idealized, pseudo-classical realism. On the flip side, the Soviet Union was churning out Constructivist-influenced posters that celebrated the worker as a literal giant.

👉 See also: Carrigan Funeral Home Obituaries: What Most People Get Wrong

The Spanish Civil War (1936–1939) was perhaps the peak of the 1930s "poster war." Organizations like the CNT-FAI used bold, woodcut-style graphics. These weren't polished. They were gritty. They used high-contrast blacks and reds to symbolize blood and revolution. When you look at these, you feel the desperation. There’s a famous poster by Carles Fontserè showing a worker with a raised fist that perfectly captures that "last stand" energy.

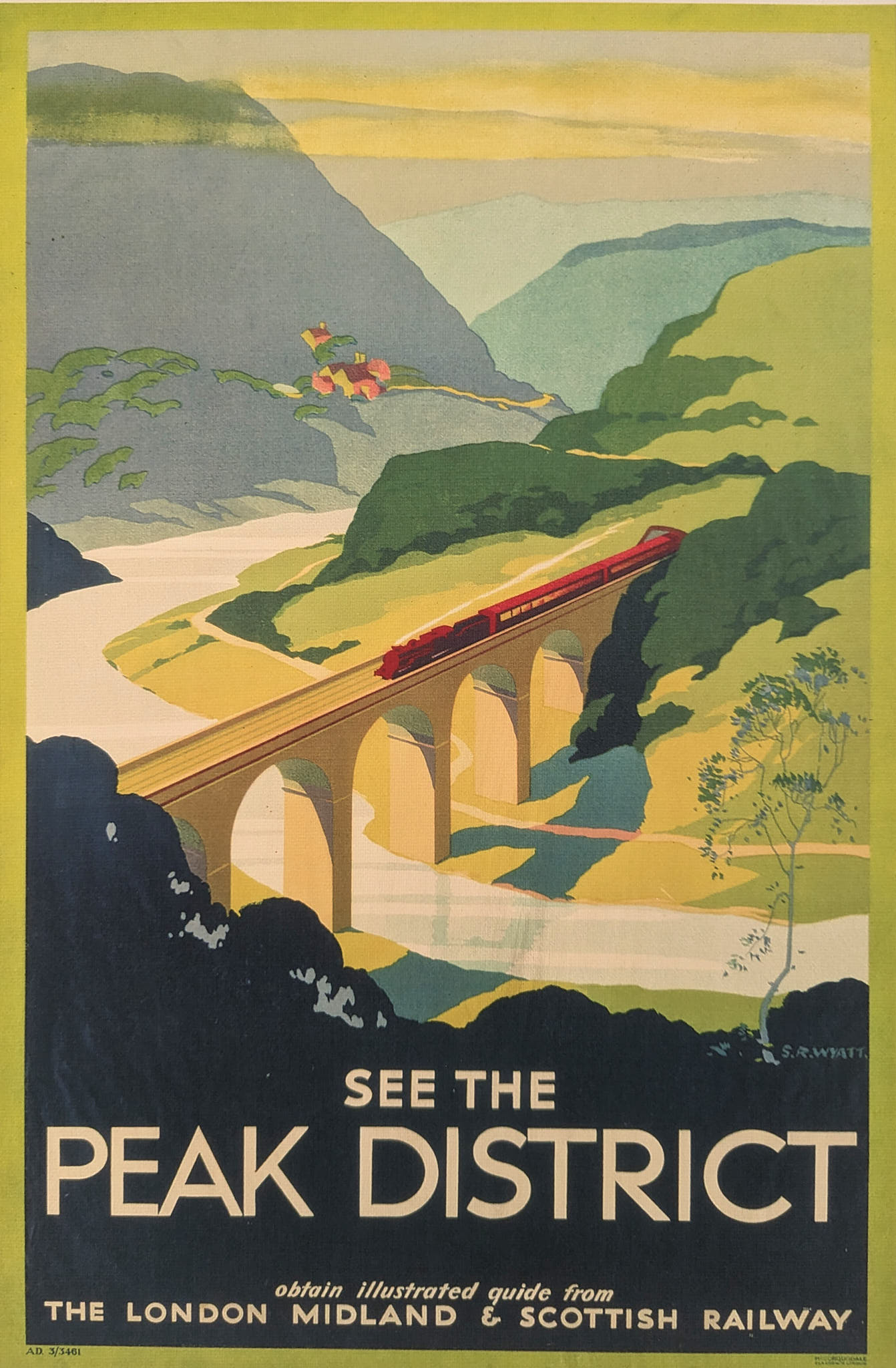

Travel Posters: Selling a Dream You Couldn't Afford

It’s kind of ironic. The decade with the least amount of disposable income produced the most beautiful travel advertisements.

Airlines like Pan Am or Imperial Airways were just starting to make long-distance flight a "thing" (for the ultra-rich, anyway). Their posters featured giant seaplanes landing in exotic lagoons. The color palettes were usually soft pastels—pinks, light blues, sandy yellows. They were escapism.

In the UK, the London Underground was a massive patron of the arts. They hired designers like Edward McKnight Kauffer. His work was incredibly sophisticated. He brought Cubism and Surrealism to the subway. Imagine being a tired office clerk in 1934, waiting for your train in the rain, and seeing a Kauffer poster that looks like a Picasso. It changed the visual literacy of the average person. You didn't have to go to a museum to see modern art; you just had to commute to work.

Typography and the "Big Bold" Revolution

If you hate "Live, Laugh, Love" fonts, you’d love the 1930s. This was the era of heavy-hitting sans-serifs.

- Futura (released in the late 20s but peaked in the 30s)

- Gill Sans

- Bifur

- Peignot

These typefaces were about clarity and authority. In the 30s, the "hero" of the poster was often the word itself. Designers started integrating text into the illustration. The smoke from a chimney might form the name of the company. A road might curve into the shape of a "S." This wasn't just clever; it was a psychological trick to make the message stick.

Why We Are Still Obsessed With Them

Why do people still pay thousands of dollars for an original 1938 travel lithograph? Why does every coffee shop in Brooklyn have a WPA reprint?

Kinda because we’re in a similar headspace now. The 1930s was a period of massive technological shift (radio, aviation) paired with massive anxiety. We're in that again. There’s something comforting about the solidity of 1930s design. The figures are strong. The colors are intentional. The messages are direct.

Also, it was the last era before photography took over everything. Most posters from the 1930s were hand-illustrated or used photo-montage (thanks to the Bauhaus influence). There’s a "human touch" there that a high-res digital photo can't replicate. You can see the brushstrokes. You can see where the screen-printing ink overlapped and created a third color by accident.

Spotting a Real 1930s Piece

If you're hunting at estate sales or online auctions, you've gotta be careful. "Vintage style" is a huge business, and fakes are everywhere.

Real posters from this era were usually printed on relatively thin, acidic paper. If it feels like a heavy, modern cardstock, it’s a reprint. Look at the edges under a magnifying glass. If you see a "dot pattern" (CMYK), it’s a modern digital print. 1930s lithographs or screen prints will have solid layers of ink or a very fine, irregular grain.

Also, check the size. Common sizes back then were "One-Sheet" (roughly 27x41 inches for movies) or "Double Crown" in the UK. If it’s a weird A4 or A3 size, it’s almost certainly a reproduction.

How to Collect and Use 1930s Aesthetic Today

You don't need a $10,000 budget to appreciate this. Honestly, the Library of Congress has digitized a huge chunk of the WPA archives. You can download them for free.

If you're a designer, look at the color harmonies. The 30s used a lot of "tertiary" colors—mustard yellows, teal blues, dusty maroons. They avoided the neon-brights of the 1960s or the muddy browns of the 1970s.

If you're a decorator, these posters work best when they aren't crowded. A single, large-scale 1930s travel poster can anchor a whole room. It’s about the balance of white space and heavy graphics.

Actionable Steps for Enthusiasts:

- Visit the Library of Congress Online: Search for the "Work Projects Administration Poster Collection." There are over 900 posters available in high resolution. It’s a goldmine of inspiration.

- Study A.M. Cassandre: If you want to understand modern layout, look at his work. Notice how he uses "vanishing points" to create a sense of scale.

- Check Local Archives: Many city libraries have local posters from the 1930s that were never national hits—stuff for local fairs, theater productions, or strike notices. These are often more "authentic" to the era's daily life than the famous ones.

- Invest in Linen Backing: If you do find an original, don't just frame it. Get it linen-backed by a professional. It stabilizes the old paper and flattens creases without damaging the art. It’s the industry standard for preservation.

- Look Beyond the US: Explore the "Grapus" precursors or the Swiss "Sachplakat" (Object Poster) style from the same era. It’s much more minimalist—often just one hyper-realistic object and a brand name.

The 1930s taught us that when the world is falling apart, art gets louder. These posters were the megaphone. They remind us that even in a "low" point in history, the visual world can be incredibly high-stakes and beautiful. Basically, they prove that good design isn't a luxury—it’s a necessity for getting through the day.

Preservation Note: Keep original posters out of direct sunlight. The inks used in the 1930s, especially the reds and yellows, are notoriously prone to UV fading. Use UV-protective glass or acrylic if you're hanging a piece of history on your wall.

Research Credit: For deep dives into the technical specs of 1930s printing, the works of Ellen Lupton and the archives at the Cooper Hewitt, Smithsonian Design Museum are the best resources available for verifying dates and designer attributions.