Death used to be a houseguest. Not a stranger in a sterile hospital room, but a presence in the parlor. When someone died in the 1860s, you didn't call a "specialist" right away; you washed the body yourself. You sat with it. And, quite often, you took a picture of it. This practice of post mortem Victorian era photography feels deeply macabre to us today. We scroll through grainy, sepia-toned images of children looking suspiciously still and feel a shiver. We’ve all seen the viral "creepy" lists claiming these bodies were propped up on secret stands to look alive.

Most of that is total nonsense.

Actually, the reality is much more heartbreaking. It’s about a culture where the mortality rate for children under five hovered around 25 percent in some urban areas. It's about a time when a photograph wasn't a casual selfie—it was an expensive, rare luxury. For many families, the post mortem Victorian era image was the only image they would ever have of their loved one. It wasn't about being morbid. It was about desperate, clinging love.

The myth of the "standing" corpse

Let’s tackle the biggest lie first. If you’ve spent any time on "spooky" history forums, you’ve seen the photos of people standing stiffly, supposedly held up by a visible metal rod behind their heels. People love to point at those and scream "Post mortem!"

Honestly? Those people were very much alive.

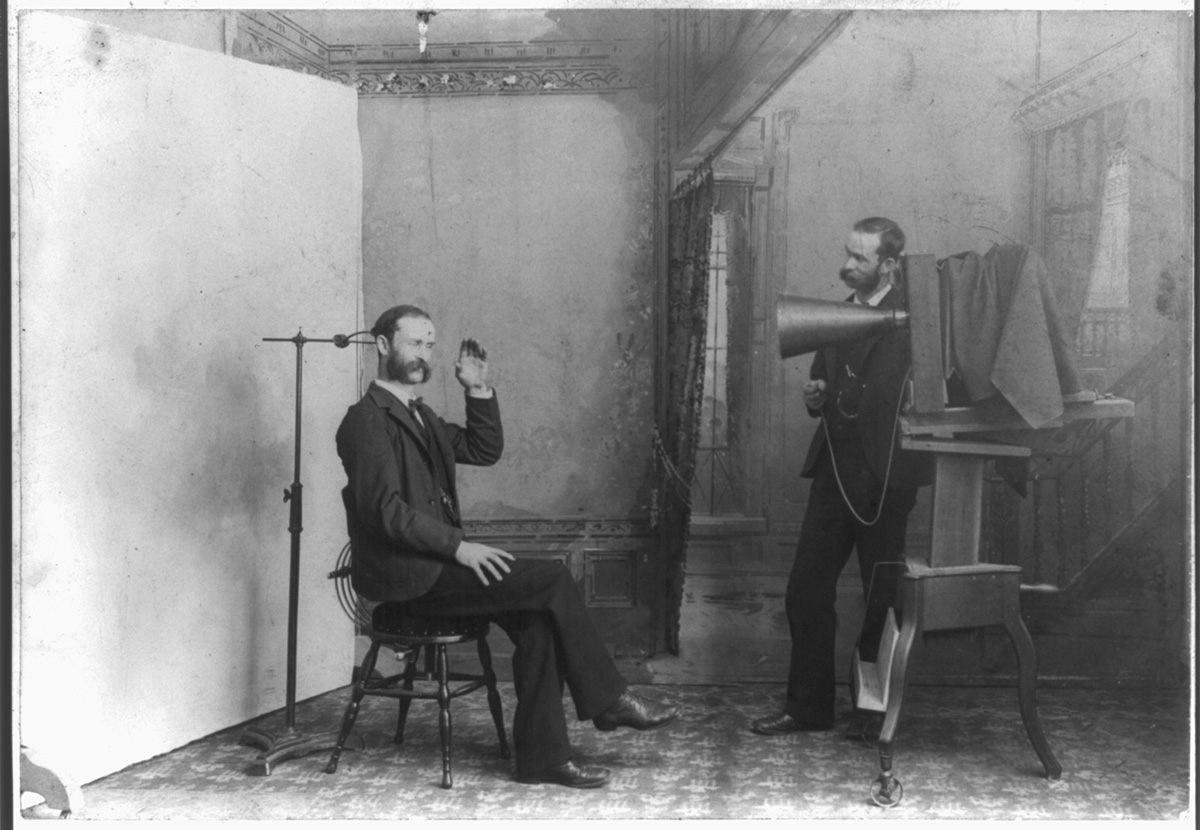

Those heavy metal stands were called "posing stands" or "head rests." Because early photographic exposures—like the daguerreotype or the ambrotype—took forever (sometimes several minutes), even the slightest sway of a living person would blur the image. The stand was there to keep a living, breathing person from ruining the shot. Think about it: a dead body is a "dead weight." A skinny metal rod designed to steady a head isn't going to hold up 150 pounds of limp human tissue. It just wouldn't work. Physics matters, even in the 19th century.

🔗 Read more: Finding the Right Word That Starts With AJ for Games and Everyday Writing

True post mortem Victorian era photos almost always show the deceased lying in a bed, resting on a sofa, or nestled in a casket. When photographers did try to make the deceased look "alive"—a style known as memento mori or "remember you must die"—they usually did it by posing them with their eyes closed, looking like they were in a "Last Sleep." Occasionally, they’d paint pink pupils onto the eyelids or add a flush to the cheeks on the final print. But they weren't out here propping bodies up like puppets.

Why they did it: The economics of grief

You’ve got to understand how rare a camera was. Before the Kodak Brownie came along in 1900 and democratized photography, having your picture taken was an Event. It was pricey. It required a trip to a studio or a commissioned visit from a photographer.

Imagine a family in 1870. They have a daughter. She dies of scarlet fever at age four. They realize, with a sickening gut-punch, that they don’t have a single visual record of her face. No sketches, no photos, nothing. The post mortem Victorian era photograph was the "last chance" to capture her likeness.

Historians like Audrey Linkman, author of The Dead Together, point out that these photos were treasured possessions. They weren't hidden away in a "creepy" box. They were displayed on mantels. They were sent to relatives in the mail like birth announcements. "Our little Mary has gone to the angels," the letter might say, accompanied by a photo of Mary looking peaceful in her lace Sunday best. It was a way of saying: She existed. She was here.

The shift in styles

Early on, in the 1840s and 50s, the focus was often on the face. Close-ups. Very intimate. As the century progressed, the "sentimental" Victorian culture took over. You started seeing more elaborate setups. Flowers—tons of them. Lilies were a favorite because they symbolized the restored innocence of the soul (and, practically speaking, they helped mask the smell).

💡 You might also like: Is there actually a legal age to stay home alone? What parents need to know

- The Last Sleep: The most common pose. Usually in a bed.

- The Mourning Mother: A heartbreaking sub-genre where a mother holds her deceased infant.

- The Casket Portrait: Later in the era, showing the body in a coffin became the standard, which actually feels more "normal" to us today.

Death was everywhere, so they got comfortable with it

We are a death-avoidant society. We hide it behind curtains. But the Victorians? They wore it on their sleeves. Literally. Queen Victoria spent 40 years in mourning clothes after Prince Albert died. This cultural obsession trickled down.

When someone died, the house went into lockdown. Clocks were stopped at the moment of death. Mirrors were covered with black crepe so the soul wouldn't get "trapped" in the reflection. Mourning jewelry was a huge industry—people would weave the hair of the deceased into intricate brooches or rings. Compared to a bracelet made of a dead person's hair, a photograph seems pretty tame, doesn't it?

The post mortem Victorian era was a time of transition. Medicine was improving, but not fast enough. Germ theory was just starting to take hold thanks to people like Joseph Lister and Louis Pasteur, but people were still dying of basic infections every single day. The photograph was a technology of memory. It was a weapon against the forgetting that happens when a person is buried in the ground.

How to tell if a photo is actually post mortem

If you’re a collector or just a history buff, you’ve got to be skeptical. The market is flooded with "fake" post mortem photos. Dealers know that "dead person" sells for more than "bored Victorian person."

- Look at the hands. Dead hands often look slightly swollen or are positioned very carefully to hide lividity.

- Check the eyes. If they look "painted on" or extremely blurry while the rest of the face is sharp, it might be a post mortem shot where the photographer tried to "fix" the eyes.

- The setting. If they are in a coffin, well, obviously. But if they are tucked into a bed with pillows propping them up, look for a lack of muscle tension in the neck.

- The presence of flowers. Often, a single flower held in the hand or a heavy garland was a signal of death.

Don't assume a "blank stare" means they're dead. Victorian photography required staying still for a long time. People got bored. People got tired. Most "creepy" Victorians were just trying to hold a pose while a guy with a giant box told them not to blink for sixty seconds.

📖 Related: The Long Haired Russian Cat Explained: Why the Siberian is Basically a Living Legend

The end of an era

By the early 1900s, this started to fade. Why? Partly because photography became cheap. People finally had photos of their kids while they were alive. They didn't need to wait for the end. Also, the funeral industry changed. Death moved out of the home and into the "funeral parlor." The "living room" (which used to be called the parlor) was renamed specifically to distance it from the "death room."

Modern people look at post mortem Victorian era photos and see something dark. But if you look closer, you see a father’s hand resting on the shoulder of a son he’s about to bury. You see a mother who refused to let her baby be forgotten. It’s not a ghost story. It’s a love story.

What to do if you find an old photo

If you've inherited an old family album and suspect you have a post mortem image, don't freak out. Treat it with the respect you'd give any family heirloom. These images are primary historical documents.

- Handle with care: Use cotton gloves. The oils on your skin can ruin 19th-century silver-based prints.

- Don't use tape: Never try to "fix" a tear with Scotch tape. It’ll eat the paper over time.

- Research the studio: Look at the back of the card (the carte de visite). The photographer’s name and location can help you date the photo to within a few years.

- Consult an archivist: If you think you have a rare daguerreotype, reach out to a local historical society. They can help you verify if it's a true post mortem or just a very grumpy living Victorian.

Understanding this niche of history helps us realize that our ancestors weren't "weird"—they were just trying to cope with the same grief we feel today, using the tools they had at the time. When you look at a post mortem photo, you aren't looking at a horror movie prop. You're looking at a person's final, silent goodbye.

Next Steps for History Enthusiasts:

Research the Thanatos Archive, which is one of the most comprehensive digital collections of early mourning photography. You can also look into the work of Dr. Stanley Burns, whose book Sleeping Beauty is the definitive (though very heavy) text on this subject. If you're interested in the broader culture of the time, visit a local Victorian-era cemetery and look for "broken column" headstones—they were the physical version of these photos, symbolizing a life cut short.